The Fortress of Favoritism

NOTE #1: This is the third post in a three-part mega-series. Be sure you’ve read Part 1 and Part 2.

NOTE #2: This three-part mega-series is itself a small part of a weekly journey I’m currently on with thousands of other podcasters to understand one question: What does it take to create someone’s favorite podcast?

Every Friday, a new idea shared via email that can push us one step ahead (with a bonus story/video via email only). These ideas will develop one coherent system we can all use to make someone’s favorite podcast, plus we’ll announce a few sessions of an interactive, online, cohort-based workshop.

Subscribe to join creative folks from Red Bull, Adobe, Shopify, the BBC, Mailchimp, and thousands of small businesses and entrepreneurs at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite.

![]()

What’s the best pizza in the world?

(I know we’ve addressed some really big questions in this three-part series, but this is obviously the most important.)

What’s the best pizza in the world? Really think about your answer. Seriously. Imagine a friend just texted you: What’s the best pizza in the world? GO! 🍕🍕🍕

I’ll give you a moment to think about it.

…

Got an answer? Great! You’re wrong.

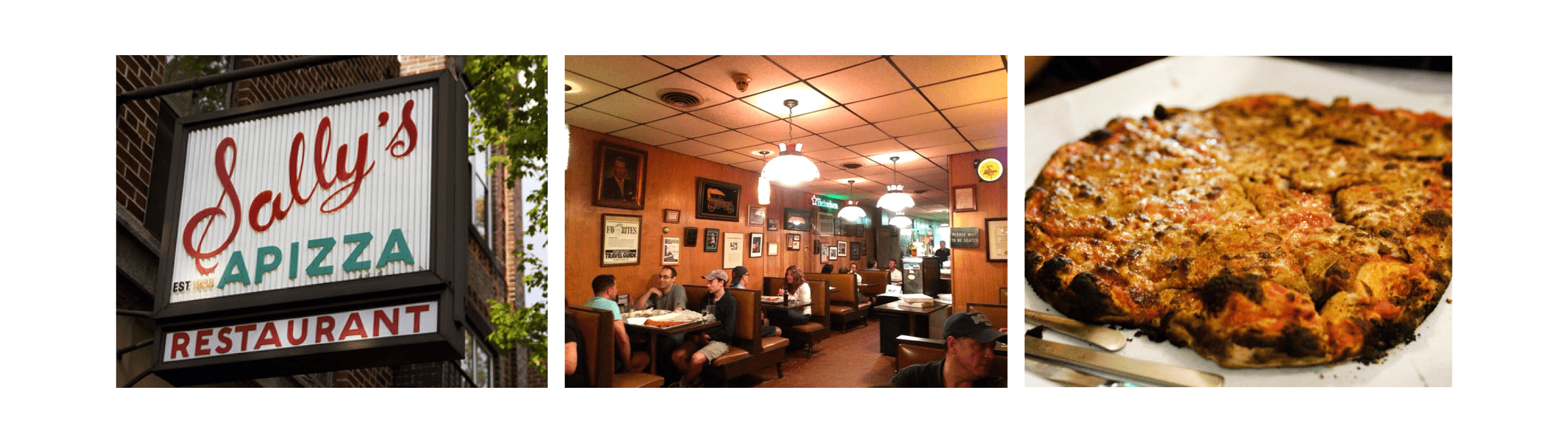

Yes, really. Because the one and only correct answer is Sally’s Apizza in New Haven, Connecticut, USA. Sally’s is the best pizza in the world.

I know this because I’ve eaten there dozens of times. My family has taken me there since I was a kid, and I will take my daughter there too. As a family, we know pizza. We make it in ovens and on grills. We eat it every which way you can eat it (though always with our mouths; the Great Pizz-ear Experiment of 1998 notwithstanding).

Personally, I’ve also eaten pizza in some alleged epicenters of quality pies, like New York, Chicago, and several places in Italy. I’ve had the new-agey stuff, the classic stuff, even the frozen and delivery stuff. It doesn’t matter. Neither does your answer. Unless you said Sally’s.

Because Sally’s is the best pizza in the world.

Sally’s Apizza in New Haven, also referred to as the best pizza in the world by people who know things. Like pizza. And which is the best.

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” you might be thinking. “Easy, pal. You’re way outta line here. The best pizza is definitely Joe’s Pizza, this little spot near my house.”

Or maybe you thought, “It’s La Gatta Mangiona. That’s in Rome. Ever heard of it? It’s a city. IN ITALY.”

Or perhaps, “It’s Regina’s, bro.”

“It’s SottoCasa!”

“Norma’s is the best!”

“Domino’s!”

But here’s the thing: Your answer is incorrect.

Also?

Your answer is correct.

…

At this point, your left eye may be twitching slightly. How can something be both correct and incorrect at the same time? That’s a real mind-bruiser, and so naturally, we’re gonna fling ourselves down to the mat and wrestle with this one awhile. It turns out that understanding what the heck I’m talking about is a crucial piece to answering our main question fueling this journey together: What would it take for you to make your audience’s favorite podcast?

Oh, and by the way: I know I said any answer might be correct. I need to amend that: Any answer might be correct … except Domino’s.

Domino’s is never the answer.

(It doesn’t matter what the question is.)

![]()

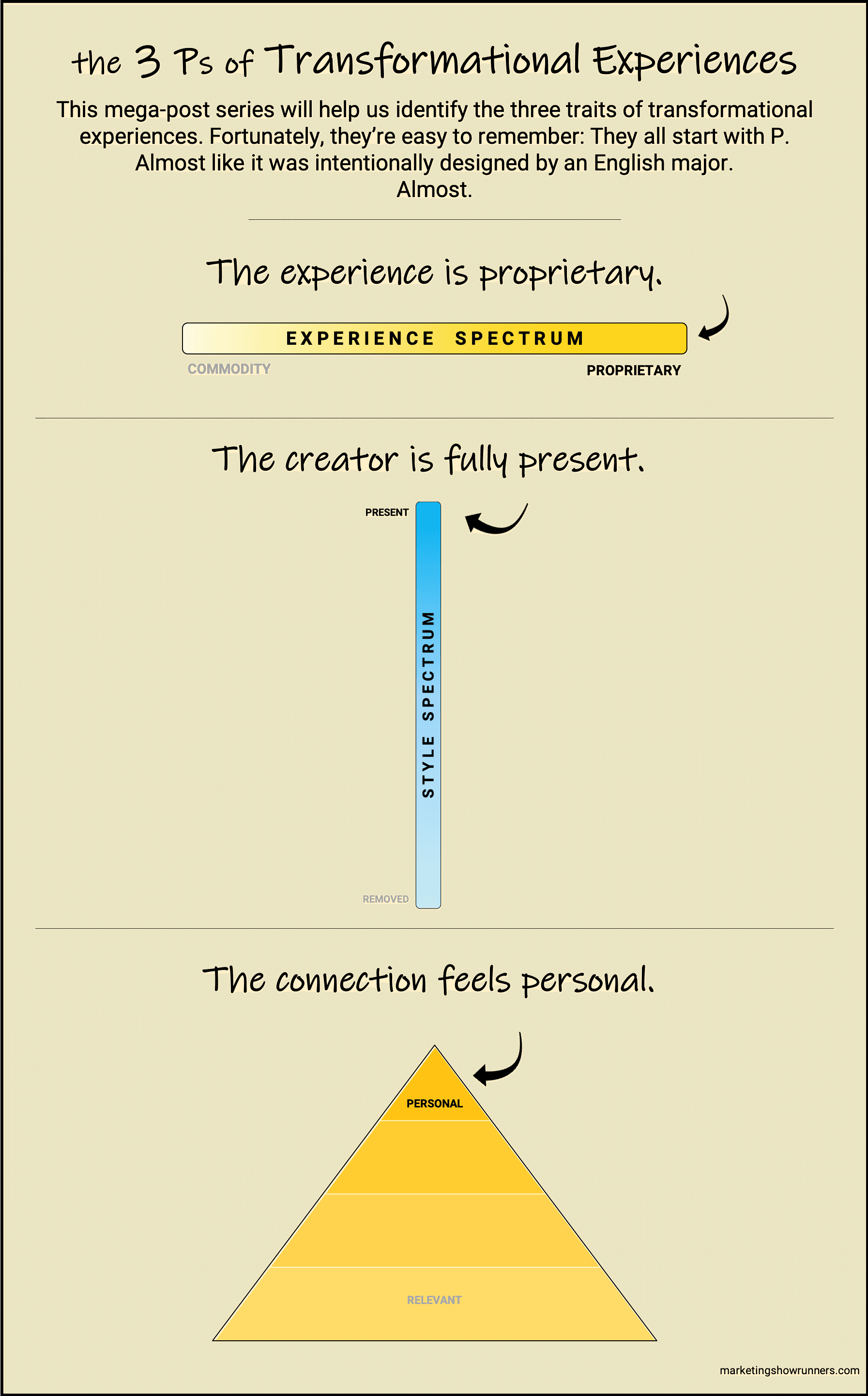

Welcome to Part 3 of our three-part mega-post series. Each of these posts explores one big question that supports our main goal of making someone’s favorite show. Those big questions again:

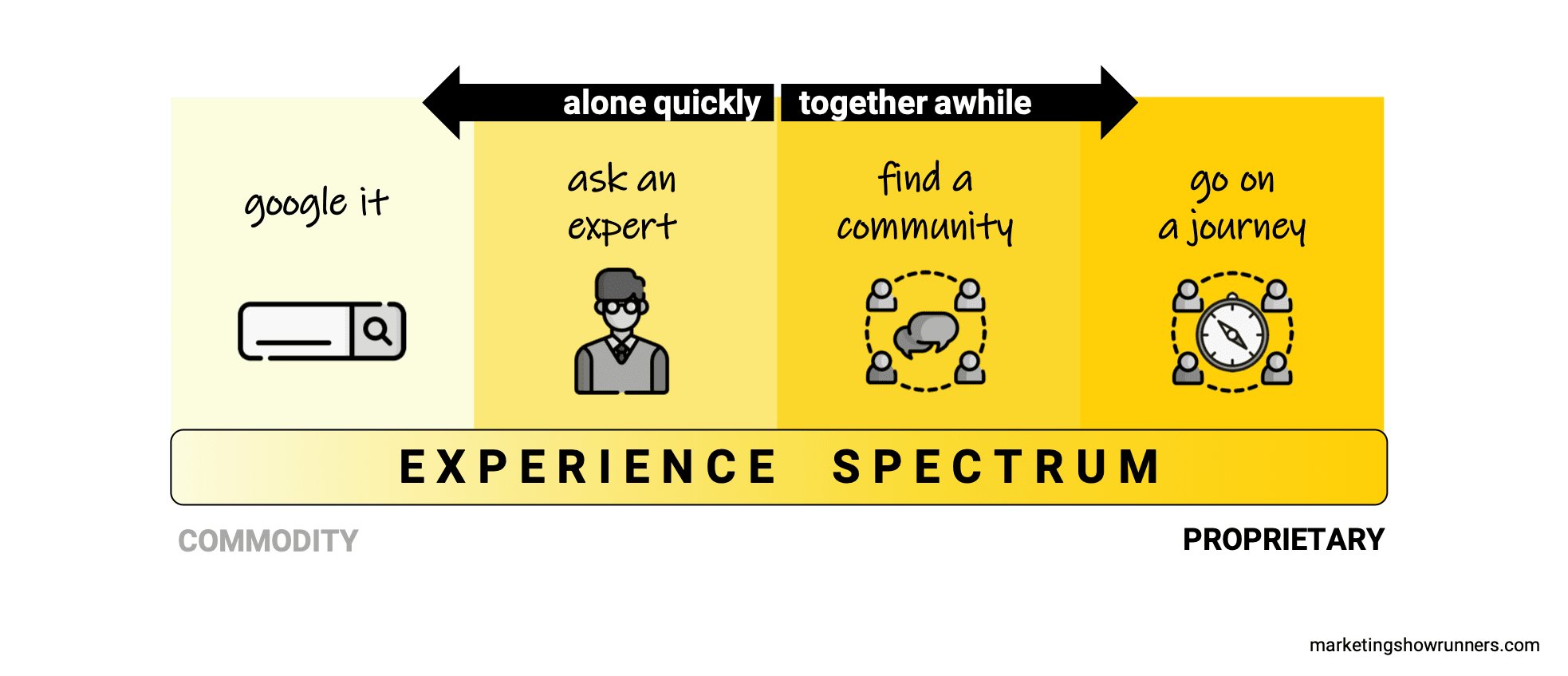

1) How do others experience our shows?

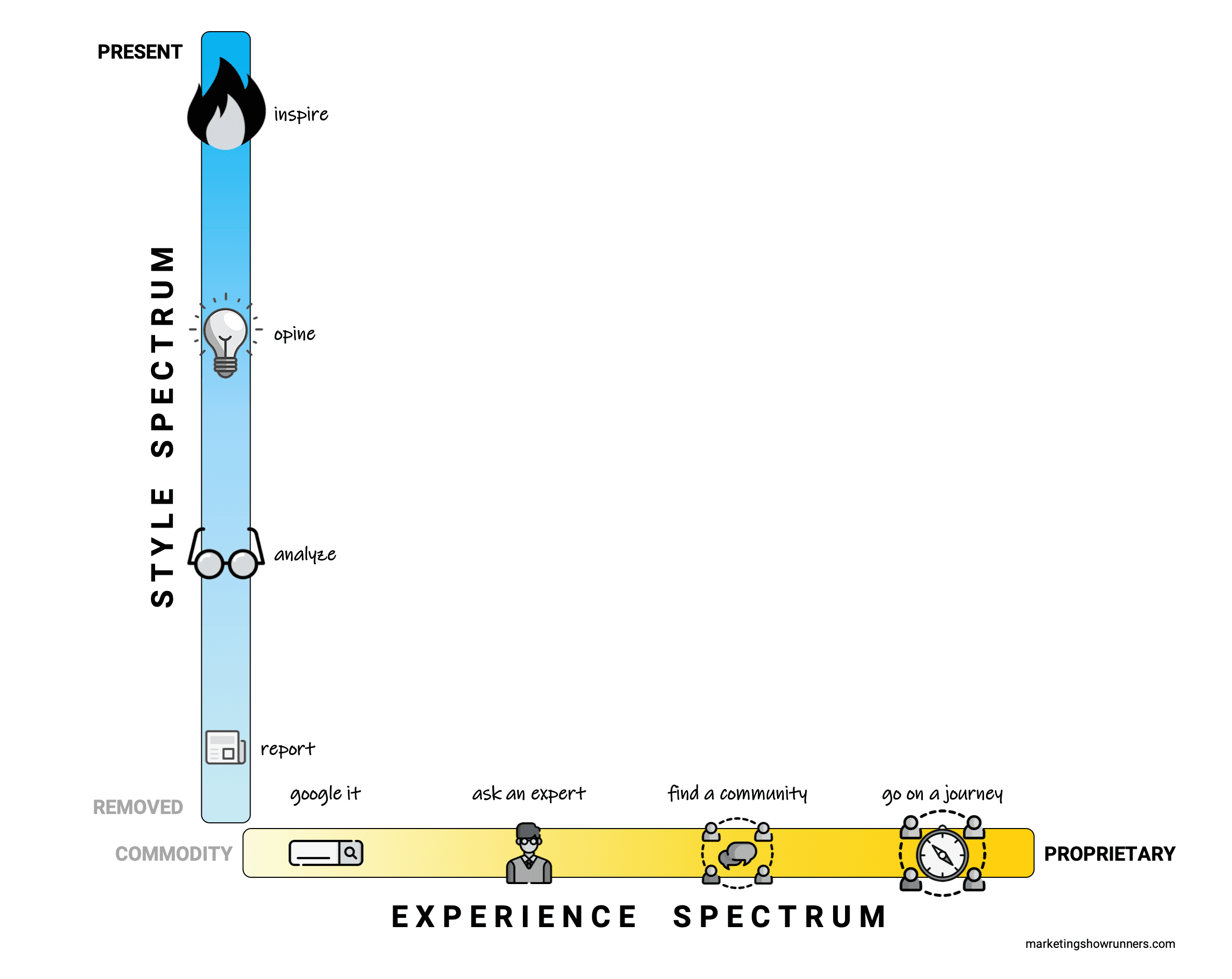

(Answer + tool to use: The Experience Spectrum)

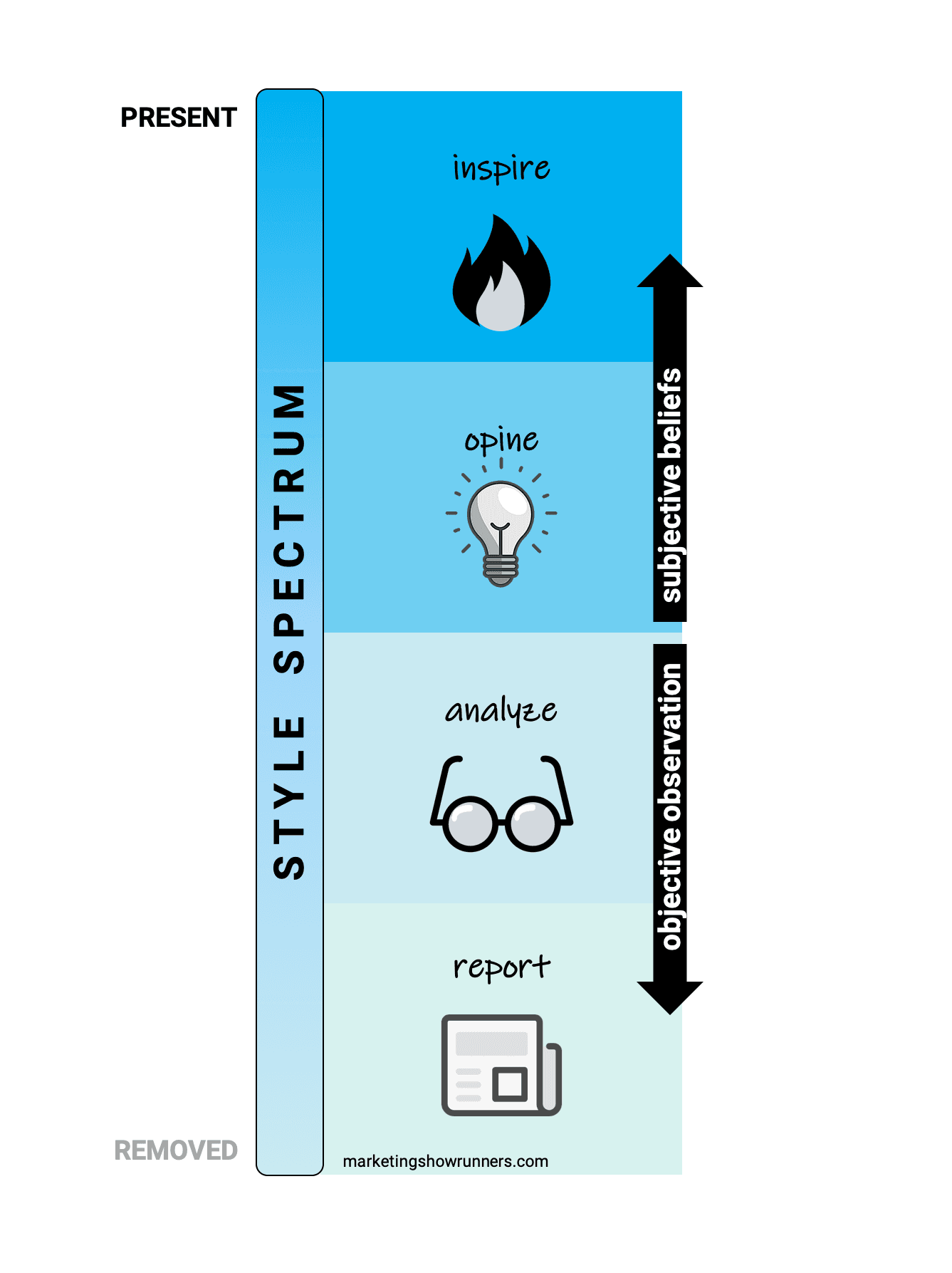

2) How do we personally influence that experience?

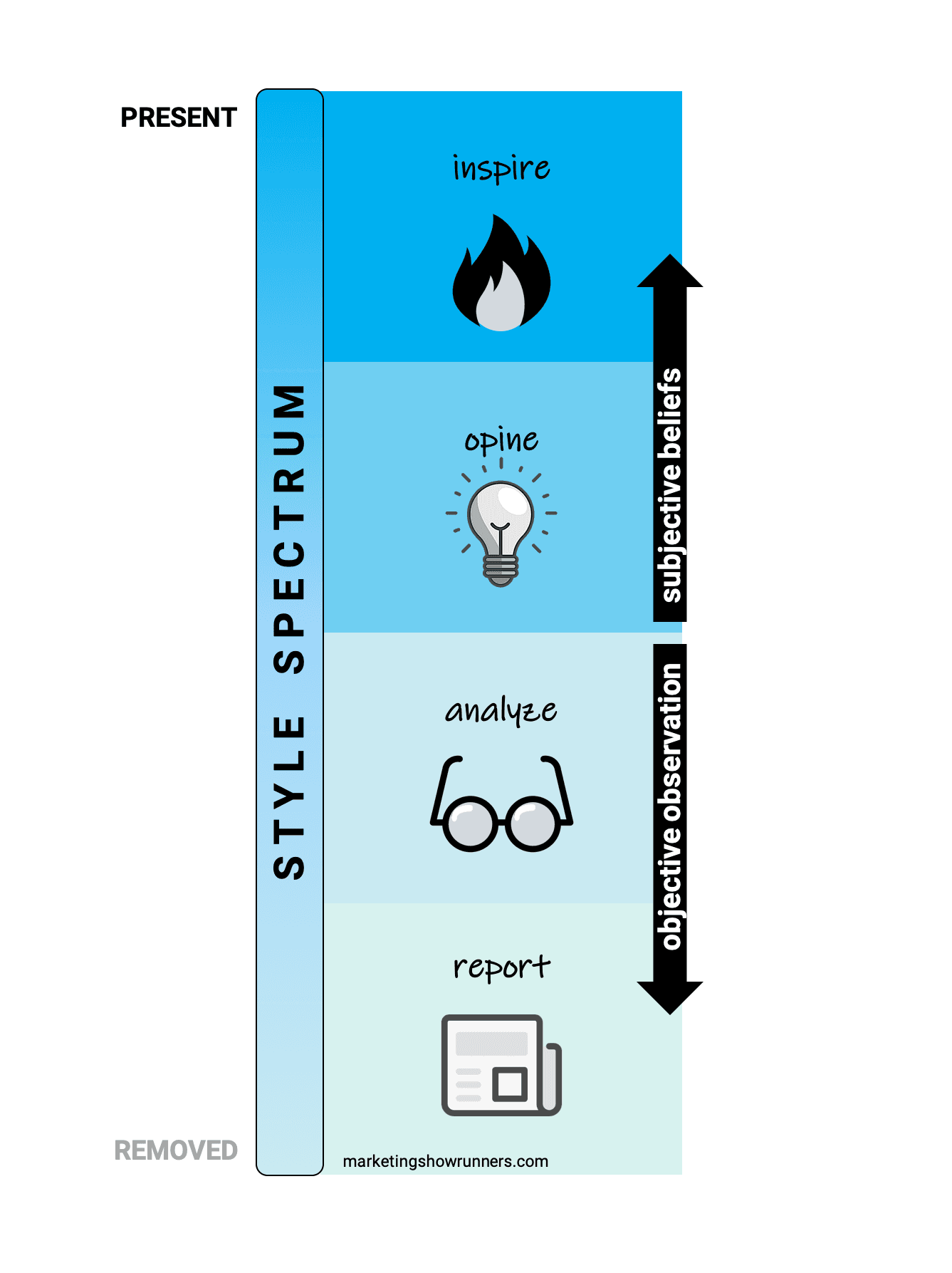

(Answer + tool to use: The Style Spectrum)

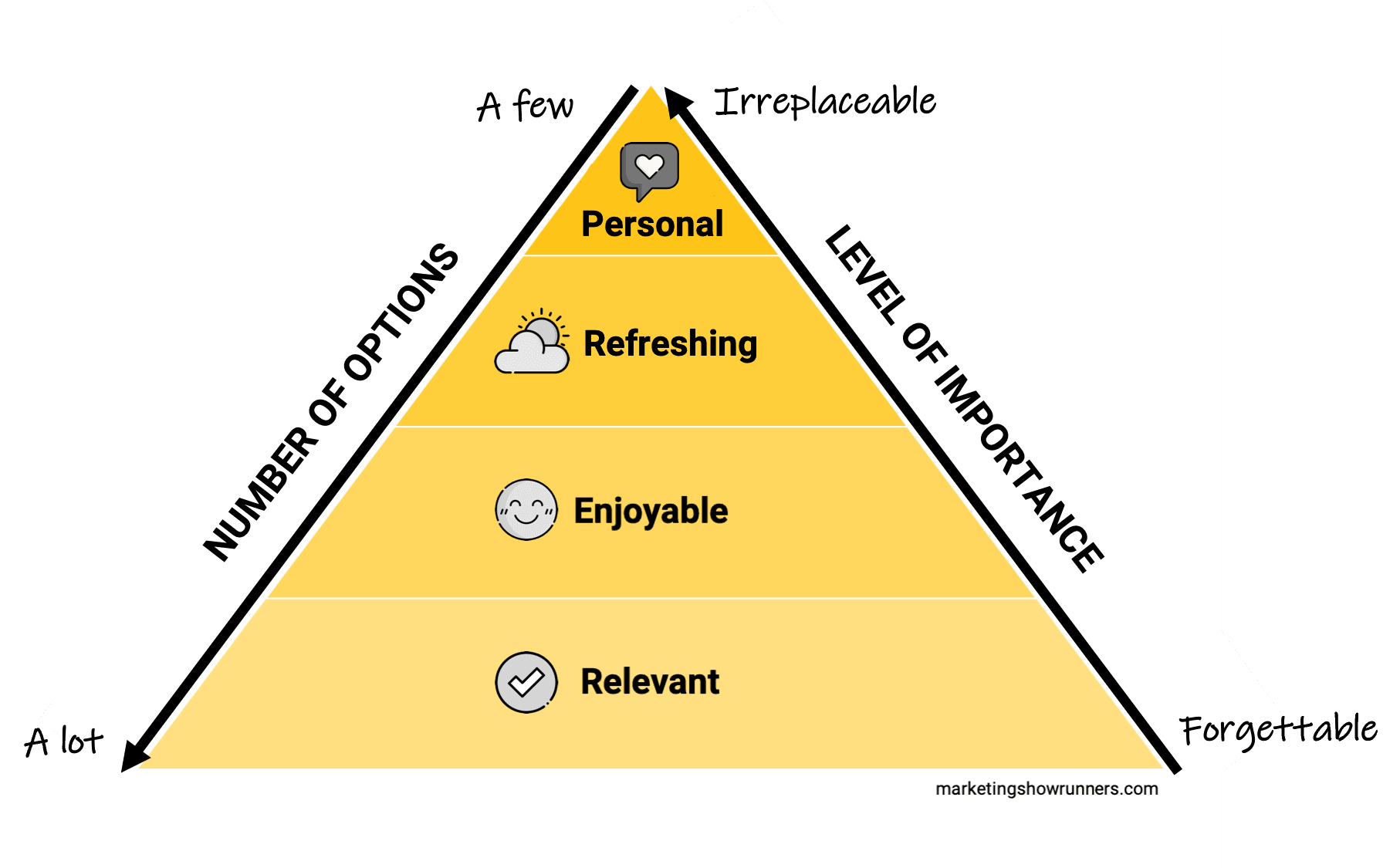

3) How do the Experience Spectrum and the Style Spectrum combine to affect how others feel about the show and about us? In other words, how does our work cause someone to declare, “That’s my favorite show”?

(Answer + tool to use: coming today.)

If you missed Part 1 or 2, please go back and read them here and here. Without those tools, this post won’t make a ton of sense.

As a reminder, the three questions above are our attempt to re-think how we approach our shows entirely. In our work, we don’t step back and re-think things often enough. We lose sight of first principles and coast on conventional wisdom. It’s just so easy to do so. But that’s kinda like embarking on an adventure and only knowing how to follow directions drawn on a map. By identifying first principles and rebuilding our approach from the ground up, we start to use something more valuable and powerful than directions on a map: our ability to explore. We aren’t trying to be great direction-followers. We’re trying to be great navigators.

So far, we’ve built a couple useful tools to help us re-think our approach and thus navigate the terrain ahead.

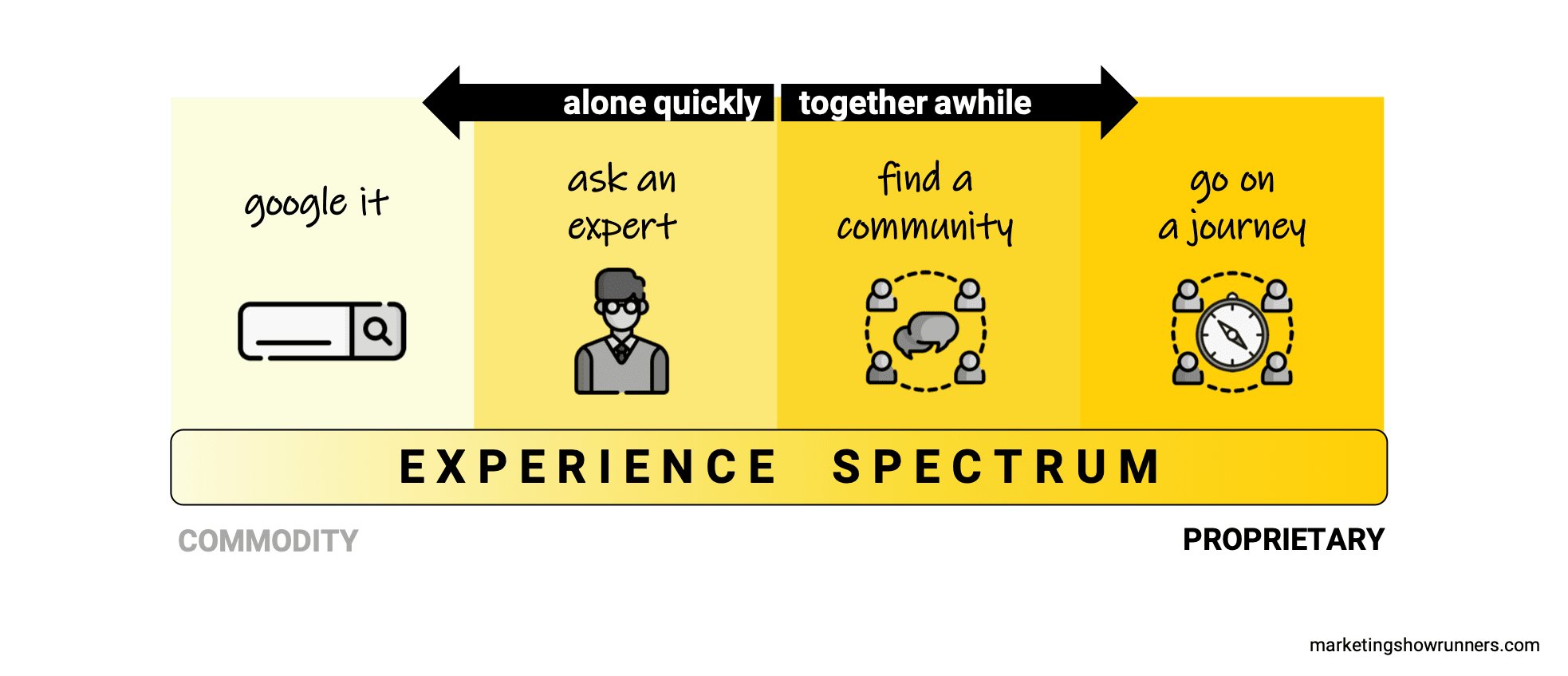

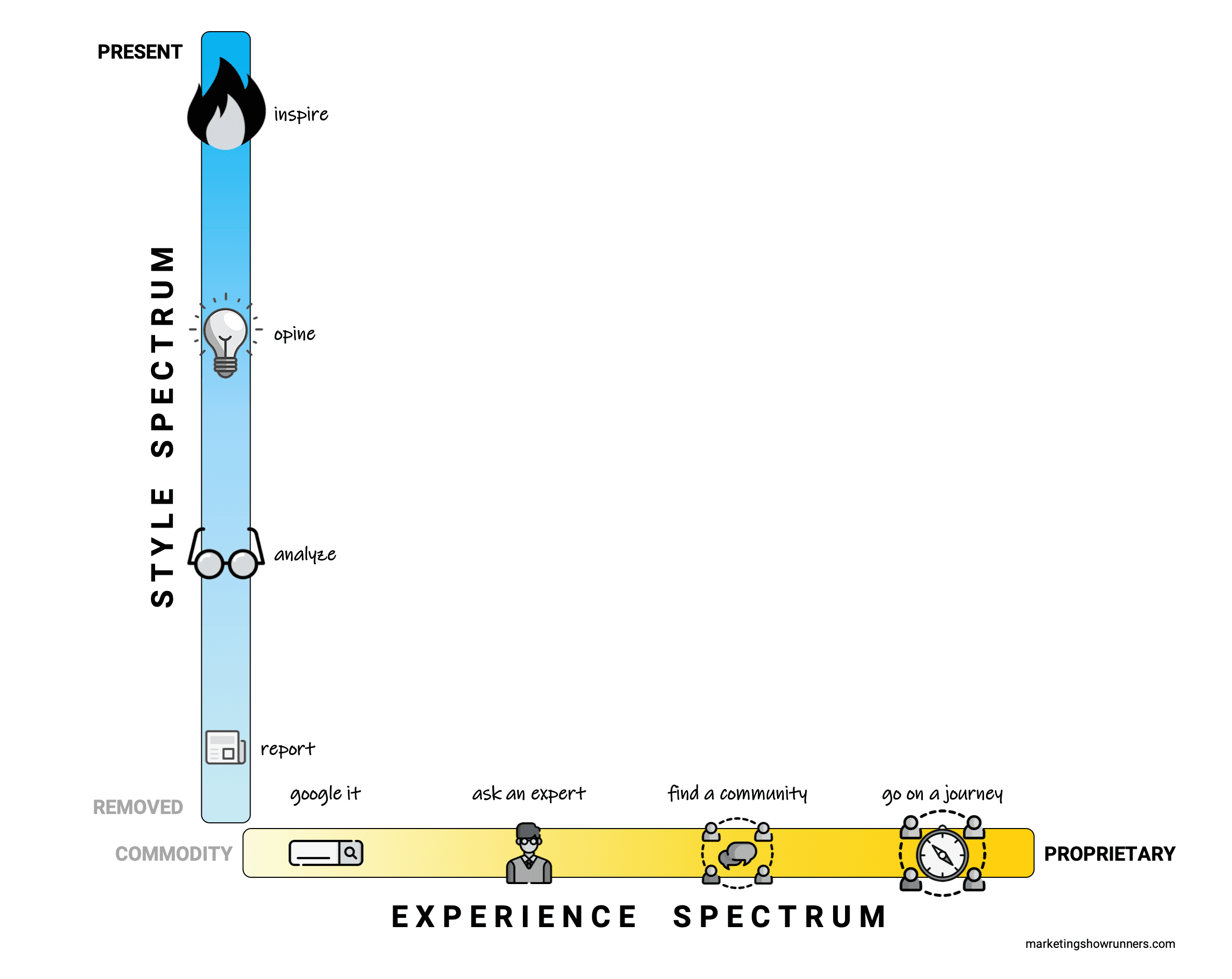

In Part 1, we built the Experience Spectrum, answering Big Question #1: How do others experience our shows? We can plot them along this spectrum.

In Part 2, we built the Style Spectrum, answering Big Question #2: How do we personally influence that experience? We can plot our own involvement in styling the experience along this spectrum:

By the end of Part 2, we put the two spectra together and also agreed that the word “spectra” is awesome and underused and deserves a million more mentions throughout this post. (You’re welcome, word nerds.)

Our mission, should we choose to accept it: maximize both spectra (+5 points for awesome word-use).

Maximizing the Experience Spectrum evolves the content from commodities to proprietary experiences.

To understand why this matters and how this happens, read Part 1 if you haven’t yet.

Maximizing the Style Spectrum evolves our role in the work from being totally removed to being fully present.

To understand why this matters and how this happens, read Part 2.

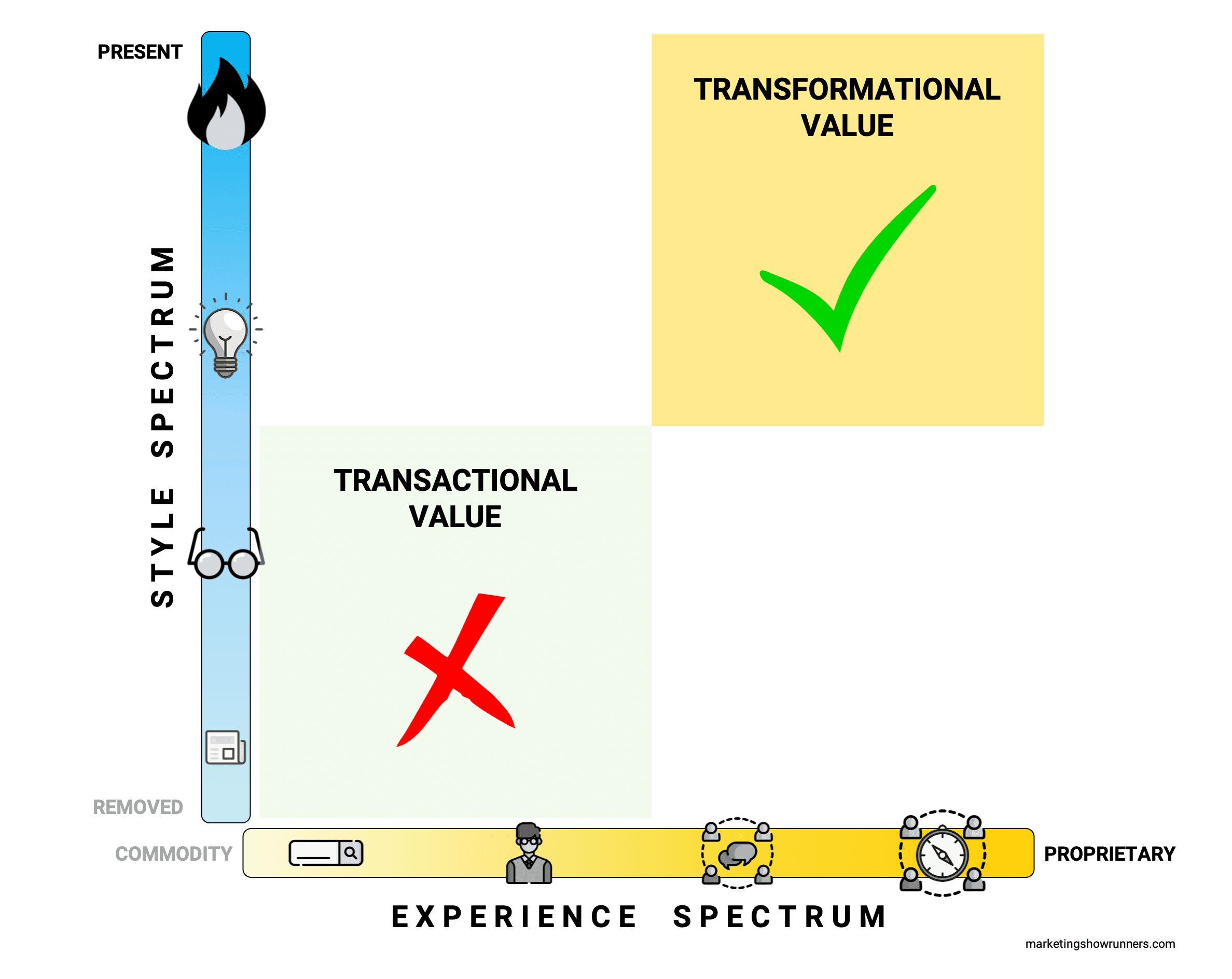

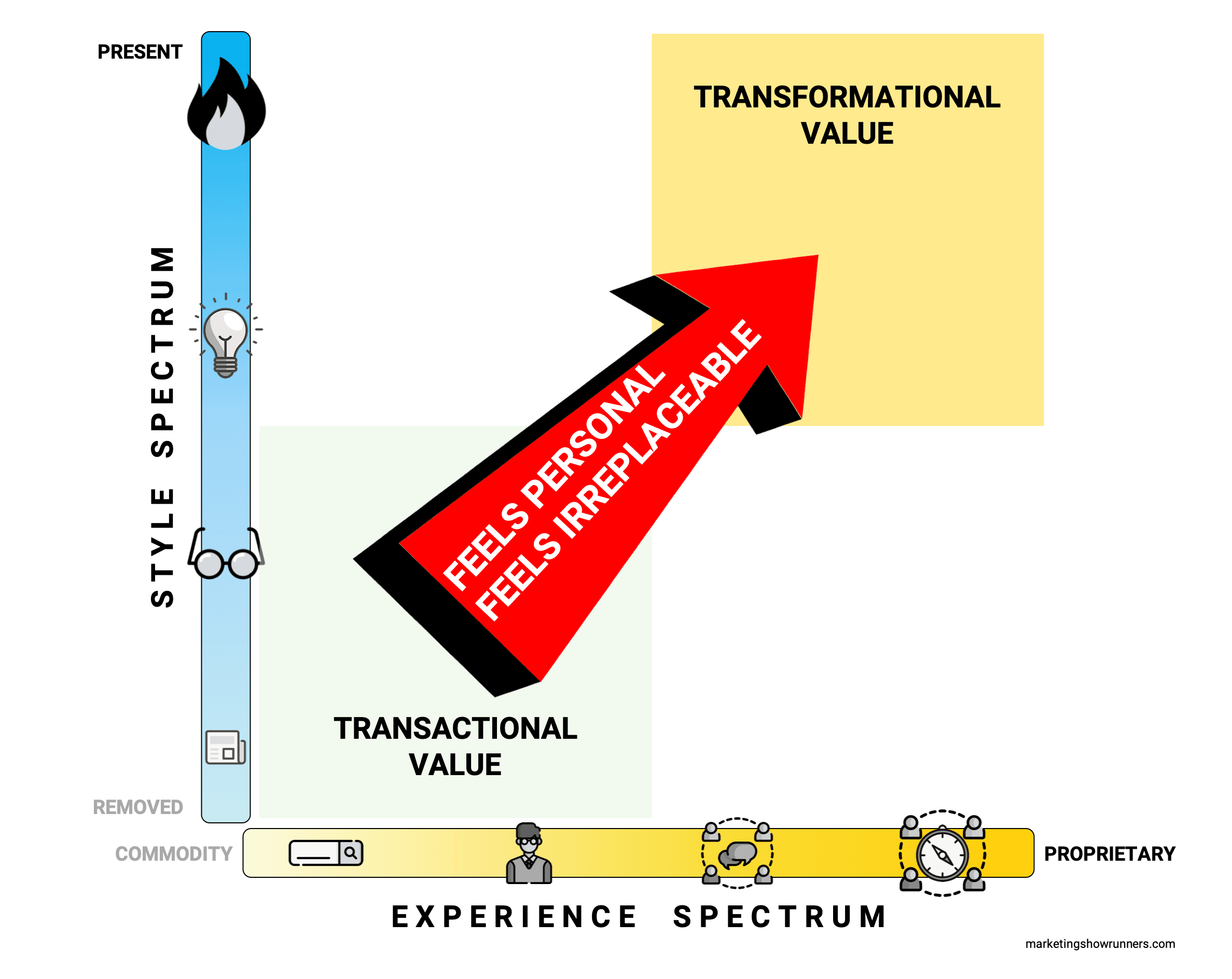

Maximizing both spectra evolves the value we provide others from transactional value to transformational value.

(I say “provide others” and not “provide our listeners” because when we successfully maximize both spectra, we not only increase the value of our work to our audiences but also to our teams, our organizations, our communities/industries, and to our own careers. It’s about having greater impact. To which group we serve? Answer: Yes.)

Let’s revisit the definitions of these two types of value as a quick refresher:

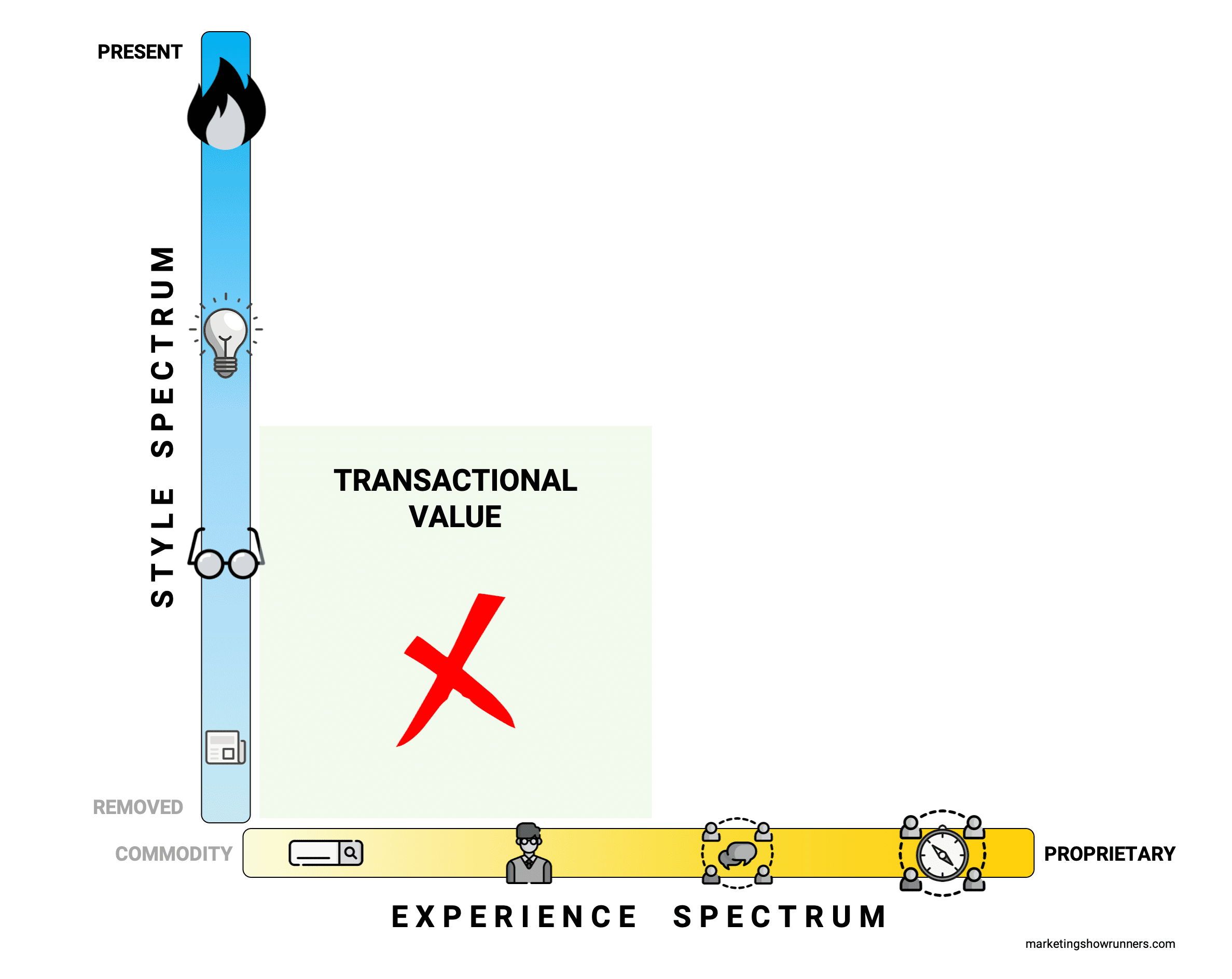

Transactional value is a type of education and/or entertainment people seek in reaction to a problem they’re trying to solve as quickly as possible.

Maybe they want to answer a question or learn a skill (transactional education), or maybe they’re looking for a temporary distraction (transactional entertainment). Transactional value is about acquiring something for a narrow purpose right now. The value is fleeting, the content is quickly and commonly found, and it’s not very memorable, nor defensible against competition.

Surveying the branded podcast community, you see all kinds of stereotypical shows that offer purely transactional value, such as…

🙋♂️ The We Also Have a Podcast Podcast: Here, the team is trend-hopping, doing a podcast because it’s become a thing (i.e. they put tactic over strategy). The show offers no specific premise or creative differentiation, and so the team is forced to describe the value with comparison-based adjectives, thus anchoring it to the competition: better, deeper, actually X, more Y, how Z really works, and so on. The shows you and I want to make can simply be described (“On this show, we do X”), and immediately, others should understand it’s valuable, rare, and different — no comparisons needed.

🍭 The Wheel of Fortune of Fortune 500s: These shows hype their gimmicks as the reason they’re supposedly valuable, or perhaps they overemphasize glossy production techniques or use clever names. It’s all to mask the hard truth: the value they’re offering is still transactional. It’s a commodity. It’s plain wheat, just with some sugar sprinkled on it. “We interview marketers from top brands, but they must spin this wheel to determine each question and topic!”

These gimmicky shows don’t fix the core problem but offer a balm for a bad experience instead. It’s like a doctor who goes, “This is gonna hurt but–HEYYYY how about a lollipop, Champ?!”

🚃 Amtrak Airlines: A short-lived type of show, Amtrak Airlines meets its demise after just a few episodes, because stakeholders thought the show would be good at doing stuff that the show is not good at doing. Podcasts are about depth, resonance, community, and accelerating trust and love. They aren’t great for fast growth and viral sharing, nor can they be valued using metrics better suited for direct marketing.

It’s kinda like YOU built an awesome train, but your boss wants the train to fly. But … that’s not … what trains … can do? Trains are great at doing very many train things, but they are pretty awful at flying. Better to embrace what you’re actually building and make the best damn version of that thing.

But no, “make it fly or it dies,” they say, and so Amtrak Airlines must approach its topics, guests, stories, and marketing the same way: pander to the status quo. Whatever the largest possible group in your niche is already searching for and thinking about, just do that. Forget any real change or impact. Forget making a difference or making things better. If it doesn’t currently have tons of demand, don’t do it — regardless of how transformational it might be.

As we’ve covered in Parts 1 and 2, and for obvious reasons given what you just read, our plan is to avoid creating these or any other types of transactional shows.

Let’s just put a big red “X” where we don’t want to be:

Transactional value is everywhere. It’s a commodity experience, and for content creators in the information age, information is the commodity. With very few exceptions, the source of curated facts and the source of expertise doesn’t matter. “What is…” and “what was…” and when, and where, and how-to — it’s all rather indefensible stuff for us to create. White label the content offering such transactional value, and you’d be hard-pressed to identify who created it — nor does the audience much care. “Is that the thing it promised it would be? Good enough for me. I’ll take it.” End of transaction.

To make someone’s favorite show, we’ve sworn off transactional value in favor of something that gives us a better chance at succeeding: transformational value.

Transformational value is a type of education and/or entertainment which creates lasting change in others.

It’s a type of value which compounds. The more time you spend with the experience that delivers this kind of value, the deeper you realize this pool of value goes. The more you try to use the value in your life, the more valuable it becomes — like a compass, compared to a map with a single set of directions on it.

Unlike a transaction, transformational value isn’t merely acquired in a single, quick moment, then you’re done experiencing it. The opposite is true: the experience itself is what transforms you. If I were to write a description or a summary of the most transformational music you’ve ever heard, it would do nothing compared to you actually hearing it. The same can be said of a book, or a relationship, or a meal, or, ideally, a show. You can’t distill it down to a few bullets so you can just transact your way to the same benefits. Transformational value is delivered in journeys — of discovery, of story, of travel, and so forth. Create such a show, and it’s a proprietary experience, sitting all the way to the right on the Experience Spectrum. And because this kind of experience requires you, the creator, to offer worthy points-of-view and real inspiration, you must bring your full self to the work, thus maximizing the Style Spectrum.

So let’s put a bright green check mark where we most want our shows to be:

Don’t pander to people. Make them better. Improve them. Show them what they longed to see but didn’t realize it, didn’t know to google it or ask the expert for it.

Don’t gauge where everyone is already going and then say, “Oh, yes, right, we have that, we say that, we are that, right this way.” That’s how you fall in line with other commodities. That’s how you transact the world instead of transform it. (For those reading this who are totally fine transacting the world, kindly exit this post. You will find no value the rest of the way. High fives, handshakes, and hugs to you … but we are not building something meant for you.)

Provide something better than your audience knew to ask for in the first place. Maybe there’s no proof of the demand right now, but that might be the point. Provide real inspiration to change them and change the status quo for the better. Craft a proprietary journey, and bring your full self to the work.

Focus on making a transformational experience. No more transactional shows. No more commodity content.

Please.

![]()

The differences between transactional value and transformational value can be difficult to describe but obvious when experienced, so I wanted to take one more moment to review the concepts through two different analogies.

Analogy #1: If “value” was like a software product.

Transactional value is like a point-solution. It does the one thing well, and nothing else. There are lots of similar point-solutions that all do that one thing — like, say, an app that lets users schedule and publish tweets.

Transformational value isn’t like a point-solution in this analogy. It’s like a software platform. It’s an all-in-one place to do a whole bunch of important stuff … which, sure, probably includes the ability to schedule and publish tweets. The platform also proves rather useful when you encounter other things you’d like to do that the software developers didn’t have in mind when they built the product. Those things plug right into the platform via the API. That’s what makes it a platform, after all: lots and lots of stuff sits on top of it, like it’s the first principles of products.

Unlike a point-solution, a platform has compounding value and can fundamentally change how you operate.

Analogy #2: If “value” was like your ability to write.

Transactional value is like a series of videos teaching you better sentence structure. It’s really useful — for that one thing and nothing else. It’s essentially the point-solution of writing education.

Transformational value isn’t like a writing course in this analogy. It’s like a writing mentor. The writing mentor provides ongoing ideas, inspiration, and advice which, sure, might be about better sentence structure for a moment, but also focuses on stuff like holding yourself accountable, practicing your craft every day, and bringing better ideas to your writing; finding and fleshing out stories and sources; scoping the work, dealing with drafts and revisions; pricing your services and working with clients, and the mental and emotional grit needed to have a long and thriving creative career.

THAT would change you, not just answer a single question about sentence structure.

Our shows should feel more like platforms than point-solutions. They should be more like mentors than video courses.

In other words:

Transactional shows help the audience. Transformational shows CHANGE them.

There’s no denying that a point-solution app can be helpful, just like writing with better sentence structure can be helpful. But I’m reminded of that old adage: Give a man a fish, you’ll feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, you’ll feed him for a lifetime, which will then give you time to reevaluate whether you should quote an old adage which refers to all humans as “man” because, cmon, it’s 2020.

(That’s how the old adage goes, yes?)

By the way, when I talk about something “transformational,” I’m not implying your show must be overly dramatic or change them in ways that affect the entirety of their lives. Regardless of your industry niche or style, you can add value that changes them for the better. It doesn’t need to feel … grandiose. If you teach social media tactics, change how they approach those tactics. If you recap tech news or industry trends, change how they understand and interpret technology in their lives, or how they view and interact with their industry.

You can change how they craft podcasts or root for their favorite team. Change how they consume reality TV or read fantasy fiction. You can change something all-encompassing, like how they see society, culture, politics, or religion, or change something specific, like how they make coffee or play with their kids.

Whatever the case, whatever is relevant for your brand to address and explore, just remember what it is that we are here to do as showrunners, as creators, and as marketers:

Transactional shows help the audience. Transformational shows CHANGE them.

Now, I’m not the smartest person in the room. (Actually, I’ve worked from home for three years, so technically, I am — although you should see what my dog can do with a bone, a bed, and unlimited time to hide something I swore I gave him earlier today…)

So I’ll rephrase: I’m not the smartest person in most rooms, but I know I can’t simply tell you, “Hey, why not make something that transforms your audience?”

That’s why we’ve spent a ton of time developing the two spectra we’ve developed so far. It’s also why we need to create a new tool today. When combined, the three tools will create something every great navigator needs: a compass.

The rest of this post is divided into two sections:

Section 1: The Missing Piece. (Spoiler alert: This is where we have to talk about pizza again, so maybe grab a snack.)

Section 2: Completing the Compass. (Spoiler alert: This is a mini-section, but it’s also where I’ll probably definitely have another existential crisis about how long these posts are.)

Onward!

Section 1 of 2: The Missing Piece

Building a compass capable of navigating our shows and our creative aspirations towards a podcast that changes people sounds kinda … complex … so now feels like a good a time to re-introduce our helpful guide: a magic wand whose entire existence is to make complex ideas not so complex. A magic wand named Bob.

As many times as you appear in this series.

So “as many times as you appear in this series.”

…

…

Should we just pretend you didn’t try to rap?

So, as you can tell, Bob is kind of a weird dude — both as sentient creatures go and also as magic wands go. You see, he only grants two types of wishes. (Bob has what Liam Neeson might call “a very particular set of skills.”)

If I wave him with my right hand, he reveals a concept to help us understand what we most desire to understand. If I wave him with my left hand, he reveals an example to help illustrate that same thing. So far, in Parts 1 and 2, he helped us build the Experience Spectrum and the Style Spectrum.

(This will all seem just a little less bizarre if you’ve read Parts 1 and 2, so please do so if you haven’t.)

(The operative words being “just a little.”)

Let’s get Bob’s help to answer Big Question #3 in our three-pack of big questions guiding this mega-post series:

3) How do the Experience Spectrum and the Style Spectrum combine to affect how others feel about the show?

In other words, how can this all lead to someone declaring, “That’s my favorite show”?

Throughout our not-so-little adventure so far, I’ve used the word “favorite” without really giving it much thought. However, the more I dig into that concept, the more I realize we should probably define it. It might seem silly, given how freely we use the word in everyday life, but there are just too many misinterpretations of that word — or any word — to leave it to chance. Let’s start by understanding this concept of “favorite” a bit more.

I’ll just wave Bob with my right hand and see what he gives us. Here we go…

“Favorite” does not mean “great.”

Interesting start. Let’s figure this out.

This journey we’re on together is NOT a journey to make “great” shows — at least not if you define “great” like many of us do. Sometimes, we use the word “great” to mean “big.” It’s a widely-known show, or a show that’s highly-ranked on Apple Podcasts or according to various industry blogs, so that show is or must be great. Other times, we use “great” to talk about the content inside the show: “great stories, great reporting, great host, great guests, great sound design, great music, great cover art, great brand … great show!”

But “favorite” doesn’t mean “great” in any objective or comparative sense. It’s not a measure of how good something is at all. In fact, your favorite things might be something you freely admit aren’t all that good, in some academic sense. It’s why sometimes you sheepishly admit to your love of a certain artist or song or TV show: you know it’s not broadly considered to be among the best. It’s not big or highly ranked or praised by the critics who apparently know things. Why does that cause you to sheepishly admit it’s your favorite? Because you’re worried about what it says about you that you still like it. Or maybe you proudly declare something is your favorite because you enjoy what it says about you.

Our favorite things say something about us, about our sense of self and our place in the world. In other words:

Our favorite things are tied to our identities.

That’s one crucial fact we can use to better define “favorite,” as separate from “great.”

Taking one step further, we can now understand why sports fans can admit their favorite team isn’t the best team … or, if you’re like me and root for the New York Knicks, even a good team. Or a bad team. Or a horrible team.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say the Knicks are the worst team. They’re also my favorite team.

Let that sink in: Something I just freely admitted is the worst version of the overall cohort of things … is still my favorite.

(I told you when I introduced the Sally’s example at the top of this post that this is a mind-bruiser. We’re wrestling it now. It’s gonna be painful. Just like rooting for the Knicks.)

(I’m really sad to be a Knicks fan, you guys…)

So now we arrive here, adding #2:

1. Our favorite things are tied to our identities.

2. Our favorite things are still our favorites when objectively better options exist.

Said another way: Our favorite things feel personal (#1) and irreplaceable (#2). They’re tied to our identities, our sense of self, and what our likes or dislikes say to others about us. They’re also separated from objective decision-making. The fact that other similar or even better options exist has no bearing whatsoever on our relationship with our favorite things.

I might be sad if a great restaurant near my home closes. But if they ever closed one of my favorite restaurants, Sally’s Apizza in New Haven? I would be inconsolable. I would drop to my knees and shout to the heavens, admonishing every god and goddess ever named by humankind, as it rained down on me. (Oh, right: In this scenario, when I hear the news, I’d first trash my apartment and go sprinting out into the street crying before collapsing to my knees.)

Rational response to a pizza place closing, no? No! And that’s the point. Deciding what is your “favorite” thing is not a rational decision at all. It’s entirely subjective. It’s wholly dependent on the subject — the messy, unique, ever-changing, impossibly complex sack of emotions, topped with trillions of neurons firing and connecting and re-connecting constantly, also known as a single human.

(But, sure, definitely read that blog post offering 7 secrets to marketing to millennials.)

Our favorite things feel personal and irreplaceable. It has nothing to do with any objective ranking or set of traits or competitive cohort (i.e. being “great” in some objective sense) and everything to do with you and how you feel about the thing.

“Great” is a bit of a weak moat.

“Favorite” is a fortress.

So, thanks to our magic wand friend Bob, and two and one-third mega-posts about making someone’s favorite podcast, we’re now ready to build the final tool, a model we can add to our two spectra. This tool describes how others feel about the show. Let’s call it…

The Fortress of Favoritism

Before we start building the fortress and getting all silly with Superman references, I need to address a word that feels kinda icky: favoritism.

In society, when we use the term “favoritism,” it often has a negative connotation. Someone (correctly) points out the detriment of this decision-making style to someone else: You’re picking that person or thing despite the fact that other, objectively better options exist. You’re being extremely biased.

Well, for our purposes, I’d say to that concerned citizen: EXACTLY! That’s exactly what we want. Sure, we reject favoritism in the negative, nepotistic, socially and culturally damaging sense. But we absolutely, one-million-percent want our audiences to be irrationally biased in favor of our shows and our brands. We want them to pick us despite the fact that other, objectively better (or at least comparable) options very well may exist.

When someone points out that there’s objectively better pizza, or clothing, or basketball teams, or cities to visit, or software to buy, or accountants to call, or shows to download, the end consumer of that stuff should freely admit, “Yeah, that might be the case, friend-o, but THIS is still my favorite.”

We want that.

And that is wildly irrational of them to say and think and feel, because it’s wholly personal. Favorite doesn’t mean great. It doesn’t mean anything objective. Because it’s personal, it’s irreplaceable — even if replacements (even great replacements) exist.

Does your show feel personal to them? Does it feel irreplaceable?

There’s a popular question many software companies ask their users to determine if they’ve built something that has product/market fit: “How disappointed would you be if you could no longer use this product?” Users select one of three answers: Very disappointed; Somewhat disappointed; Not disappointed (it really isn’t that useful). The idea is to measure how irreplaceable the product is.

Likewise, we can frame our approach to making podcasts in the same way: Can they easily replace our show? How disappointed would they be if it went away?

“Great” shows are replaceable. I would be sad if the funniest podcast in my feed disappeared … for a moment. But then I’d go find another podcast which is also great at being funny. I’d be fine. But my favorite show? That show (Radiolab) would truly hurt to lose. It feels impossible to replace. Sure, part of the reason why is their audio, their content, the way it’s built — what it is. But mostly, it would hurt to lose and feel impossible to replace because of why I love it.

It’s personal.

When I think about Radiolab, I think about being in my 20s, finding my way through the marketing industry, hating that I’d left behind my desire to be a journalist and work in tech instead, after initially loving it. I was totally disillusioned by the short-sighted, hollow content and the people (some who were even well-meaning, nice people) who were totally fine publishing cheap or gimmicky stuff and gaming systems to drive results. I was at my wit’s end, ready to abandon the career path but unsure of what would come next, so I just started to accept that I would stay in marketing forever and just sort of … exist. I was about as uninspired and angry as I’ve ever felt. That’s when I found Radiolab, and it reignited my desire to tell meaningful, deep, complex stories.

It took me on a proprietary journey through their stories and sounds. It changed me. Because it’s transformational to me.

I also remember a few years after that, driving home from a New Years’ celebration at a ski house in Vermont, when I decided to play Radiolab’s episode about speed (the motion, not the drug). It was the third time I’d listened to that episode. We were cruising down a highway on a sunny day, but not just any sunny day. It was one of those uniquely winter sunny days, when the sun is low and kinda in your eyes, forcing you to squint your way forward. The light was gleaming off the untouched white snow on either side of the highway, but the roads, I remember, were totally dry. My wife was sitting to my right in the passenger seat, and a guy I went to college with was in the back seat. The thing is, I didn’t really know him. We just had a mutual friend — the woman whose ski house we’d visited — and he happened to live near enough to me and my wife that I offered him a ride home. His name is Willis. I haven’t talked to him since. I do remember it was his first Radiolab episode, and I take great joy in sharing that with him, as well as remembering everything that happened both in that car ride AND all weekend long at that ski house.

Now I’m thinking about my friend whose house it was. She lives in San Francisco now. We’re losing touch. She has a beautiful new baby boy. I should call her. Maybe we could bond again over being parents of young kids, or reminisce about the many ski trips we had.

Alllll of that is why Radiolab is my favorite show.

Your favorite thing might enter your life because it was recommended to you by someone who already feels a personal connection to it, or because it’s objectively “great” and therefore publicly praised. But the show only lasts in your life because it becomes personal. In the process, it becomes irreplaceable.

This is where we need to take a leap of faith, you and I, because I don’t know that I can reason this one out: When we strive to make their favorite show, we shouldn’t strive to make the “best” show in our category. Instead, we should attempt to make a show capable of becoming personal. That type of show can’t be replaced. To a listener, it’s in a category of one.

“Favorite” doesn’t mean “great.” It means something far more important:

Favorite: Their personal, preferred pick for a specific purpose.

It is entirely possible to fall anywhere on this matrix, and be a “good” show — or even a great one.

For instance, a show in the lower left is purely commodified. I am not calling commodified shows bad. It’s possible to do a smart, even enjoyable news roundup. As we discussed in Part 2, the lower tiers of the Style Spectrum are like the foundation and the scaffolding of the house we’re building — important pieces to be sure, but also insufficient to finish the job of a builder.

These spectra shouldn’t be used to judge good or bad. They should be used to judge “capable of being their favorite” versus “not capable of being their favorite.” And since we now have an idea for what favorite means, we can rephrase that a bit to clarify:

Our tools, once combined, should help us see whether our show is personal and irreplaceable to our audience.

Transactional shows are not. Transformational shows are. The first might be helpful or even enjoyable. They might even be “great.” But the second category is uniquely capable of changing the people we aim to serve.

Let’s go back to an example, waving Bob in my left hand a moment, so we can illustrate the differences.

Our marketing brand’s most basic, most commodified podcast was called Marketing Trends. It’s a show about marketing trends.

You can absolutely make this show enjoyable, even if all you do is simply curate and share industry news from last week. (For instance, maybe you use clever and funny language to describe the news. “Mailchimp’s new banana is a feature that helps marketers do XYZ…”

(No, Jay’s brain, I said “clever and funny,” not “lame and predictable.”)

The problem is, because curated facts about the marketing industry is such commodified, google-able information (i.e. this show is extremely transactional in value), two things happen, neither of which are ideal:

1. The show leaves it all up to the host. The analogy I used in Part 2 is that a show’s construct (the show’s overall premise and the episode’s specific format) are like building yourself your very own Iron Man suit. You might be smart and charming like Tony Stark, but inside your Iron Man suit you become a friggin’ podcasting superhero. The construct of the show should maximize your abilities and give you new ones you didn’t previously possess. So if you plan on making a commodity show that is still “great” (in this case, enjoyable and funny industry news), it’s like telling Tony Stark, “Hey, see those space aliens and superhumans over there battling it out? Just go be super charming. You’ll figure it out. What? “Supersuit”? Ha, no, no, that takes too much planning and too many resources. You’re fine!”

Then Tony waltzes out into the battle and the Incredible Hulk trips over a space alien and accidentally squashes him.

Not ideal.

There’s another issue with trying to make a “great commodity.”

2. The more listeners listen, the more they’ll demand you evolve the show towards transformational value. Over time, the show starts to do its job. In the case of a news roundup, that means informing listeners with the facts. The more listeners consume those facts (or whatever it is the commodity show offers), the more they start to try and move further on the spectra … without you involved.

When our example show Marketing Trends does a great job sharing curated trends and updates from marketing’s last week, over time, the listeners become better informed, and thus want something more. They begin to gaze right on the Experience Spectrum.

Maybe they start with Marketing Trends, which is all the way on the left: a show offering google-able information. Then listeners might realize there’s a newsletter that shares similar content to those episodes from a different brand. Maybe some of their listening time then gets replaced with that competitor’s emails — a faster way to acquire the commodity info each brand offers. Next, one step to the right along the Experience Spectrum, the listeners might seek out experts to comment and analyze and give the broader context to the stuff Marketing Trends shares. Since that show doesn’t proactively provide much analysis (preferring to just present the curated news or trends unfiltered), listeners might just switch to another podcast entirely — one which presents the latest news and interprets it. Bye-bye, Marketing Trends.

Over time, these listeners start to sense a larger community of like-minded listeners and marketers exists, so now they crave a tribe and seek connection around the show … which then might turn into a journey to change how they all see and practice their marketing.

Now I’d ask you: If all of this stuff is going to be something the audience craves over time, shouldn’t YOU provide each experience as they evolve? Shouldn’t YOU be that expert? Shouldn’t YOU build that community, and take them on an inspirational journey?

The more a commodity show succeeds in serving listeners, the more it becomes irrelevant. The longer a transactional show lasts, the more its forced to evolve into a transformational journey — or it dies. Listeners will crave each new phase of the Experience Spectrum. They can find it without you … or you can provide it.

Thus, we’re better off taking all that energy and all those resources we’d normally spend making a commodity feel more enjoyable, and just use them to make something that isn’t a commodity at all, right from the start. Listeners are going to want that anyway.

Don’t make a transactional show. Start by trying to make something that can feel more personal and become irreplaceable. Start by aiming to change your audience for the better.

Start by trying to be their favorite show.

And look, I know none of this is rational. We can chase our tails all day trying to reason our way out. I can beat this dough until it becomes too thin for even Sally’s to make something delicious out of it. (Who am I kidding? It would be unbelievable. They do the Lord’s work.)

🍕🍕🍕

Let’s revisit the question from all the way back at the beginning of this post:

What’s the best pizza in the world?

Your answer was incorrect. The answer is Sally’s. Also? Your answer was correct. It’s whatever you said. How can that be true? Because when we typically talk about the quality of something, we aren’t usually describing the academic, objective version of words like “good” or “great” or “best in the world.” We’re usually talking about something implied — the same something that prompts a person to excitedly refer their favorite things to friends: What’s your personal, preferred pick, for this specific purpose?

I might say, “What’s the best pizza in the world?” What you probably hear is, “What’s your personal, preferred pick for pizza?”

Your answer probably wasn’t, “Well, there are 16 different global rankings for pizzas used by various associations, each with their own scoring system, and so my answer is the average of all 16, or else you and I should discuss which of these systems we should consider our single-source of truth. Or did you prefer to use a magazine ranking? I count 79 publications in the United States which–”

Nope.

What’s the best pizza in the world? Well, my personal preferred pick for pizza is Sally’s. My favorite is Sally’s.

Sally’s is the best pizza in the world.

This is the truth … according to me, and several thousand other loyalists. You might have a different truth here. Both truths are equally true, because both are dependent on the person saying them. It’s subjective.

That’s how your answer can be both correct and incorrect at the very same time.

Are there objectively better pizzas than my pick or yours?

Is your competitor’s podcast great?

Is your show the #1-ranked in the category?

Maybe … perhaps … and who the hell cares? That’s not the point of any of this. (“We’re the leading podcast in the XYZ Industry.” Pffft, I say, and again I say, Pffft. That’s missing the point entirely.)

Does your show feel personal and irreplaceable to your audience?

Now you’re on the right path…

So now that we’ve addressed the icky-sounding word “favoritism” and better-defined what we even mean by “favorite,” let’s build our third tool, The Fortress of Favoritism. The key thing to remember as we do so is that this diagram answers the third big question in our journey: How do others feel towards your show?

The Style Spectrum describes how we’re involved in the crafting of the experience. The Experience Spectrum describes how the audience consumes the experience. The Fortress of Favoritism describes how the audience then feels as a result of those two things. It explains the big red arrow in more detail:

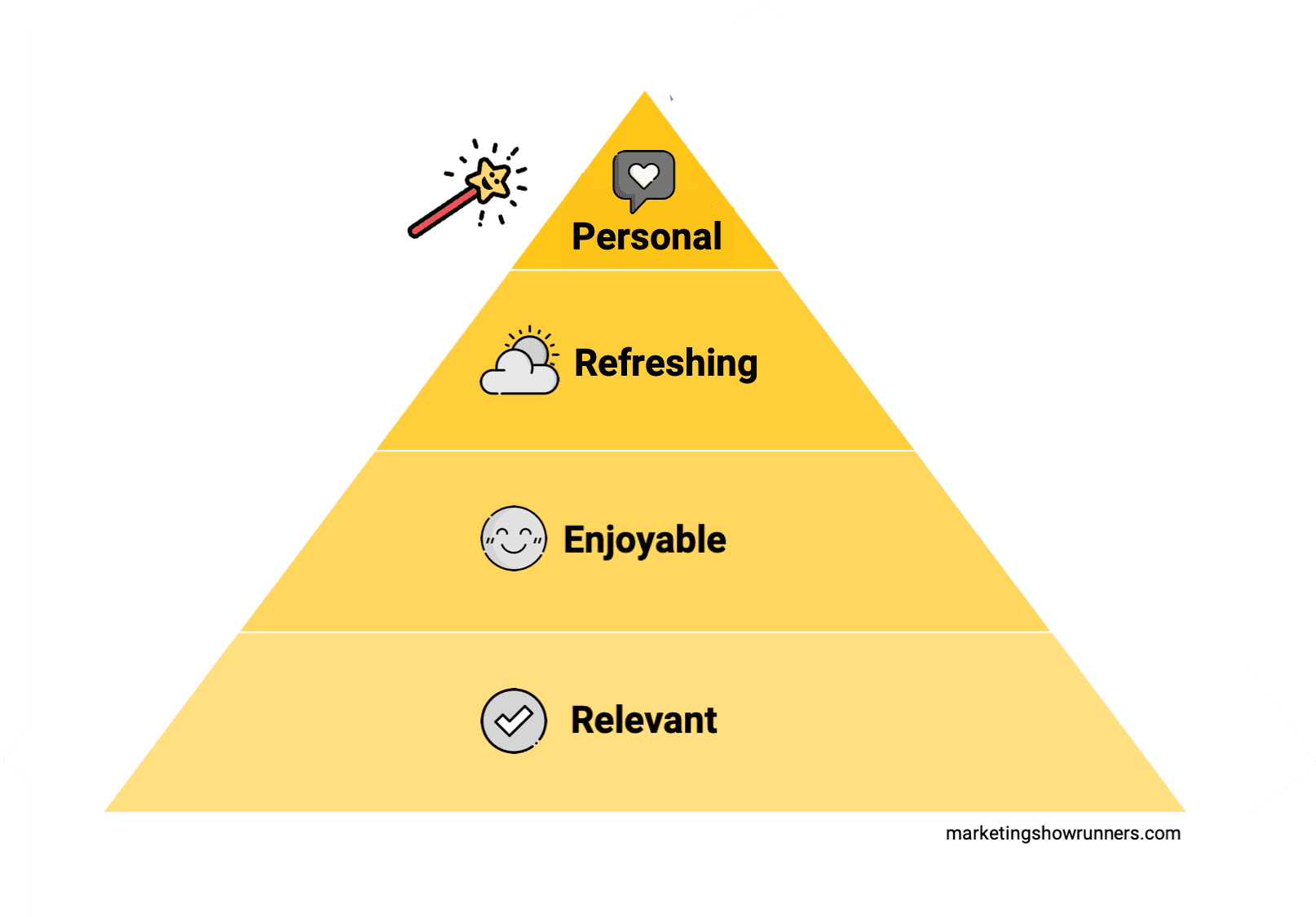

Now then, let’s build the Fortress of Favoritism from the ground up:

The first floor of the fortress: the audience feels your show is relevant.

Simply being relevant is table stakes in any niche. In a world of infinite choice, you aren’t even considered for inclusion in someone’s life if you’re not in some way relevant. This is foundational. It’s also kinda like saying “we exist,” and thinking that’s good marketing. (I know a lot of organizations basically do that, too.) However, just existing isn’t enough to become anyone’s favorite anything. It’s a step in the right direction, but so is leaving your bedroom on the day you plan to climb a mountain.

When you treat marketing as a glorified means of alerting others that you exist, it’s like you’ve taken one step out of your bedroom, then planted your explorer’s flag in your hallway. Mission accomplished! Mountain climbed! (Wait a sec…)

Now, I realize a lot of marketing advice urges us to publish “relevant” content, so let me say this once more for the people in the back: RELEVANCY IS TABLE STAKES. If all you’ve done is make something relevant, you’ve done nothing at all.

The second floor of the fortress: the audience feels your show is enjoyable.

Like being relevant, being enjoyable is pretty table stakes. No amount of smart thinking can make up for a show that’s horrifying to hear. That’s like sticking a textbook into your ear. This plagues B2B brads more than most, since their content is often about teaching smart things. Thus, they sometimes over-index on nutritional value and forget that it has to be delicious when consumed, too.

Regardless of the niche, if there are options (and in most things today, there are), nobody will choose to invest time in anything that isn’t enjoyable. So it’s table stakes once again. They need to feel something more about our shows and about us if we’re to become irreplaceable.

The third floor of the fortress: the audience feels your show is refreshing.

![]()

“Refreshing” doesn’t merely mean “different.” The conventional advice is to be different to stand out. I get that, but you can be rather abrasive and unwelcome and stand out. You could also just be plain weird and gimmicky. What if I gave my next keynote speech with my back to the audience the entire time? I’d be different! In fact, I’d be the most successful speaker on the planet if the task is to be different. But would I be any good? Would anyone actually want me to deliver my talk facing away from them?

(Please don’t say yes?)

(They’re just my feelings. They’ll heal.)

What if your show wasn’t just different in some gimmicky way, but instead, it was different in a welcome sort of way? That would be something we could call “refreshing.” It’s a welcome change from the status quo.

Remember: we aren’t judging any of these things along this diagram. This is how the audience feels. That’s why “refreshing” is better than “different.” When we aim to feel different, we’re implicitly asking, “Different FROM whom?” The competition. That’s not our goal, however. When we aim to feel refreshing, we’re implicitly asking, “Refreshing TO whom?” The audience. Serving them very much is our goal.

The top floor of the fortress: the audience feels your show is personal.

This is where we hope our shows land in the minds of our audiences: the very top of the fortress. It feels personal to our audiences.

Let’s update our lightbox and complete the 3 P’s of Transformational Experiences (click to enlarge):

Okay first of all, you put this in my head, remember? I waved you with my right hand, and you revealed a concept to me.

And second, I mean … Pyramid of Favoritism? That doesn’t even sound good. For this to work, you’d have to call it something alliterative, like the Pyramid of Partiality.

Mwahaha. Dance puppet, dance.

So, the Fortress of Favoritism … which is the name of the thing … can also follow our previous two tools by adding two black arrows to it. You may recall the arrows of both previous spectra.

The Experience Spectrum’s delineates between experiences typically or best experienced quickly by one person versus experiences typically or best experienced with a group:

The Style Spectrum’s important black arrows delineated between your making purely objective observations in your show and you building on top of those things to share subjective beliefs:

The Fortress of Favoritism also has two black arrows, one on either side:

Looking at the left side of the fortress, we can see that our listeners have a lot of options for shows that feel relevant, while a good number are enjoyable, and some are refreshing. We want to be at the top, where just a few shows feel personal to them.

On the right side of the fortress, we can see that shows which are merely relevant are forgettable. They offer enough to get a quick moment in the sun perhaps, but then they’re washed away in a sea of sameness. On the other extreme, shows that feel personal are irreplaceable.

That’s where we want to be. That’s how we want others to feel about our shows, our brands, and us. We want to be on that very short list of things that feel personal, because if we’re on that list, we become irreplaceable.

If your audience feels that your show is relevant AND enjoyable AND refreshing … then your show just might feel personal to them.

Maybe.

Eventually.

I mean, we can’t say for certain.

It’s scary to admit, but we need two things at this point: time and hope.

Yep. We need them to spend a lot of time with our shows. (Okay, that’s not too scary-sounding I guess.) Then, all we can do is hope. (Okay, that sounds watch-a-movie-through-the-holes-in-a-quilt-level scary. What the heck?)

I’ll explain.

It takes time for something that’s relevant, enjoyable, and refreshing to become deeply ingrained enough in parts of someone’s life that it starts to feel personal. We know this. We’re fine with this.

For instance, maybe yours becomes their go-to show during their morning walk or while washing the dishes. Maybe they have experiences like mine with Radiolab. Maybe they just need to get to know the hosts and their quirks, or the recurring jokes or segments, or the various themes and ideas weaved throughout, before the relationship forms. They’re joining a proprietary journey you’ve provided everyone in your audience. It’ll take time for them to feel like a true member of this adventuresome group.

Fortunately, shows are the perfect vehicle for when something takes time.

Serialized content is built expressly to hold attention over time.

Shows are all ABOUT time spent. They’re about going deeper in a world trending shallow.

A show is a vehicle built to accelerate trust and love — which are the sole reasons marketers have jobs, by the way. Unlike the old interpretation of marketing, or today’s bastardized version, show’s aren’t about “grabbing” attention. They’re about holding it. They don’t expand the top of the proverbial funnel but rather straighten the entire thing. Anyone who spends time with our shows feels so connected to us, that they approach everything else we publish, create, and share with them with a favorable, irrational bias. Said another way: Shows make the rest of your marketing and sales more successful.

This only happens because of that relationship others feel they have with us, which only forms over time. Shows are built for that. Overtly. Strategically. Specifically. If you want to sound like a cold marketer for a moment, shows are far more about audience retention than acquisition and growth.

So the fact that our shows only feel personal to the audience over time doesn’t sound too scary. No big deal — that’s what shows are for.

(In future posts, once we have our final compass, we’ll explore how to craft our shows to hold attention. Be sure to subscribe to our weekly email so you get each idea and a bonus story/video from me every Friday.)

When someone spends a lot of time with us, we stand a better chance to establish that personal connection. But that’s all it is: a better chance. And therein lies the hope part of this.

We can’t actually control the way others feel or act. Not really. It’s too messy, too dependent on the individual on the receiving end of our work and the science of how we as humans decide we like what we like.

According to Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, author of How Pleasure Works, we like what we like because of a complex array of things. It’s hard to pinpoint just one reason, since encountering any experience or thing or person causes our brains to “synthesize sensory phenomena, ideas, memories, and expectations” all at once, which then results in us saying, “I really like that.”

You might just simply say a thing is your favorite, but to reach that point, your brain was making much more complex connections and decisions over time.

When you really consider those factors (our senses, ideas, memories, and expectations), you can just sum it up with one simple word: You. You like something because of you. Who you are, what you’ve experienced, and what expectations you now have all matter.

Writes Bloom (emphasis mine), “What matters most is not the world as it appears to our senses. Rather, the enjoyment we get from something derives from what we think that thing is.”

We imbue things with meaning. They don’t inherently have meaning. It’s why, all the way back in Part 1, we realized that commodities are useless … until you have a better story of what could be.

Creating a better story of what could be is the way we maximize both the Experience Spectrum and the Style Spectrum. It’s also how we give ourselves the best chance that our work becomes personal and irreplaceable to our audiences. (In a future post, we’ll review how to craft a better story of what could be. Remember to subscribe.)

“It may not be necessary or even possible to make a product physically better at what it does,” says Bloom. “What you want to do instead is tell people things about the product that make it more pleasurable. Tell them it is special—it’s very old or it’s very new. It’s what the celebrities use. It was made on an estate in Scotland. It was made in the finest laboratories. You give it a story, and people’s experience resonates with the story.”

All we can do is give ourselves a better chance. We can increase our odds, but we can’t say 100% yes it will happen. The problem with the Fortress of Favoritism, and the problem with all marketing (though demanding execs and bogus thought leaders try to convince us otherwise) is we don’t control the outcomes.

We can put out work that maximizes the Experience Spectrum and Style Spectrum. Does the show take them on a proprietary journey? Do we bring our full selves to it? Great, we stand a better chance of seeing the response we want. But that’s all we can control.

Leads. Sales. Followers. Fans.

Trust. Love. Affinity.

These are just some of the things that can happen as byproducts of doing the work. The language we use in our industry hides the fact that they are byproducts, like happy accidents, nothing more. We hear things like “generate” leads, “capture” demand, and “drive” sales. But that’s as ridiculous as when a spurned young lover in a cheesy movie shouts, “I will MAKE THEM love me!”

Not how the world works. Sorry.

All we can do is give ourselves the best chance possible. Then we have to hope they reciprocate.

Now, make no mistake: It’s not a blind hope. It’s not an ill-informed hope. It’s not a hopeless hope. We take steps to understand our audience, to serve them, to proactively create a better experience and bring our full selves to our work in the process. That’s what real hope is, definitionally speaking:

Hope: To expect with confidence.

But hope it is, and hope we shall.

That’s scary as hell when you run a business, no? “Hope”? But it’s reality, and we’re better off facing it head-on, eyes wide open, rather than burying our heads in the sand.

We can control what we can control: crafting a better story of what could be. Ensuring our shows are consumed like proprietary journeys instead of useless commodities. Ensuring we bring our full selves to the work instead of being totally removed. Putting out that kind of show is all we can do. Then, with time, we hope that others reciprocate. We hope we feel personal to them, so that we become irreplaceable. We hope we become their personal, preferred pick for a specific purpose.

We hope we can be their favorite.

Section 2 of 2: Completing the Compass

Whew. Alright. We’ve come this far! Let’s put all our hard work across three straight mega-posts together to finally complete the navigator’s most important tool. Introducing…

🧭 The Creator’s Compass

Remember, if we wanted to get really good at following directions on a map, all three of these mega-posts would be far shorter and feel more like a prescriptive list of steps we can blindly follow. But if all we can do is follow directions on a map, we’re not prepared to find solutions when we encounter obstacles in our way — and there are always obstacles. We’re also not ready to adapt when the terrain changes — and there is always change.

We don’t want to be great direction-followers. We want to be great navigators. And every navigator knows how to use a compass.

So without further ado (and man oh man, do I loooove ado), I’d like to introduce you to our completed tool:

(If you’d like to download your very own Creator’s Compass, click here.)

We’ve been spending all this time across three mega-posts to re-think things. Together, we can now use this tool to become great navigators. This is our compass, useful no matter what situation we walk into, no matter our industry, our personalities, our resources, or our locations. When we encounter obstacles in the middle of our chosen path, we can navigate around them. If the entire terrain changes, as it so often does, we’re able to continue despite that change.

Using the Creator’s Compass, we can easily find our truth north (it’s pointing right at it!), get our bearings, and figure out the answers on our journey — leading the way for others who are with us. This unfolds on two levels: (1) behind-the-scenes, as you embark on a journey with teammates or clients or friends to create a show capable of being your audience’s favorite, and (2) publicly, as you embark on a proprietary journey together with your audience, which feels inspired to join you.

Understanding the Experience Spectrum, the Style Spectrum, and the Fortress of Favoritism allows us to understand how to use the Creator’s Compass. Those are the component parts of the compass after all. But now, it’s time to make good on my promise. We have to switch from re-thinking the work … to doing it.

It’s time to take action. Now that we have our compass and know how it works, it’s time to venture into the jungle standing between us and the mountain peak we see in the distance: creating a show they feel is personal and irreplaceable.

It’s time to be their favorite.

NEXT TIME: We use the Creator’s Compass to craft a better story of what could be.

![]()

PS: For those who have enjoyed these posts, an experimental project:

If you’ve read all three posts, or even just one, thank you! The reaction to these articles has been profoundly motivating, and very gratifying, and also completely stressful. (Is this how I have to write all the time now?) Anyway…

I’d like to invite you to an experimental project: I’m looking for a small number of podcasters who enjoy being early adopters and movers to participate in the Alpha sessions of our workshop. This is NOT a recorded video series, nor a single day of feeling good before going back to work. This is an ongoing, interactive, cohort-based experience, where we use the system we’re crafting to do real work on our real shows together (live calls with me, projects we execute together, and group support and connection).

If you’re interested in participating, please email me at jay@mshowrunners.com, and I’ll share more details. The workshops’ earliest students will also become the earliest members of an alumni group who feature heavily in future content and continue to help each other and future students behind-the-scenes.

Three requirements to enroll: (1) you have a show or at least a placeholder episode up and running, or can do so before the workshop begins … (2) you’re excited by the earliest, most raw versions of things. These are the Alpha sessions for a reason … (3) you personally host the podcast.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com