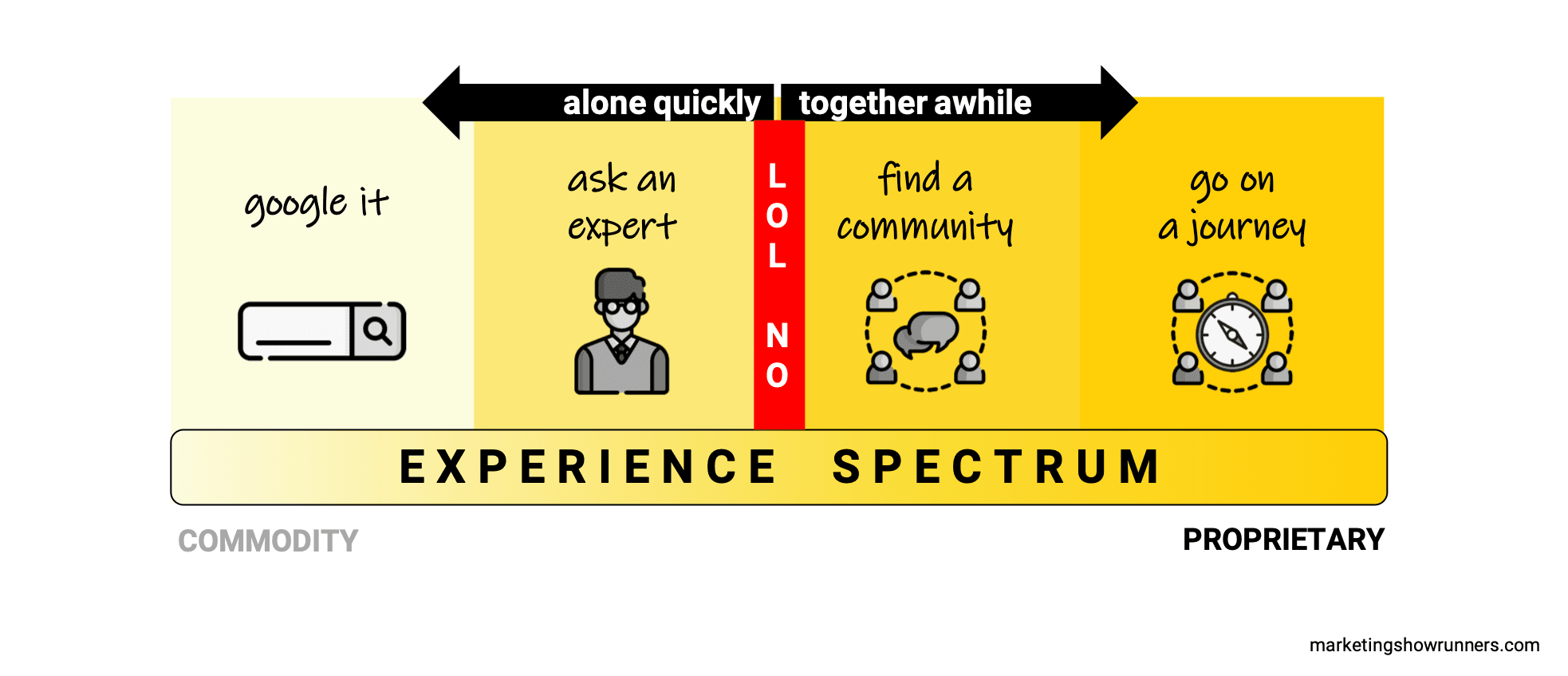

The Experience Spectrum

This is the next step in our ongoing journey to answer a crucial question: What does it take to create someone’s favorite podcast? Each week, a new idea takes us one step closer to developing a system we can all use, as well as an online, interactive workshop where we can do real work on our real shows, together with our peers. To join the journey, subscribe at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite.

![]()

Throughout this series, we’ve been exploring one crucial question marketers should strive to answer when making a podcast. The question flows from a logical series of statements, but the statements unfortunately create a bit of a problem for us. Below are the statements. See if you can spot the problem:

We want to be among someone’s favorite things.

That’s because the job of a maker and marketer is to earn the trust and love of your audience.

To earn trust and love, you first need your audience to spend time with your work.

Before anyone spends any time with your work, they need to choose you and, more importantly, choose to stick around. Our work isn’t about who arrives. It’s about who stays.

But in a world of infinite choice, people only choose to start and continue experiences they know will be the best investments of their time. Infinite choice + limited time = spend time with only your favorite things, and avoid the rest.

Thus, we need to be among their favorite things.

See the problem? The logic here isn’t linear. It’s circular. It starts and stops with this idea that we must make something others consider among their favorite things. It kinda feels like what recent grads go through to get a job: Everyone wants me to have experience before giving me the job, but to get experience, they have to give me the job.

We have to be their favorite to earn trust and love. But to earn trust and love, they need to choose us and spend time with us. But they only choose and spend time with things that are their favorite things.

Chicken, meet egg. Or maybe it’s the other way around? My head hurts…

Lest we get too stuck on the semantics of which thing happens at which point of someone’s relationship with us, I’ve decided to boil it all down to that one overarching, rather-complex concept: make their favorite podcast. You, me, our teams or clients — all of us are on a journey to do that, the moment we start thinking about making a show. That’s the ultimate goal of any podcast. What if we could become their favorite?

Imagine that.

So far, we’ve detailed why being their favorite show is the ultimate goal of your podcast. We’ve identified the problems with our usual approach to reaching that goal. And we’ve established a couple important definitions — what we mean when we say favorite (someone’s personal, preferred pick for a specific purpose) and why earning trust and turning that trust into love is what it means to be a marketer.

After allllll of that, it feels like we’ve only scratched the surface in this pursuit of truth, and so today, I’d like to share a crucial realization:

This is, like … hard.

In that earlier piece describing the problems with our typical approach to podcasting, we identified the main reason why a podcast from a brand typically doesn’t become anyone’s favorite show: Marketers often create transactional shows. This doesn’t mean marketers try to sell someone something inside the show (though that happens too). Instead, it’s about the type of value inside the show — transactional value.

The typical marketer-made show tries to answer very narrow questions that can likely be googled or learned more easily by scanning a bulleted list, a blog post, or (gasp) a full-episode transcription as a replacement for actually listening to your show. This is the nature of transactional value, which I define like this:

Transactional value is education or entertainment others seek in reaction to a problem they’re trying to solve as quickly as possible. The purpose of any content sharing transactional value is the transaction itself, i.e. the quickest, easiest transfer of knowledge from the creator to the consumer. The consumer’s main focus is getting beyond the content to possess the knowledge. The experience of consuming the content is not the goal. The acquisition of information is.

In this way, transactional shows are like any transaction: the point is to finish them. The resulting benefit is what others really want.

If we’re going to earn trust and love, we need to create something they want to spend significant time with instead — not merely use as a hollow utility. There needs to be an emotional benefit as much as a tactical one. Listeners shouldn’t want to speed through the episodes or skip the experience entirely in favor of a transcript or list of key takeaways. The driving reason they want to listen should be because they want to listen. The transaction isn’t the main benefit. The experience is.

I like to remember all of this with one simple phrase: Great marketing isn’t about who arrives. It’s about who stays. As part of any individual or team’s “great marketing,” a show should abide by that idea. It shouldn’t be transactional. It should be such an enjoyable, emotionally resonant experience that people want to stick and stay. The process of consuming it is the value itself.

Today, we try to bridge the gap between transactional shows and what we should create instead: Transformational Experiences.

So how do we do that? Again, this feels, like … hard.

I mean, it’s not like there’s a magic wand to make complex stuff not quite as complex.

Well, shoot.

Okay then, let’s go after this thing. Here’s how we’ll make sense of this complex problem.

How We’ll Make Sense of This Complex Problem

This is Part 1 of a three-part mega-series. Over the next three weeks, we’re going to explore three crucial concepts that, when combined, can re-frame how we think about our shows, such that we can create someone’s favorite show.

I think re-framing exercises are incredibly important, because they force you to put aside conventional wisdom (e.g. a B2B podcast should be an expert interview show) and daily stresses (e.g. budget issues, time constraints, other projects aside from your show — the giant list goes on). Let’s take about 60 minutes total across three weeks (or 0.83% of your work time, if you work 40-hour weeks) to step back from all that stuff and rebuild our understanding of making shows from the ground up. This is also known as reasoning from first principles.

This is kinda like stepping back from reading a map each step of the way to learn how a compass works. The former makes you good at following instructions. The latter makes you a great navigator. We are now in the business of being great navigators. No matter how the terrain changes or where we want to go, we’ll be equipped to get there — and lead others there, too.

We’ll learn about three core concepts in the process, with one mega-post per concept:

1) How do others experience our show?

2) How do we personally influence that experience?

3) How do those two things combine to affect how others feel about the show?

In other words, how do different types of experiences (#1) and different ways we could get involved in crafting them (#2) ultimately lead to someone declaring, “That’s my favorite podcast”?

Once we understand all three of these things, we’ll be able to think better about this work. We’ll be true navigators. After that, we’ll start hacking away at the jungle standing between us and that faraway mountain peak we want to reach, using the three concepts we’ll learn in these next three posts as tools to make actual progress on our actual shows, together.

Sound good? Nod if you agree.

Did you nod? That’s weird. Stop nodding, weirdo. I’m not actually in the room with you. But I’m touched you feel like I am. We’re friends now.

Alright, let’s dive headlong into #1 in our list of concepts required to craft transformational experiences:

How do others experience our show?

Let me see here, I guess I can just take that magic wand back out and use it to get us started.

Okay. Let’s see, how does this thing work?

Ah, right, here we go:

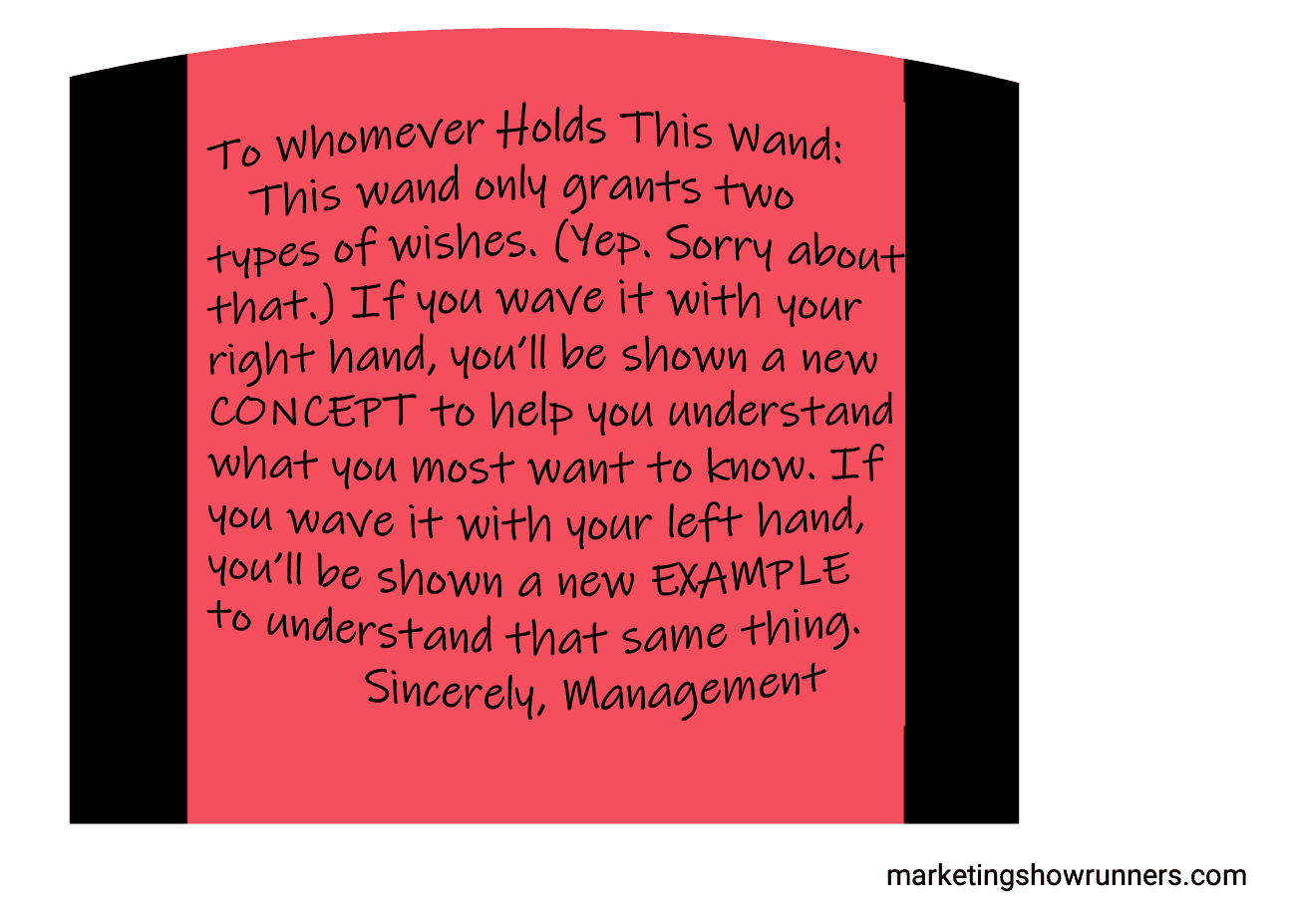

Welp, that kinda sucks overall but is bizarrely perfect for our situation today, almost like it’s a conveniently concocted plot device to take us through what could otherwise feel like an intimidatingly long post. But nah, probably just coincidence.

Welp, that kinda sucks overall but is bizarrely perfect for our situation today, almost like it’s a conveniently concocted plot device to take us through what could otherwise feel like an intimidatingly long post. But nah, probably just coincidence.

Alright, so, let’s focus on the thing you and I most desire so that this wand actually works. (I will temporarily set aside other things I deeply desire to know, like how sentient thought happens in a species, or whether there’s an afterlife, or how space can be expanding infinitely, or how my New York Knicks can be this incompetent for this long.) I’ll focus on one question: How do others experience our shows? How can we get into their hearts and minds and see our work from their perspective?

(Visualizing. Visualizing. Squinting eyes real hard because that helps people think for some reason. Wait, why do we do that? Hold on, no! I don’t actually want to understand that. Back to the podcast thing … placing the wand in my right hand… aaaaaand flick.)

Okay. What are we looking at here exactly?

What the — you can talk?

Fair point.

But just so I understand this: You can only grant two very specific types of wishes, and also you can talk. That’s the scope of your powers?

Oh. Uh huh.

Oh, erm, yes. Of course!

So the Experience Spectrum?

Wait, why did I know that? Like, in my head, I was thinking that exact definition as you said it.

Wait, why did I know that? Like, in my head, I was thinking that exact definition as you said it.

Oh, right! Wait, I read your, um … your butt-tattoo … and I don’t even know your name. What do I call you?

Bob? Your name is Bob? Bob the Magic Wand?

I mean yeah, kinda? I wrote a book about questioning stuff. So…

Ahem. Right. Doesn’t matter. So the Experience Spectrum?

Right, and since I understand this now thanks to you, Bob, I can take it from here for a little while. Because of magic. Definitely not because of my limited design skills and the impossible task of making this whole article a back-and-forth between us.

Let’s dive into the Experience Spectrum.

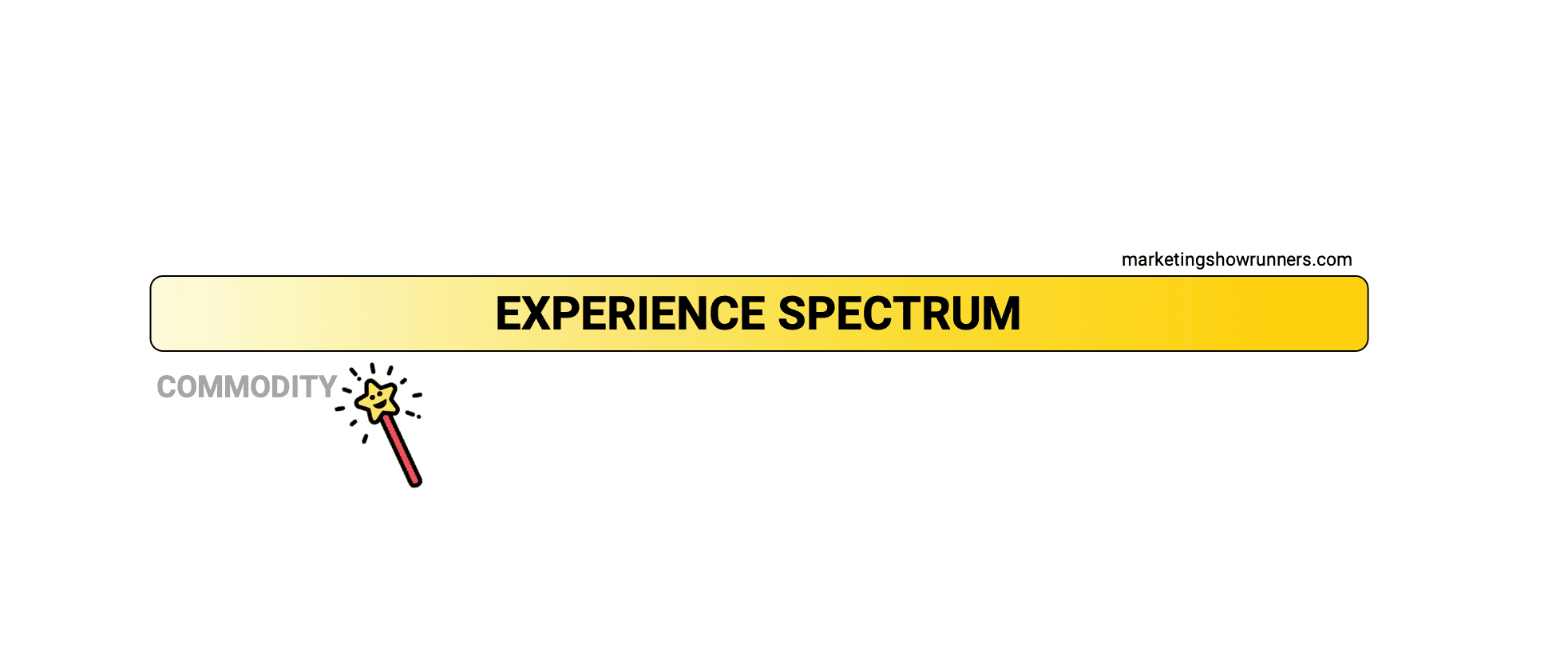

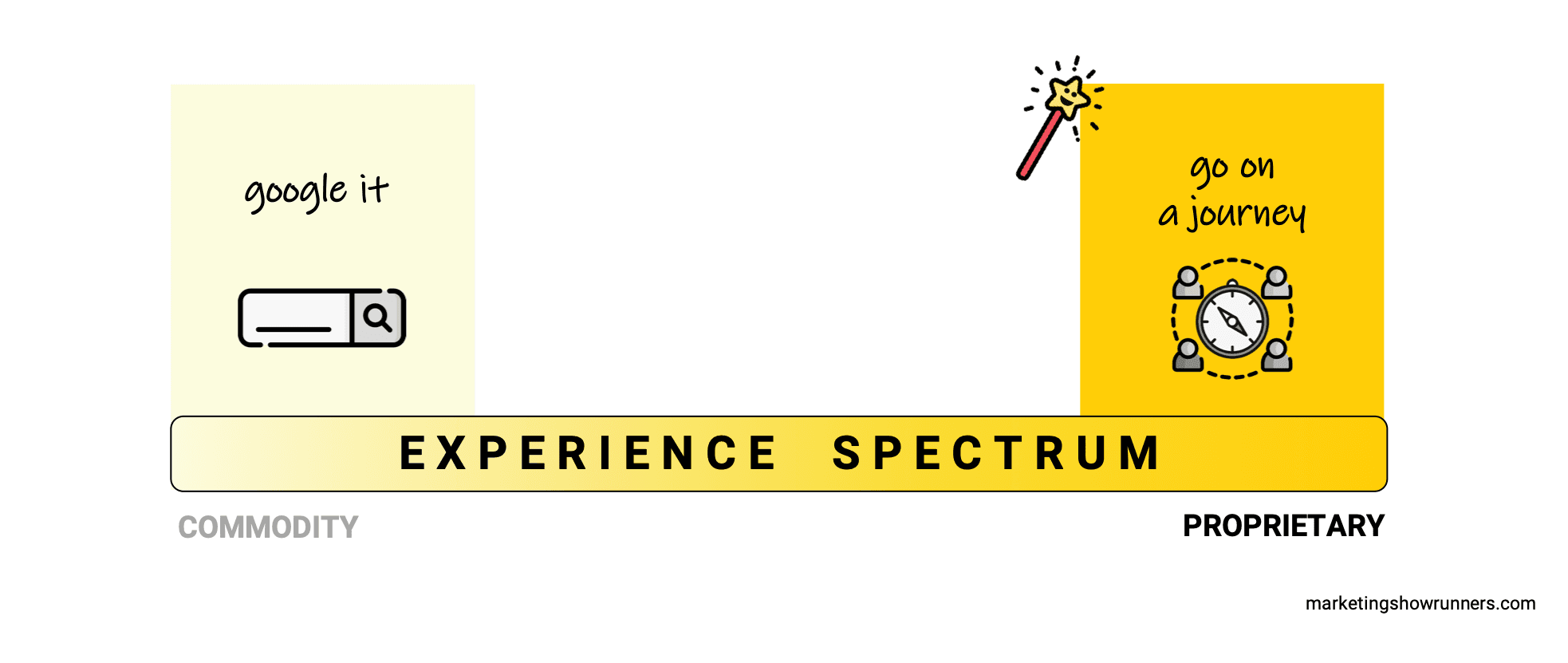

The Left Side of the Experience Spectrum: Commodity Experiences

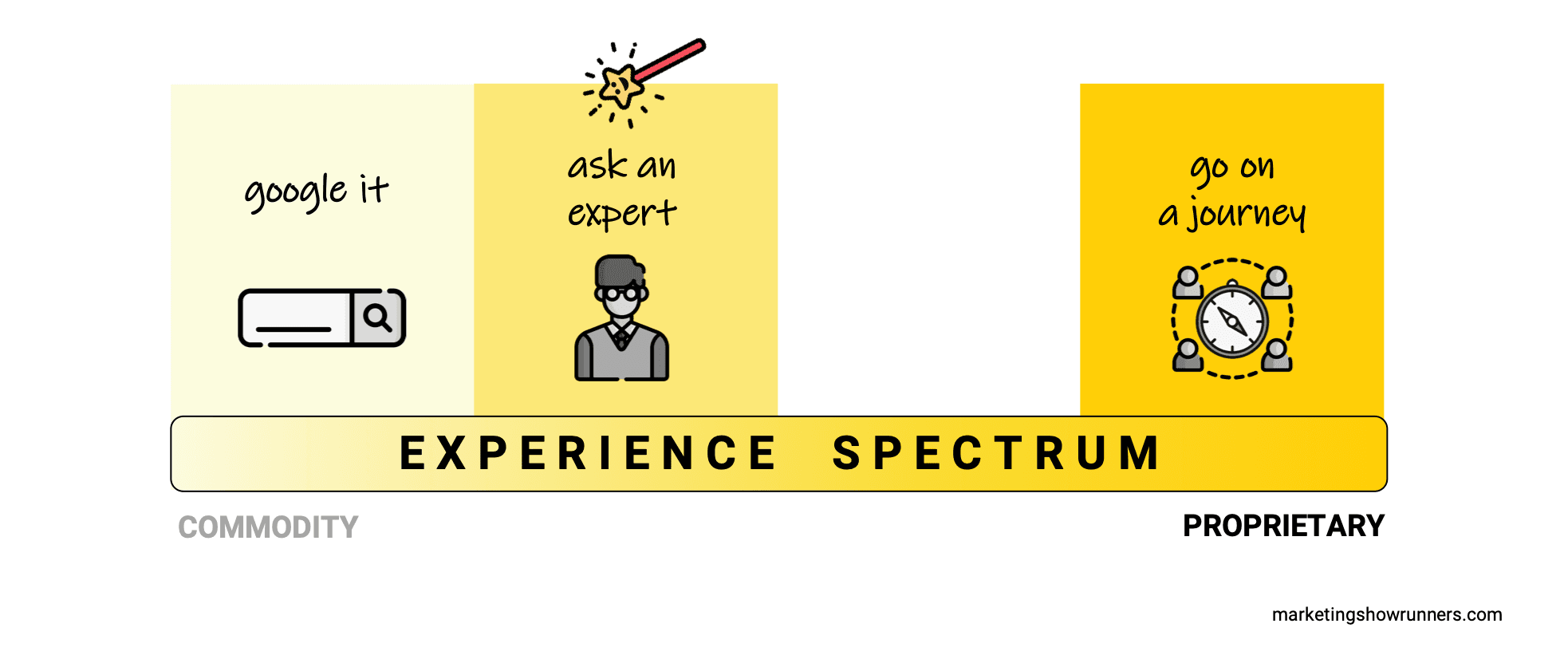

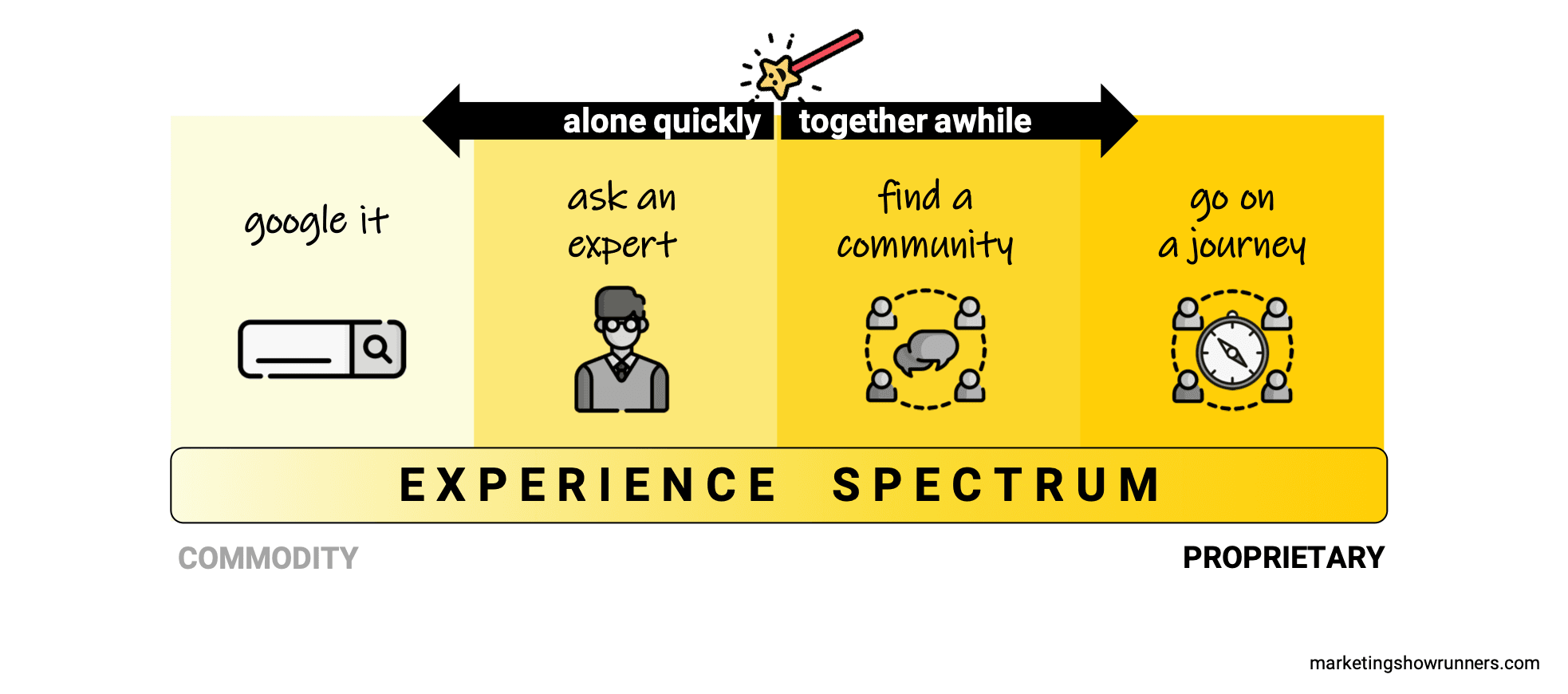

The Experience Spectrum reveals all the ways others might experience what you’re creating for them. Literally. How is the thing interacted with or consumed by someone else?

On the far left are commodities.

These are dangerous things for us makers and marketers to create and offer our audiences — podcast or otherwise — because they’re so darn common, any one commodity doesn’t matter much to anyone. Commodities can be bought or sold (or experienced/consumed, if we’re talking about content) quickly and easily.

Making matters worse for people who create and offer their audience a commodity experience, the source providing that experience doesn’t matter much — i.e. the person, team, and organization. Gold is gold. Corn is corn. Iron is iron. Content teaching you how to use Instagram ads is content teaching you how to use Instagram ads. All of them are commodities. All of them promise the same exact value in their “raw” form, and so the source of that value doesn’t actually matter … until the creator behind it begins to tell a better story. The story about the commodity is what we might call a brand. (I define brand as “how others feel about the collective behavior of you and your team” because a “brand” doesn’t exist. It’s an empty shell of an idea until people do some work to create a feeling in others.)

Later in this post, we’ll talk more about why and how a story can evolve a commodity into a far better, much more unique experience. For now, just remember this:

A commodity is rather useless without the story of what could be.

A commodity is just a raw asset, until you and others understand what could be now that you’ve created or received the asset. What does owning the commodity (or experiencing it) enable someone to do? What does it say about their identity to others, or what can it earn them from others?

Handing you a soft, shiny, yellowish metal — and leaving it at that — is rather useless. It’s like saying, “Here’s some gold. You have some now.”

Not much value there, really.

And if you’re thinking, “Wait, there’s a ton of value. It’s gold!” … that’s a sign you know the story of what could be.

“Here’s some gold. You have some now. And because you have some now, you can do all kinds of things: create some jewelry to feel beautiful or make someone else feel beautiful; trade it for goods and/or services you need in your life; give it to someone else as a donation so that they can trade it for what they need in life; give it to someone as a loan or investment, so now they have to repay you a total worth more in value than the initial amount you gave them; or just stash it somewhere if you believe people in the future will value gold more highly than they do now, which means you can do more with that gold later than you can right now.”

Only when someone starts to see what could be, aka the story around the asset, does the commodity seem like it has much value. And when something seems like it has value … it actually has value. For something to have value, one or more people have to believe it has worth. Perception is reality in this case. The only reason a dirty green-and-white piece of paper with a dead president’s face on it is valuable in the United States is because we all agree a dollar is valued at a dollar and can be exchanged for goods and services accordingly. It’s just a dirty green-and-white piece of paper with a dead president’s face on it! But we all understand the story of what could be, so it becomes valuable. Perception is reality.

Thus, the difference in a commodity’s value to others is the story of what could be. In fact, if you really think about, the story is the actual value. Without it, the metal, the grain, the lumber, the green-and-white paper, or the information you publish as content are all rather useless. The story makes them seem valuable, so the story is the value.

Now, I realize it’s kind of hilarious to imagine that somebody in our society has no idea what gold is, or wheat, or iron, or money, and thus they have no clue why any of these things are valuable. Weird and kinda funny to imagine. So let’s take this more squarely into our world as content creators, because we often dance dangerously close to the left side of the Experience Spectrum and create commodity content … no story attached.

It’s Dangerous to Create Digital Commodities

We might not be sharing gold or wheat with our audiences. Instead, the raw asset of our work, the commodity itself, is information. It might be educational or purely meant to entertain. Either way, when we create our work, we’re packaging and distributing information. That’s the commodity on offer from us.

Like physical commodities, information is pretty darn common, and making matters worse, we often focus on sharing information we know is in high demand … which only means we enter highly competitive markets for an undifferentiated commodity. Let me try to put this into a marketing context in such a way that you might nod your head clean off your neck.

Commodity content is what happens when you focus on the algorithm, not the people.

We’ve been living for years now in this arms race for content that ranks higher on search or hits hidden tripwires on a social network (“engagement” in the form of tagging a million people or posting sensationalist things or playing to the lowest-common denominator in topic and style — whatever will trigger the algorithm to promote our content more broadly). That’s commodity content. It seeks to pander to the market, instead of change people and things for the better.

At its core, commodity content is common as all heck, because it answers common questions. What’s the best time for a business to tweet? What’s hot in fashion in 2020? How can I get promoted? What happened last night on The Bachelor or in the NBA Finals?

Addressing oft-asked, easily answered questions on your podcast is no way to make someone’s favorite show, and I plan to make that case — today and throughout this series. (By the way, if you’re not part of our weekly journey, we’re essentially building a system to craft better shows, together, and publicly. You can subscribe via email for free.)

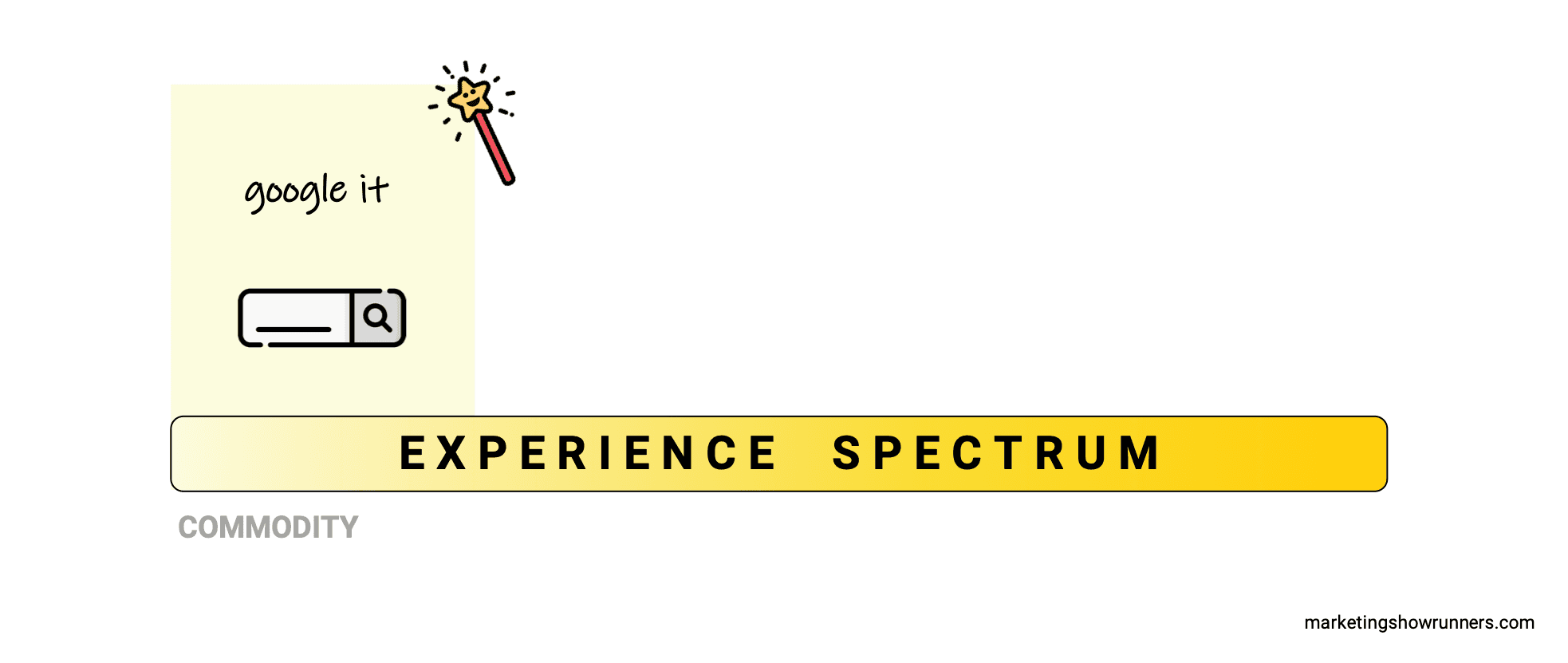

Ask yourself: What’s the best possible experience at our disposal today if we want to ask a common question to get an easy answer?

Bob, if you can be so kind…

Yup. This is the problem with so many podcasts built by brands today. They’re commodities. It’d be a better experience to search for and scan the information quickly than to spend an entire episode — or multiple — actually listening,

If we’re going to make someone’s favorite show, we can’t merely hand out commodities. “Here’s some gold. You have some now. Here’s some knowledge. You have it now.”

To create someone’s favorite show, we have to ensure others experience something greater than just the raw asset itself. In other words, we have to lead with and promise others the thing that actually provides them value — the story of what could be. (Said in a pithy way: Nobody wants a better pillow. They want a better night’s sleep.)

The difference between focusing on the raw asset versus focusing on the story is like the difference between a show that interviews expert guests for their success tips (highly commodified, undifferentiated content today) and a show that interviews expert guests by asking them to deconstruct one favorite side project having nothing to do with their day jobs that they still attribute to their career success. (Whoa, now that could put the “original” in original series.) Even someone sharing the story of their success is a bit better than just handing out success tips.

That’s the problem with commodities. Listeners think, “I can get THIS anywhere. Why am I getting it from you?”

Focus on answering, “Why am I getting it from you?”, not merely presenting the “THIS” that people can get anywhere. That’s a commodity. If we white-labeled a commodity show, we would have no clue it was from that particular source.

We have to stop handing out the raw asset alone, like knowledge, like how-to instructions, like tips and tricks, like the biography of successful people, like curated links or recaps. Commodities are rather useless … until we tell a better story.

That’s the far left of the Experience Spectrum that we want to avoid.

But what about the far right? That’s where we want to be.

The Right Side of the Experience Spectrum: Proprietary Experiences

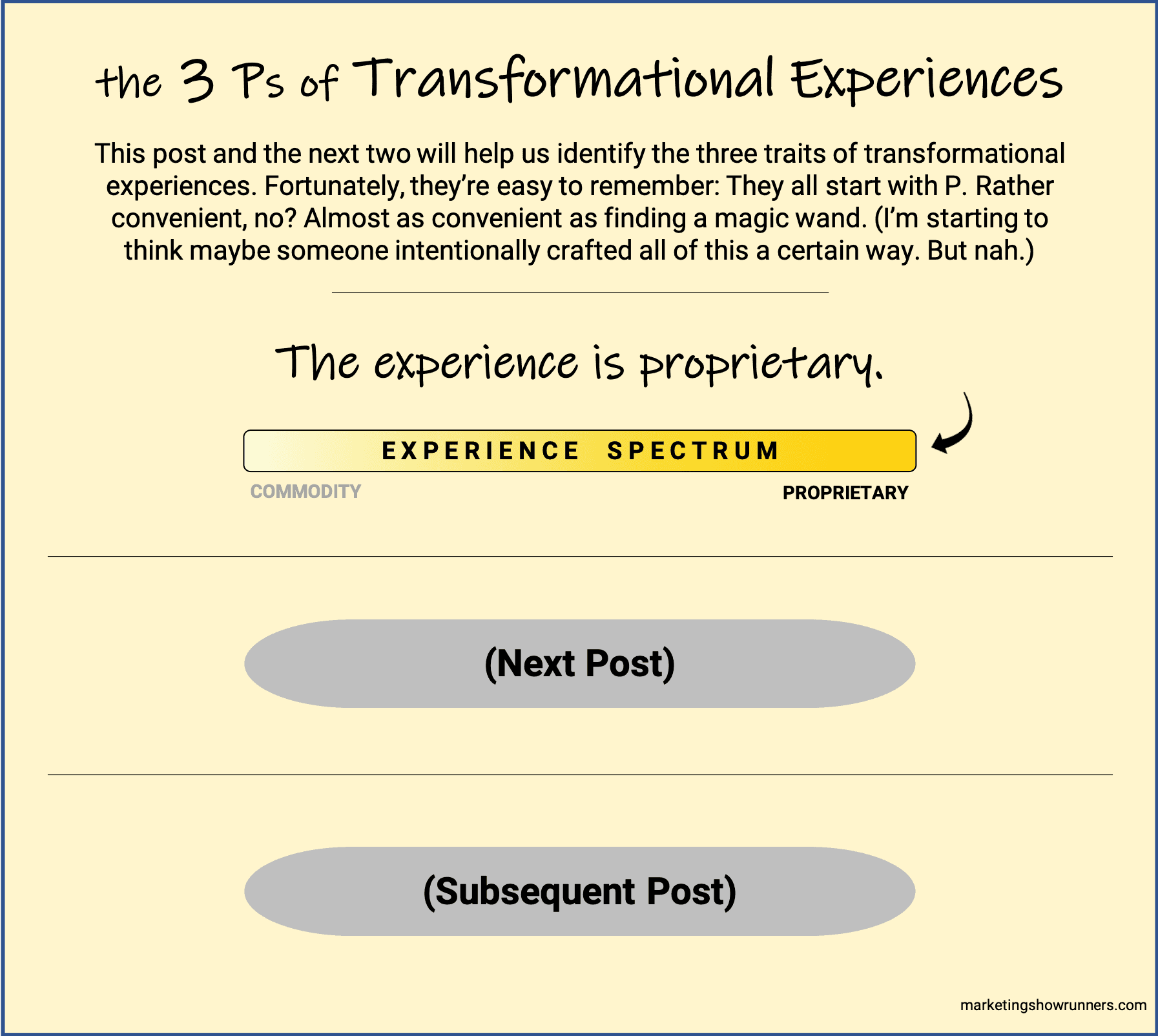

Proprietary experiences are the extreme opposite of commodities.

These aren’t things you can get just anywhere, from just anyone. They’re things you can only get from one particular source. Gold isn’t gold. Shoes aren’t shoes. It’s THIS gold from THIS source. THESE shoes from THIS brand.

It’s not Yet Another Podcast About General Career Success. It’s The Only Podcast That Examines Career Success in This Specific Way. (You get the idea.)

People and organizations that sell commodities start with the raw thing, then perhaps use promotional language like slogans or benefits statements or case studies to describe the value. But people and organizations who create proprietary experiences don’t need to describe the value. Instead, they create value. They start with and focus on the story. They know that the story isn’t just what makes the asset seem valuable. The story is the value. It almost doesn’t matter what the asset itself even is.

Here’s what I mean by that…

Think of a brand you truly, deeply adore — one that’s among your favorite brands. Wouldn’t you be more likely to buy just about anything from them than any other brand, even if another brand specializes in that thing? Doesn’t your trust and love in them mean they can release a seemingly irrelevant project — content, product, or service — and you’d naturally trust that it would be good, too? Does it really matter what they sell, so long as their why and maybe their how stay the same?

Decades ago, it would have been totally unreasonable to suggest that Apple would be the world’s most beloved manufacturer of phones, and yet today, it seems obvious. Of course they are! They’re Apple!

One of my favorite YouTube channels is from the gorgeously designed and exhaustively researched science explainer team, Kurzgesagt (meaning “In a Nutshell”). They specialize in digital animations. But when they began to sell physical products, like notebooks, I jumped at the chance to buy my very own gratitude journal based on their beautiful, perspective-shifting video on human dissatisfaction and how to solve it. Kurzgesagt is my favorite brand for science explainer videos. They’re among my favorites for any video about anything at all. They’re among my favorites for any content at all.

As a result, I don’t care what they offer. I’ll at least try it — content, product, or service — and I’m confident I’ll love it.

Theirs is a proprietary experience, not a commodity one. For me, and for their 11+ million YouTube subscribers, it’s not about the raw asset. It’s about the story — both the story they tell about their work, and the story we all now tell ourselves about them.

Like Kurzgesagt, we shouldn’t start our journey to create someone’s favorite show by focusing on just the raw asset — “a podcast” or “tips for being better at social media” … or “science explainer videos.” We should begin by crafting a proprietary experience.

I call that brand IP — something that supersedes even the container itself, i.e. the podcast. Brand IP can be plucked out of the container and expanded, repackaged, and repurposed anywhere. Because people don’t care about the container. They want the value inside.

That’s part of what makes the experience transformative to the audience: It’s a proprietary experience. It can only be found from this source. The story leads. The source matters. It’s proprietary.

Proprietary experiences can’t merely be consumed by googling it. They don’t provide easy answers to common questions. They push you, improve you, delight you, and surprise you. They challenge you and change you. They aren’t best when experienced by a quick search alone on your phone. Instead, proprietary experiences feel a lot more like an adventure together with people who are similar to you.

Proprietary experiences feel like journeys.

This might be a journey of understanding, of self-discovery, of escapism, of physical travel — any way you might define journey.

When you embark on a journey, nobody really has the answers. There’s no proven blueprint. You can’t just google it and be done with the transaction — because it’s inherently not a transaction. It’s far more transformative than that (i.e., we’re on the right path to creating a transformational experience). As a participant in the journey, you don’t want the experience itself to end. You’re there for the journey, the process, the experience itself. (“The journey is the destination” and all that.)

In podcast parlance? The benefit is the listening, not the finishing. Transactional shows are about extracting the value and walking away. End of transaction. Transformational experiences provide a deeper, more emotional benefit — one that listeners can’t wait to immerse themselves in again.

The steps of a journey all connect, sometimes explicitly (with cliffhangers and callbacks and mentions of other episodes to tie them all together in serialized fashion), but more often, they connect implicitly (through an ongoing exploration of the larger themes, shared beliefs and goals, or topical focus areas that tie all the episodes together). When the journey is implicit instead of explicit, there might be no mention of last week or next week, and today’s episode might not require a previous episode to understand, but it still feels like one coherent journey.

Crucially, journeys earn us as creators the time investment we need from our audiences to then earn their trust and love. We stand a better chance of securing a place on the short list of our audience’s favorite things.

Don’t Share Common Answers. Ask Uncommon Questions.

On a journey, no single person has all the answers (including the host of the show), so you embark on a quest together as a group. You’ll find other groups who can help and meet other individuals who make some of the ideas clearer (or maybe magic wands named Bob who can do that for you).

On the organizational level here at Marketing Showrunners, we’re trying to understand what it takes for marketers to find and share their voices, make a difference in the lives of their listeners, and shift the culture for the better as a community. That’s our macro-level journey. Supporting that overarching quest is the journey we’re on right now: How can you make your audience’s favorite show? I believe this journey will come to an end with a system we can all use to do so, and a series of online, interactive, cohort-based workshops where marketers join peers to do real work on their real shows, together. (I don’t believe the macro-level journey will ever end.)

Whatever your journey might be at your organization or in this moment in time, the destination should always be clear to you and your audience, even when the path to reach it is not. As a result, every individual involved is both aligned in the goal but equal participants in determining how to get there. Sometimes, they participate just by consuming and interacting with your work. Sometimes, they offer feedback and ideas. Sometimes, they take the ideas and run in a new direction you didn’t expect. It all enhances the journey.

Thus, journeys are in part incredibly unique each time, because they’re dependent on the source (you) and the participants (your audience) and the interaction between everyone. These quests compound in value. The more people join and contribute, the more the ideas get pressure-tested, and the better the journey gets. On the individual level, the more a listener returns to your show and gets to know you and the ideas you share, the better the show feels, and the deeper the relationship runs.

Don’t let your show feel like something they could have just googled. Don’t create a transactional podcast. Create a transformative experience. Take them on a journey that changes them in fundamental, lasting ways.

Sigh. I was on a roll, Bob. What is it?

Wow, 4,000? Really? You look great!

![]()

I’ll bet. Au naturel.

So, examples?

Right then. Placing you in my left hand, aaaaand (flick!) … now I know some examples.

You really are magic, Bob, thank you.

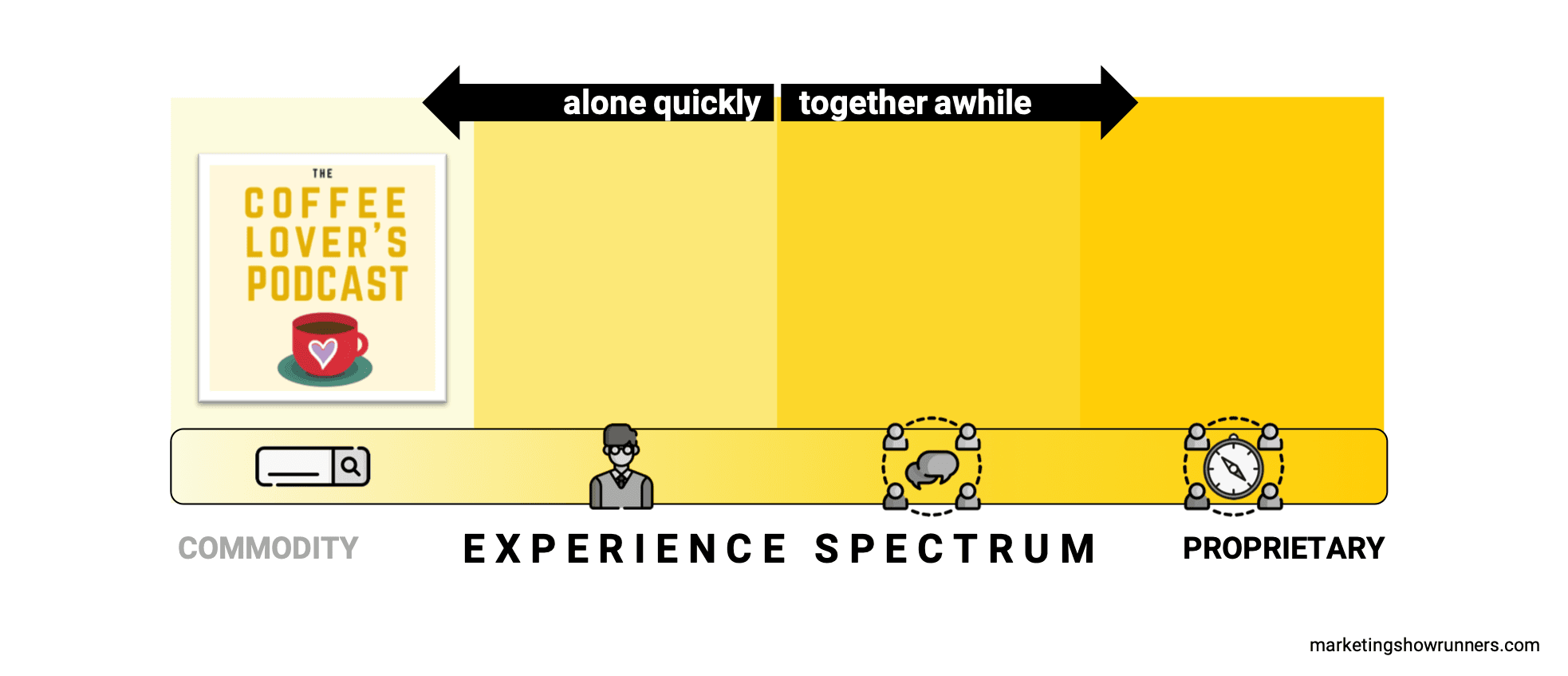

Here are two examples we can use that suddenly popped to mind: a coffee brand and a marketing tech company. We’ll use these two examples throughout the remainder of this post and our next two in this series, tweaking and evolving them for each new concept we’re trying to understand. For now, let’s introduce the shows as commodity experiences, i.e. the left-most side of the Experience Spectrum.

Both shows are effectively roundups of information and little else. They focus on who, what, where, when, and how the news unfolded — all presented plainly by the host. There’s not much “what now?” or “how-to,” or “so what?” or “why?” and there’s no real attempt to entertain. These are purely informative shows.

Coffee brand:

The most commodity version of the coffee brand’s show would describe new blends of coffees, various types of beans to know about, new sources of beans used by the coffee industry, and new technologies.

Starbucks released a new beverage. Keurig has this new tool. Robusta beans are on the rise.

Here’s some gold. You have some now.

Maybe this coffee brand’s commodity podcast would be called something like The Coffee Lover’s Podcast.

(Side note: Don’t get me started on podcasts that use the word “podcast” in their names. Where else does this happen? I mean, who could forget, back in high school, reading The Great Gatsby Book and studying The Declaration of Independence Parchment Paper? Also, my favorite show to rewatch is The Office TV Show, and of course, few films are as beautiful as James Cameron’s classic, Avatar Movie.)

(Let’s move on to our second podcast example before I pick up Bob the magic wand and jab him into my eye.)

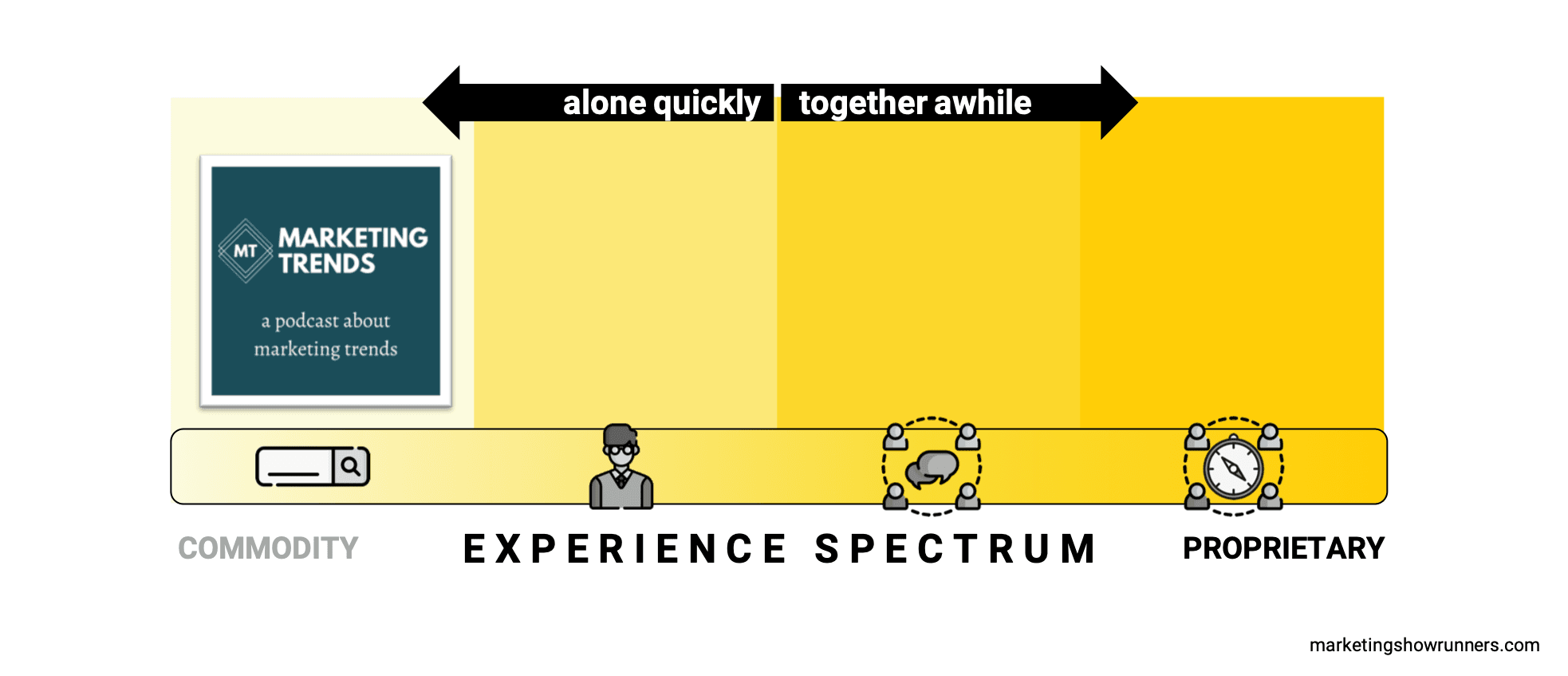

Marketing tech brand:

The most commodity-like version of the marketing tech company’s podcast might be called Marketing Trends.

Mailchimp launched a thing for marketers. LinkedIn published a report. Here are a few influencers who did stuff last week, too.

Here’s some wheat. You have some now.

Again, the problem with commodity shows is that they simply hand you the raw asset, when the power of a show and the value of anything is really the story of what could be. In the two examples above, the creator, the source, and the brand all don’t matter. The experience of either show really isn’t the point. The audience only benefits from having listened. These are transactional shows, not transformational experiences. Hard to earn more time. Hard to earn more trust or love. Hard to become someone’s favorite show.

Fortunately, as we move to the right on the Experience Spectrum, a show starts to morph from rather useless commodities to something more valuable, because it starts to focus more on the story (the thing that creates the value) instead of the raw asset (the information).

So how might our two example shows look if we slid them as far to the right as possible on the Experience Spectrum? What’s the difference between our commodity shows and two shows that take people on a transformative journey?

Coffee brand:

The most proprietary version of the coffee brand’s show is … pretty impossible to describe in general detail. That’s because, once you reach the far-right of this spectrum, the experience is wholly dependent on the source, the provider of that all-important story.

I can describe a commodity show from a coffee brand really easily, because in doing so, I’m describing a commodity show from any coffee brand. If we white-labeled a commodity coffee show, we would have no clue it was any one particular coffee brand. So now, we need to make this real, with a real example, because proprietary shows aren’t Yet Another show. They are The Only show that does what they do.

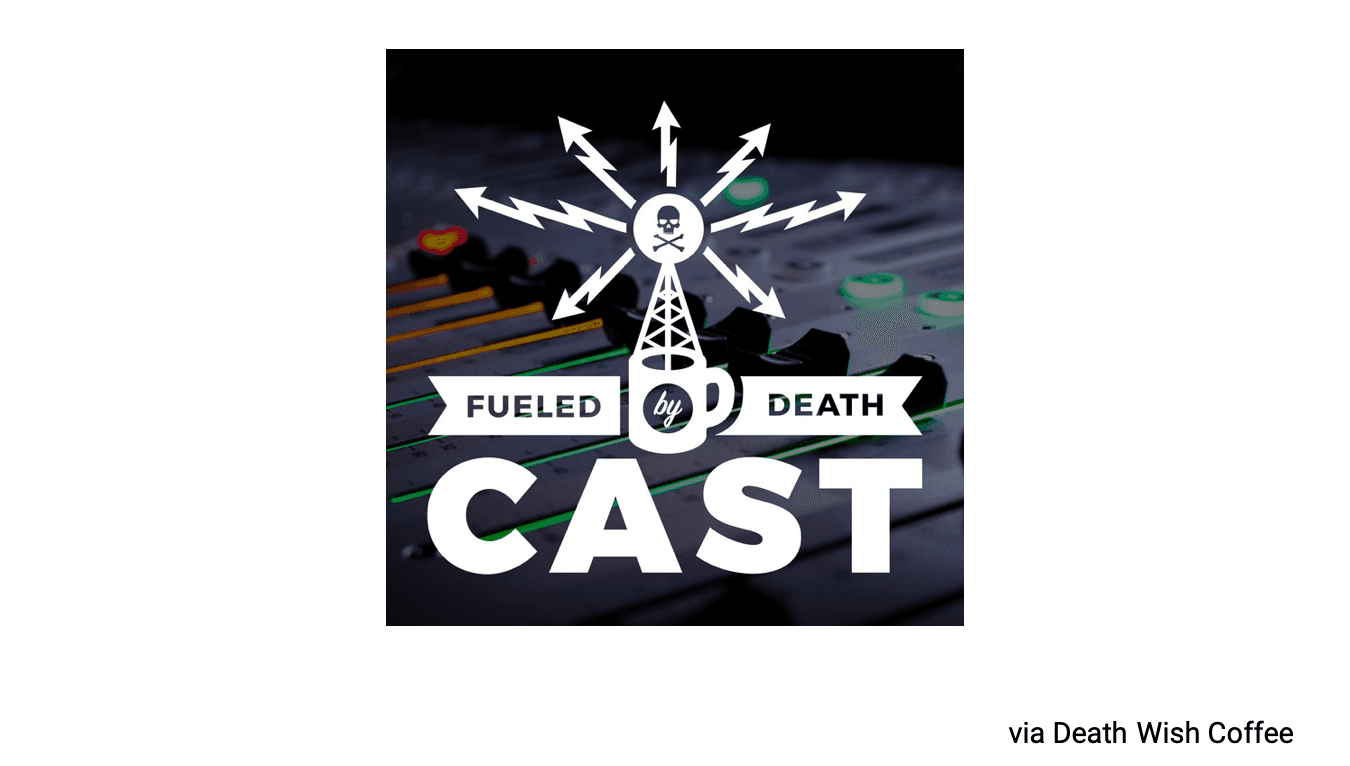

Let’s use Death Wish Coffee, the world’s strongest coffee. Death Wish has a clear understanding of why they exist as a company, and it’s not to sell coffee. They have a better story of what could be as a result of their coffee, and they use that same story to shape their podcast into a proprietary journey.

Their podcast isn’t The Coffee Lover’s Podcast. It’s called… Fueled by Death Cast.

“Death is inevitable. Spoiler alert!” their podcast host once told me. Their show is hosted by Jeff Ayers, the company’s in-house, on-air talent. (Officially, he’s a full-time broadcaster for them. They’re that focused on taking listeners on a journey with their brand.)

The Incredible Jeff, as he’s playfully known on the show, understands that the entire brand exists for a very specific reason. As he told me during a visit to the Death Wish Coffee office in upstate New York, “Whatever it is that you’re passionate about, whatever it is that you’re trying to do in this one life you get, we’re trying to fuel you to do.”

They don’t sell coffee. They don’t sell more caffeine. They don’t even sell you more energy. They sell fulfillment, the promise of a life fully lived, of your passion relentlessly pursued. They sell the ability to work incredibly hard and to leave this world a little bit better than you found it before you leave this world for good. They sell the idea that you’re gonna die, so go after the life you want … hard.

Great! So, um … how do their listeners learn how to do that stuff? They can’t just google it. Instead, they embark on a journey, led by Jeff and Death Wish, to meet people who have done this, who are equally fueled by the prospect of death, and how it shapes them and their work and passions.

The podcast even spawned two video series (spinoffs, merch, and surrounding content are usually good examples that a show is proprietary, since it’s the intellectual property — that “brand IP” I’ve mentioned — that people want. Brand IP has value beyond one delivery vehicle. Just look at the way large media brands take their core stories and characters and redistribute, repurpose, and reshape them for different mediums and products — brands like Disney, or Marvel, or Pixar, or Star Wars.)

(So Disney.)

Developing true brand IP, instead of handing out more commodities, is the key to any company of any size creating someone’s favorite show … and becoming their favorite brand.

Death Wish is not a huge company, and yet they thrive in the face of giant, well-capitalized competitors. How? Because they’ve earned something that a competitor can’t just write a check to purchase: genuine connection. They’ve taken their audience on a journey, earned significant time, earned deep trust and love. They’ve created a show capable of being someone’s favorite … and thus, a brand others call their favorite, too. (I mean, dozens of customers have gotten tattoos of the Death Wish logo or various sayings from their content.)

At the end of this post, we’ll try to make sense of how a show like The Coffee Lover’s Podcast — Yet Another commodity show — can move to the right along the Experience Spectrum and towards something more similar to Death Wish’s show. But before we get there, let’s learn about our proprietary example from the marketing world.

Marketing tech brand:

The most commodity version of our marketing tech brand’s show, Marketing Trends, was a curated roundup of news, trends, and links the team found. What would a proprietary journey look like instead? Again, we need a real show: The Loyalty Loop from marketing speaker and author Andrew Davis. (Here’s the playlist of every episode on YouTube.)

By the way, this means that, yes, I failed to find a marketing tech company that has a podcast built like a journey, or even a marketing podcast like that. So I’m turning to Andrew’s video series instead. (My podcast pick would have been HubSpot’s Weird Work, but the host left the brand for a new job, and the show has been shelved. Boo. If you find any examples, please send them my way.)

Jeez, where’s Bob when you need him most? He’s slacking off, that wand…

So, unlike a marketing show that shares easy answers to common questions, Andrew embarks on a journey in The Loyalty Loop by asking uncommon questions instead. Each episode, he rethinks the way marketing is done, especially the marketing funnel and all the traditional tactics and conventional wisdom used in funnel-focused organizations.

Some episodes, Andrew attacks the funnel directly. Other episodes, he talks about topics that, if you understand the whole journey, you clearly see how it ties together. It all adds up to a shared experience, focused on uncovering small changes with big impact.

Andrew doesn’t have all the answers, but he’s leading the quest to find some. For instance, he constructs a visual of the Loyalty Loop as a replacement for the marketing funnel. But then, each piece of the loop leads to more questions. Once he covers a single piece in one episode, he knows there are dozens more episodes that flow from that one. That’s how good journeys unfold and earn more time, trust, and love: One idea or question begets endless amounts more. Each new episode is at once an Idea Branch from a previous Inspiration Trunk and its very own Inspiration Trunk for future Idea Branches.

Questions beget questions. Episodes beget episodes. The journey unfolds.

In both cases, Jeff’s show for Death Wish Coffee and Andrew’s show about the Loyalty Loop, the hosts and the content itself are implicitly promising more to the audience than the raw asset of information. They’re promising adventure and change. They’re focused on the story of what could be.

It’s not: Here’s information. You have some now.

Instead, it’s: Over there is our destination. Here’s the jungle between us and that mountain peak. Let’s go on this journey … together.

To create someone’s favorite show, we can’t create commodity experiences. Instead, we should craft proprietary journeys. Commodity shows offer transactional value, which doesn’t earn us much time, trust, or love. But by focusing on the story of what could be, proprietary journeys become transformational experiences. That’s our aim. That’s our challenge. That’s also our opportunity.

![]()

Here, we have to set aside our two examples (coffee brand and marketing tech brand) in order to finish the entire Experience Spectrum. Then, to end this post today, we’ll bring those examples back and see where we’ve landed.

Completing the Spectrum: Moving Between Commodity and Proprietary Experiences

Moving from left to right, the audience experience changes from something highly commodified to something that’s still rather common yet aspires to be more proprietary: expertise.

To find and experience quick answers to common questions, i.e. solely the raw asset of information, people might as well google it. But when is an answer some can google more than just an answer? When it comes from an expert.

Here, the value starts to come from a broader story. It’s not just the raw asset. It’s the raw asset from someone whose story matters to you or others like you. The source of the commodity is more prominent.

Here, the value starts to come from a broader story. It’s not just the raw asset. It’s the raw asset from someone whose story matters to you or others like you. The source of the commodity is more prominent.

It’s no longer this: Here’s some gold. You have some now.

It’s this: Here’s my gold. You have some now.

Some news anchors are trusted more than others. Some marketing tips and tricks feel more valuable coming from certain marketers, perhaps individuals who are widely known. (Notoriety is often a shortcut people use to tell themselves the story that a certain source is more worthy of their time.)

In our world making podcasts, this type of experience is more about the podcaster who delivers the information to listeners, not the information itself. They aren’t some unnamed announcer giving voice to some facts. They’re a Very Respected and Smart Expert.

But we still have a problem. Knowledge itself has become a commodity, and with it, the experts who share it. Very Respected and Smart Experts are everywhere, countless to a given topic — and countless more who aren’t experts but hype and hustle their way into the public eye by convincing others they are indeed experts.

Today, the world’s information is at our fingertips. We can learn just about anything from just about anyone, all on our own, for free or at least for cheap. That ubiquity and accessibility were both unthinkable even a few decades ago. Now, it’s commonplace.

Expertise is table stakes. Simply being an expert or sharing expertise doesn’t make someone or something worthy of your significant time investment. To separate, to become someone’s favorite, and to create a truly transformational experience, the expert must bring something else to the show. (We’ll cover what those things are in the next post.)

Although it seems a bit crazy to say, even today, the expert’s knowledge has become a commodity. We aren’t at Proprietary yet. Let’s keep pushing ahead on the Experience Spectrum.

Moving further to the right, the experience is no longer about one person (the expert). Instead, it’s about a community.

To find community, someone might join a meetup or a Slack/LinkedIn/Facebook group. They might attend an event or a happy hour. Regardless of how they do it, it’s here on the spectrum that they’ve found their tribe: not one but multiple voices, not merely speaking at them but communing with them.

Sometimes, as with the examples I just listed, that happens overtly: one person joins a group and begins to interact across individuals, all the connecting arrows flowing in all directions between people. Other times, however, the community is more sensed than overtly present. For instance, on a podcast, the host might mention or talk to others in the community, whether well-known guests or their actual listeners. Maybe community is felt in the insider language and inside jokes the hosts use, without explanation. Maybe access to community is like a VIP section for listeners — they can join an email list or Slack group or exclusive event.

Regardless, the show host builds community around the show — a far more proprietary experience than merely saying smart or entertaining things to the audience. Instead, it feels like each individual is part of a larger whole.

Creating Commodities Is Pointless. Creating Community Is Powerful.

Unlike information (left-most end of the spectrum) or knowledge (one step to the right), connection is not a commodity. It’s a precious thing.

Connection is hard, connection is rare, and being the person responsible for connecting people to each other is where we can shift our experiences from commodities to something much more proprietary. In our work, we shouldn’t strive to be experts so much as connectors — of ideas, of people, of groups.

But a community, admittedly, is still only as valuable as the members inside it. That’s why there’s still one more step on the spectrum, which we already know: the journey.

Journeys feel like one group switching from interacting with each other to exploring the whole world, together. You’re not part of a community, per se. You’re part of a fellowship, in that classic Lord of the Rings interpretation. You’re one party on an adventure. When the journey unfolds through content instead of physical places, it’s not limited by geography or resources. It’s limited only by your imagination.

![]()

Looking at it now, I realize that the Experience Spectrum breaks into two distinct halves. Things on the left side of the spectrum provide a type of value that can be experienced just fine when you’re alone. Things on the right side of the spectrum provide a type of value that’s best experienced together.

Now let’s revisit our two example shows really quickly. Remember, this is only to describe what others experience. In my next post, we’ll learn what the creators actually did behind-the-scenes to change and evolve the experiences.

For now, let’s shift the shows to the right on the Experience Spectrum, starting with the coffee brand.

Coffee brand:

All the way to the left on the Experience Spectrum: The Coffee Lover’s Podcast. What people who love coffee need to know about coffee.

Here, the audience experiences interesting factoids about coffee trends, like which roasts are popular, or which tools make which type of coffee, or which brands announced various new things. There’s some value, but it’s exactly the same value found in any similar podcast. There’s no story of what could be.

The best way to experience this type of value is to simply google it. If the audience can’t read something, like for instance when they’re walking the dog or driving somewhere, then the ideal listening experience is the shortest episode possible. The best a podcaster can do if all they share are the raw facts is to condense the experience as much as possible. That’s what transactional value is all about: completing the transaction as quicky as possible. For a podcaster, if you’re stuck at this stage of the Experience Spectrum, you’re implicitly urged to simplify and shorten your content as much as possible until, eventually, you fall out of the container of a podcast entirely and start writing blog posts, which then become bulleted takeaways, which then become those chairs in The Matrix movies where a human can just download the information straight to their brain. THAT is the race to the bottom when we solely share transactional value in our content.

Thus, it becomes really hard to earn the time we need from our audience, to then earn trust and love. So let’s move further to the right on the spectrum.

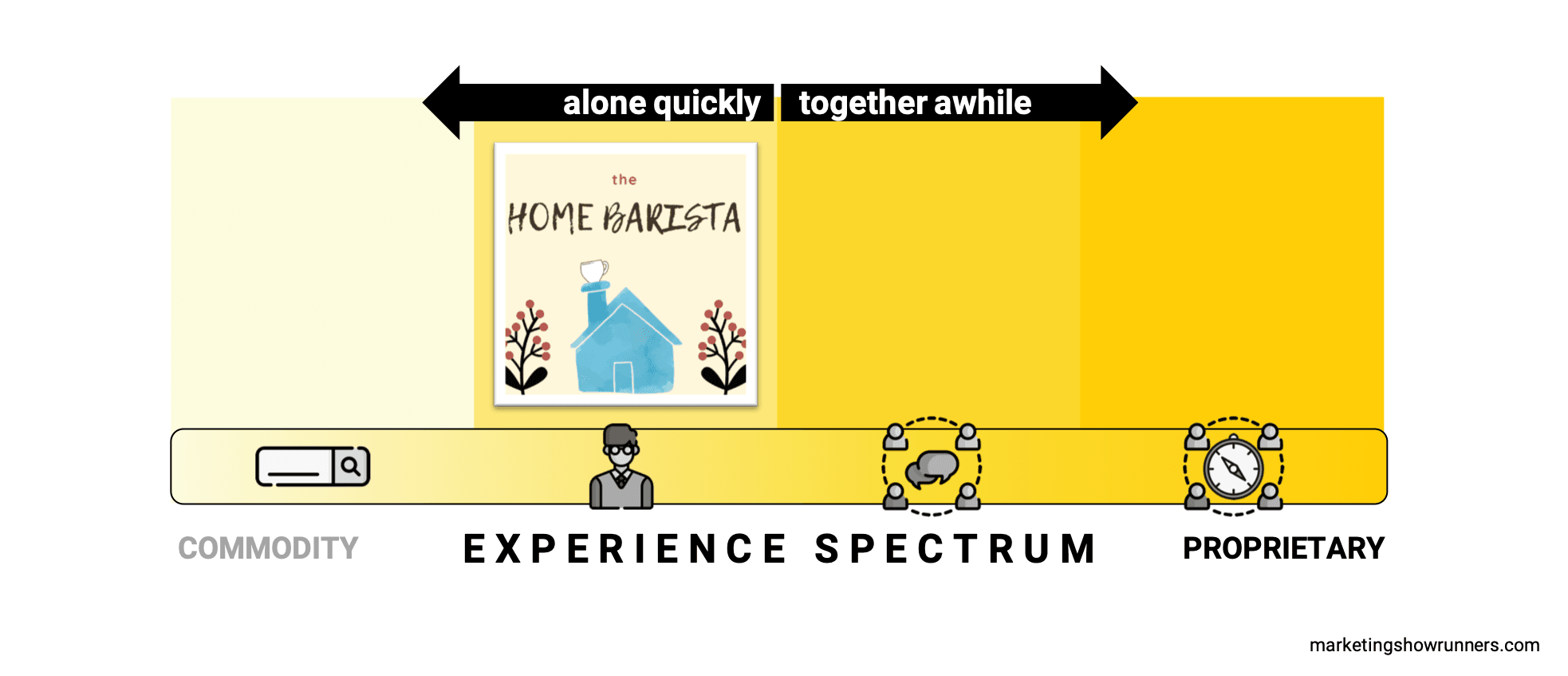

Middle-left on the Experience Spectrum: The expert-driven podcast. Let’s call our coffee brand’s version of that show The Home Barista.

Here, the audience might receive the same information they’d get on The Coffee Lover’s Podcast, with one notable exception: It’s delivered by an expert with authority (the hosts, the guests, or both). There’s now an emerging story of what could be. Maybe, the listener thinks, the facts delivered by an expert — or from this expert instead of that expert — are somehow more than just facts. They’re more correct, more timely, and more important, because the person has more expertise.

Also found on The Home Barista that wasn’t found in the previous show is some extra context surrounding the facts: expert analysis of what the facts mean, how they connect to other facts historically or presently or in the future, and/or some prescriptions of what to do next if you’re listening. How might we use the facts gathered and delivered in this episode? Well, the expert will tell you how to be a better home barista, what to do in light of this week’s news, and so on.

Listeners can still mostly google all this information, but because it’s delivered from one or more experts directly, in the profoundly intimate form of voice, listeners can have a deeper relationship with the host and the show. That feels a bit more proprietary than facts, plainly presented.

Great, we’ve taken our coffee show one step along the Experience Spectrum. Let’s do the same for the marketing tech brand.

Marketing tech brand:

All the way to the left on the Experience Spectrum: Marketing Trends, a podcast about marketing trends. (Also stuff that happened in marketing recently.)

You know what to expect from this show already, so let’s move to the right one step.

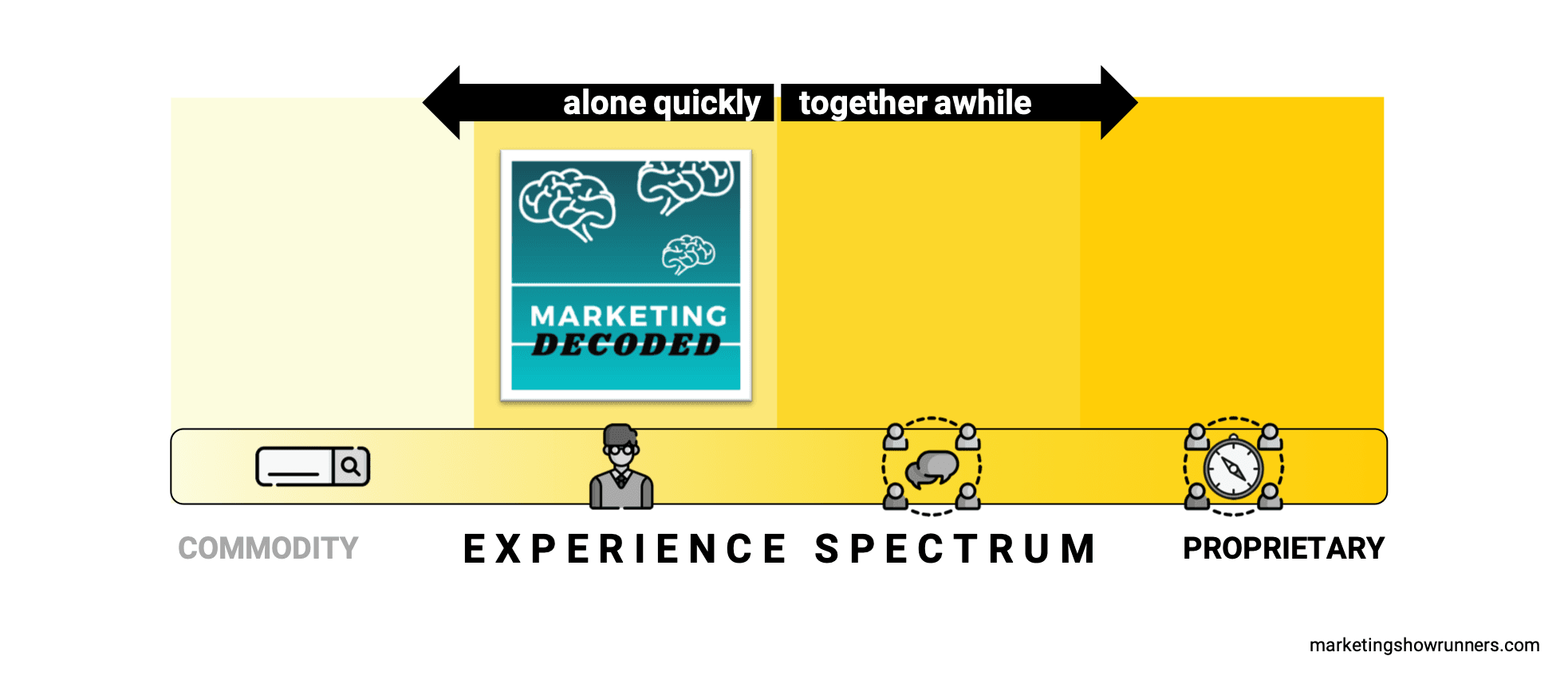

Middle-left on the Experience Spectrum: Our expert-driven podcast here might be called Marketing Decoded.

Here, the audience gets similarly curated news about trends and who is doing what around marketing, but because this is an expert-hosted show, the audience also gets some additional ideas for how all these facts fit into the broader context of what’s happening in marketing. It’s not just a description of what happened that week. It helps the audience zoom out and understand why and what it means (“So what?”).

Again, that feels a bit more proprietary and less commodified than a curated roundup of news and links.

Barf. Also? Panic. That’s how I’ve felt writing this mega-post … with two more to go.

But this is our journey after all — the reader, me, and you too, Bob. This can’t just be googled. This isn’t a commodity. But it also means making this post more entertaining so people finish it.

Feels a bit like putting a hat on a hat.

I mean, you kind of already exist solely to break things up a bit.

Yeah. It’s okay. I’m glad you’re here, even if you’re just the result of me getting exponentially weirder thanks to social distancing and my already rather odd imagination.

But this break in the action helped me realize: We’ve moved our example shows one step to the right on the Experience Spectrum. We haven’t switched from commodity to proprietary experience though. Nor do I think we can achieve that yet. There’s something missing in our exploration today that’s preventing us from proceeding:

Here’s what we still need to understand, Bob/Loudest Current Voice In My Head: What can we as creators do to move our shows across that dividing line? How can we stop creating commodity experiences and give our audiences something proprietary instead?

If the Experience Spectrum is all about how others experience what we create, then what’s our role in crafting those experiences to be transformative? Surely, we have some agency in all this? Any ideas?

No, but … thank you?

Okay, I get it: Your ideas are my ideas. Magic. Right. I’ll just pick you up with my right hand to learn another concept … and maybe then we can push the experiences of our shows all the way right.

Let’s see, what do we all most desire to understand now? Ah, right: What is our role as makers and marketers in crafting more transformative experiences for others?

Another spectrum. Okay, Bob. What’s the deal?

Another spectrum. Okay, Bob. What’s the deal?

Right, you’re right, I’m sorry, I get it: I now magically know what you know.

Okay, so, the Style Spectrum…

I’m sorry, but is that … is that a fedora?

Right. Whatever. We don’t have time. We’re almost at the end of Part 1.

So the Style Spectrum?

The Style Spectrum reveals our whole deal as podcasters, thinkers, creators, and leaders. If we’re going to understand how to move our shows beyond the commodity half of the Experience Spectrum and towards something proprietary, we first need to understand the Style Spectrum (coming up in the next post in this three-part mega-series).

The Style Spectrum is just that important, because you are just that important. You (or the team, if you work with others on the show) is the biggest and most differentiating variable present in your work compared to everywhere else. You are your unfair advantage in creating a transformational experience. The question isn’t whether a person or a team has an unfair advantage. The question is whether you’ve taken the time to identify it … and use it proactively.

So, if the Experience Spectrum is how others receive your work, then the Style Spectrum is how you deliver it. It describes the various ways your involvement changes the work for the better.

So, if the Experience Spectrum is how others receive your work, then the Style Spectrum is how you deliver it. It describes the various ways your involvement changes the work for the better.

This brings us to the second item in our three-part list of concepts, all meant to re-frame how we think about making great shows. Here’s the full list again:

1) How do others experience our show?

2) How do we personally influence that experience?

3) How do those two things combine to affect how others feel about the show? In other words, how do different types of experiences and different ways we could get involved in crafting them ultimately lead to someone declaring, “That’s my favorite podcast”?

Today, we covered #1. We now have a way to understand the types of experiences others receive from us, and which type we want to create if we want to make their favorite show. Our goal is to avoid creating anything resembling a commodity and to instead take them on a proprietary journey with us. But how? What can we do to craft that type of experience? We have to tip beyond the halfway mark of the Experience Spectrum.

That’s where we need to understand the Style Spectrum. That’s next time.

The good news? We have a magic wand to make the complexity not quite as complex. The best news? You matter. A lot. You have a huge role to play, and the skills required are things you can learn. In fact, you might already possess those skills and just need to put them into action. Either way, YOU are capable of crafting a transformational experience for your audience.

You can create their favorite show.

And you will.

![]()

Go to Part 2: The Style Spectrum ➡️

And be sure to subscribe to get each of these new ideas — plus a bonus video/story found nowhere else — every Friday morning via email. Join thousands of subscribers from brands ranging from Red Bull, Adobe, Amazon Prime Video, Mailchimp, and Salesforce, to thousands of small businesses, startups, and creators. Join the journey at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com