A Simple Visual For Crafting Amazing Podcast Intros

Here’s a question: Why are some backstories and bios of podcast guests super boring, and others gripping? Do you think it has to do with the person, and how successful they are or how well they can tell their own story? Maybe. I think something else is happening, and it’s that very same thing which can make or break any podcast episode, whether or not you interview guests.

But to understand what I mean, we first need to take a step back.

Buried beneath the complexities of any creative endeavor are simple processes, techniques, and decisions you can actually visualize. The problem is that rarely if ever do we stop our daily rush long enough to study the minutiae of the created work. This plagues our podcasts more than most projects, since podcasts suffer from this problem in two ways:

First, we become overconfident that we can recreate great moments on our show, without seeing the underlying structure of those moments. We become overconfident because we don’t have “talker’s block,” so creating a podcast feels easy. Creating an engaging podcast? Creating an original podcast? Creating your audience’s favorite podcast? That’s an entirely different matter. We can’t just talk through things. We have to understand the techniques and processes that shape moments that prompt listenership and word-of-mouth.

The second issue is that amazing shows often feel “big,” like the creators pulled off the impossible. Indeed, a show has a kind of elevated feel to it, doesn’t it? It’s not a single piece, like this article. It’s a show after all. They’ve done something big. Can we? Not unless we see a show for what it is: the sum total of lots of small moments, all strung together, all of which can be practiced and learned. Creativity never means “big.” It’s become the single biggest barrier to doing great work today: We think creativity means big. It doesn’t. Zoom in, and you’ll find all kinds of tiny choices anyone could make. The real trick is making those choices consciously and consistently such that they become second nature to you.

So now we arrive back where we began: Buried under complexities are simple things we can visualize in order to access them, then master them. And given the nature of your show, few things are more important to visualize, access, and master than how you open your episodes.

Most podcasts open with a whimper. The best shows — across any medium, audio or otherwise — use those precious first few seconds or minutes to do what episode opens are for: grip the audience. You are purchasing future attention. You are earning the right to keep going. Don’t blow it by adding a bunch of boring housekeeping, meaningless filler statements (“I’m so excited!”), or redundant and lengthy introductions of the guest’s worthiness to appear on the show.

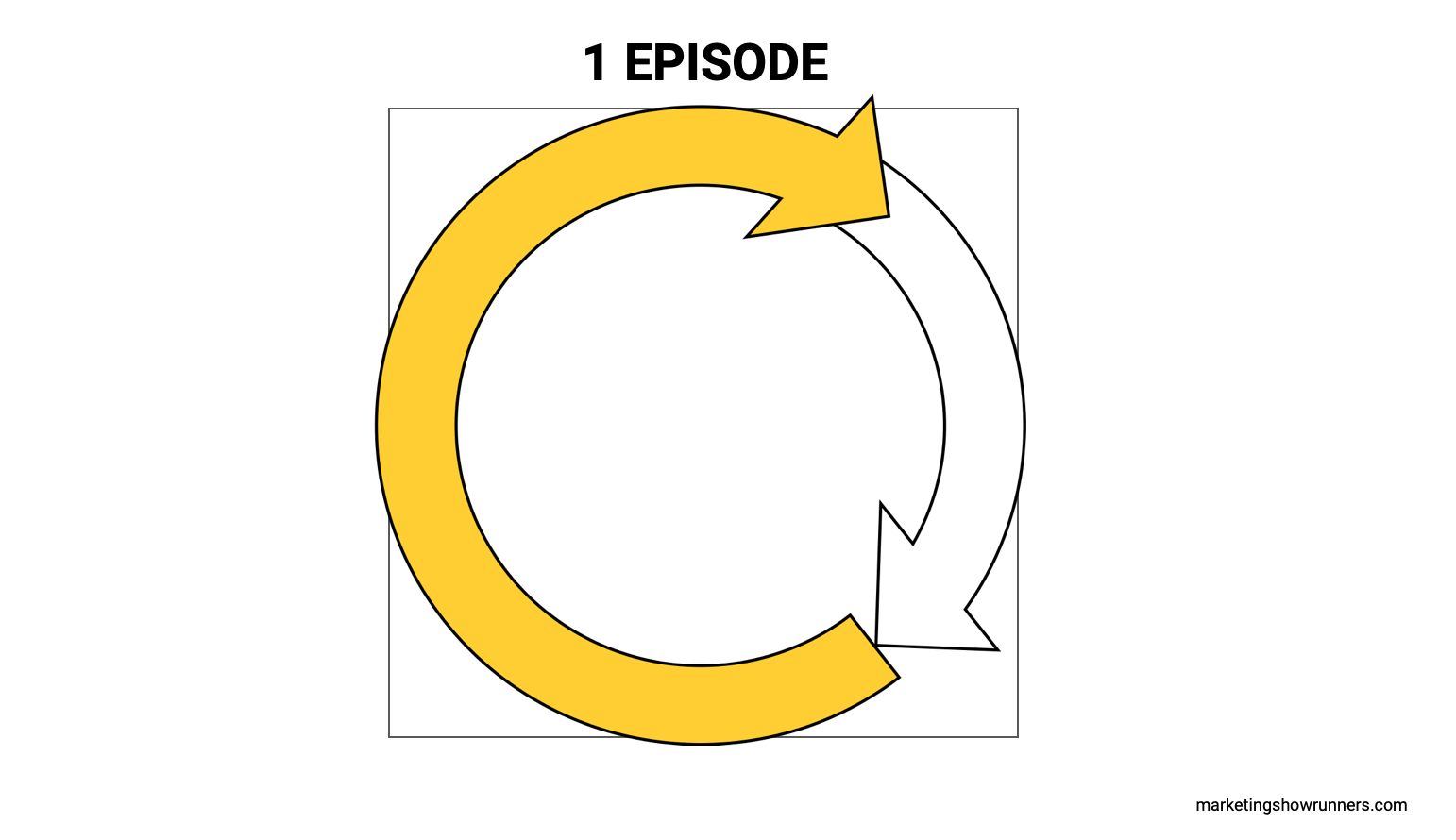

To start an episode, visualize what you’re doing: revving up the audience such that they want to speed ahead. They’re eager to listen. And as I’ve written about in the 6 types of open loops, the most effective way to do this is called the “episode loop.” It looks like this:

If open loops are techniques that raise anticipation for future closure, episode loops are a type of open loop which raises anticipation for future closure within that one episode. (If the very idea of open loops are new to you, please read the entire introduction. If you do nothing besides learn about that concept, you will create a radically better experience for your audience — one they stick with for hours instead of minutes.)

An episode loop would be like opening your episode with the first few details of a story, then leaving people hanging to provide closure by the end. Another type of episode loop is to ask several open-ended questions at the beginning, the answers to which will provided to listeners by the episode’s end.

“Ever notice that most podcasts open their episodes with a whimper, instead of gripping you? Why is that? Why are boring intros the norm? What’s happening in our brains that causes us to play it safe? And what should we do instead? Today, we talk to a psychologist, a marketer, and a podcaster who can answer these questions. Ironically, that’s all the same person.”

Here, I’ve provided you with several questions you may want answers to — if I know my audience, that is — and even a statement which prompts you to ask an implicit question: Wait, so WHO is this person? (Side note: Never tease something inside the episode which is already given away by the episode’s title or description/show notes. That’s like playing peek-a-boo with an adult friend. Um, dude? I can still see you. You just covered your face with your hands…)

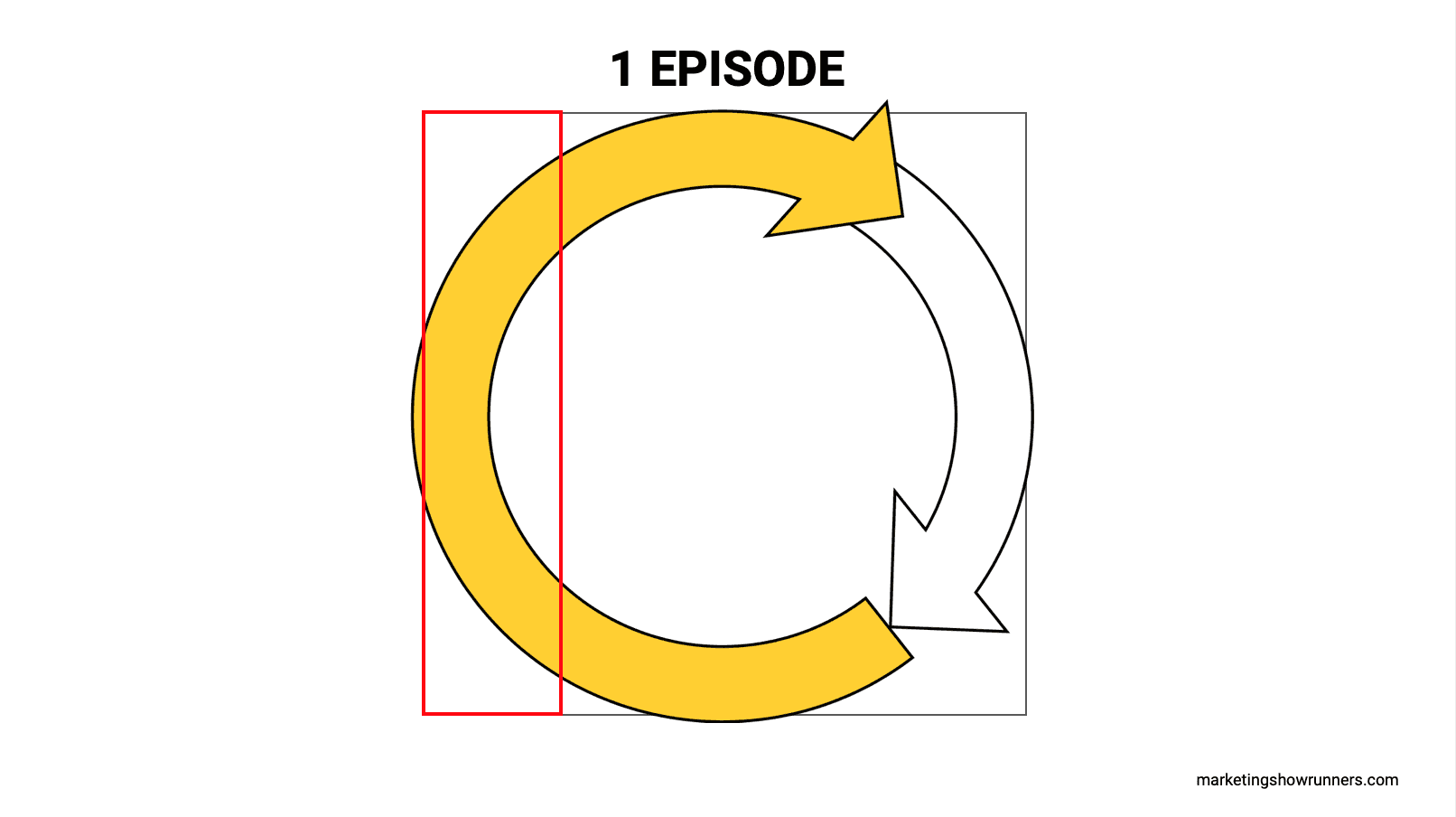

So, if open loops hold attention and prompt listenership and episode loops — specifically, opening an episode loop — are the best way to start your episode, then how can we predictably, consistently execute this technique? We know that an episode loop can be visualized (see image above). What I really want to know next is what happens here, in this tiny moment:

What are we saying or doing within that first micro-moment, those first few seconds or minutes, that not only open the loop but advance people forward into the episode? After all, we can easily raise anticipation with things like open-ended questions or stories we promise to finish later. That’s not hard to grasp. What might feel elusive is what to say once you’ve raised intrigue.

But to understand what I mean, we first need to take a step back.

(Spoiler alert: That sentence, used twice in this post now, is the answer.)

It’s a common cliche among podcasters, perhaps, but hosts often start by raising intrigue about a story or concept, then “step back” to understand foundational ideas, backstories, or context the listener needs to hear to understand the rest of the episode. In other words, to close the loop in a satisfying way the listener can follow, the host first needs to deliver some facts. The problem is, facts are boring. Context is bland. Guest bios are insufferable.

The other problem is, all that stuff is where most of us tend to begin our episodes, which hurts the experience. That’s why so many hosts open shows by summarizing a guest’s bio. They assume that the logical place to start is the best place to start. But to ensure audiences want to stick around for everything you have to say, you first need to place today’s guest or topic or any facts/backstory/context/research … into context.

Here’s an easy way to remember this:

Show audiences how facts they need to know will help them understand what they want to know.

You want to know how a business advice show will transform your company. But to understand that, you need to understand how today’s guest arrived at their advice, so here’s their bio…

You want to know what the future of NBA basketball will be. But to understand that, you need to understand the last three decades and how it shaped the game, so here’s some data on scoring and shooting…

You want to know how to better open your podcast episodes. But to understand that, you need to understand how the current approach to intros are broken, so here’s how the usual episode begins…

You WANT to know this, right? But before you do, there’s something you NEED to know first.

Let’s take a step back.

What a simple but arresting way to open an episode. The facts switch from something flat or boring into something urgent. Some nice-to-know content now becomes must-know material.

As showrunners, hosts, and producers, we’re in the business of delivering episodes that push people, challenge them, grip them, and change them. Anything else just panders. We refuse to ship commodity episodes, easily copied, easily forgotten. But that means we often find ourselves in the unenviable position of sharing information that we know they need … but they may prefer to skip. But when we deliver it in the context of what they want — and we start by making it clear that’s what we’re doing — they’ll agree to listen. In other words, if they know how how what WE need to say gets them what THEY want to get, they’ll happily listen. If they don’t understand that? It’s boring housekeeping, meandering summaries or backstories, and flat facts they’d prefer to skip.

Ugh.

Let’s look at an example, then visualize the technique so we can repeat it.

The Nod is a podcast launched by Gimlet Media, which has since been moved to the short-form video platform Quibi. On a recent episode of 3 Clips, I dissected a clip from The Nod which exemplifies this idea of inserting “need-to-know” facts inside “want-to-know” material.

The Nod “tells you stories about Black life that you won’t see anywhere else. Five days a week, hosts Brittany and Eric bring their love and passion for Black culture to celebrate its biggest moments and reveal its most under-explored corners.” For instance, they might explore the HBO show Watchmen, through the lens of Black culture. You, the listener, arrive to hear them interpret the show, but summarize it … but you do need a bit of summary, a bit of backstory, for the rest of the episode to make sense.

Enter host Eric Eddings on a 2019 episode of The Nod, talking about Watchmen. Here’s what he says to his listeners (I’m paraphrasing):

There are tons of superhero TV shows and movies out there, used to help understand society’s problems and how we think about fixing them, and I watch all that stuff. But Watchmen puts that on steroids.

The open loops have been established: The very premise of the show (aka their “show loop”) establishes a consistent open loop for us (how will today’s topic reveal something about Black culture we hadn’t considered?). But then, the words above help Eric establish an episode loop. We want to know how Watchmen takes common superhero tropes and puts them on steroids. Our assumption is that’s what this episode will explore. We will receive closure by the end. The loop will close.

The next thing Eric says, however, is the revealing part. I’ve added that in bold below:

There are tons of superhero TV shows and movies out there, used to help understand society’s problems and how we think about fixing them, and I watch all that stuff. But Watchmen puts that on steroids. But to understand that, you first need a bit of backstory.

(He then explains the basic premise of the show, Watchmen.)

Brilliant! So simple, so easy to miss, but brilliant. Eric places the need-to-know facts in the context of the want-to-know material. In other words, the straightforward stuff sits neatly inside the tantalizing open loop. The entire experience is enhanced.

There are countless ways we could open our episodes, but we can plot out some of the best, and easiest to copy, such that we can repeat them and modify them to our shows, too. Here’s how I’d plot them out.

1) Start with a status quo. This is the first piece of any story, whether or not you consider your episodes narratives. Something is happening, or something is assumed. At the top of this post, I asked about the status quo. Why are some backstories and bios of podcast guests super boring, and others gripping?

2) Introduce the conflict. What tension or challenge to the status quo can you share with audiences? This changes what they think they knew. It throws them into some uncertainty, which of course they now want resolved. (That’s why open-ended questions are so powerful in your intros, provided they’re questions audiences genuinely don’t know the answer to but wish to hear it: instant uncertainty, instant desire for closure.)

In Eric’s case, the conflict he introduces is the idea that Watchmen takes the status quo (tons of superhero media already exists) and “puts it on steroids.” We now crave the third part of the story, which normally would be this:

3) Resolution. Reveal the answer, the better way, the new understanding. Here’s how to open a podcast to make even the most bland bios seem gripping. Here’s how Watchmen puts superhero tropes on steroids. Here’s how this one TV show reveals something about Black culture you hadn’t considered.

Nice little arc, and that’s how stories work. But arriving so quickly to that resolution means the episode is over. You’ve satisfied the listener’s curiosity, providing closure to the open loop created by the conflict being introduced. (This is why summarizing everything in the intro is a bad way to open — it removes the need to keep listening.) Thus, what Eric did, and what great show opens often do, is interrupt the story flow by “stepping back,” then resuming the flow. That’s how they craft compelling intros.

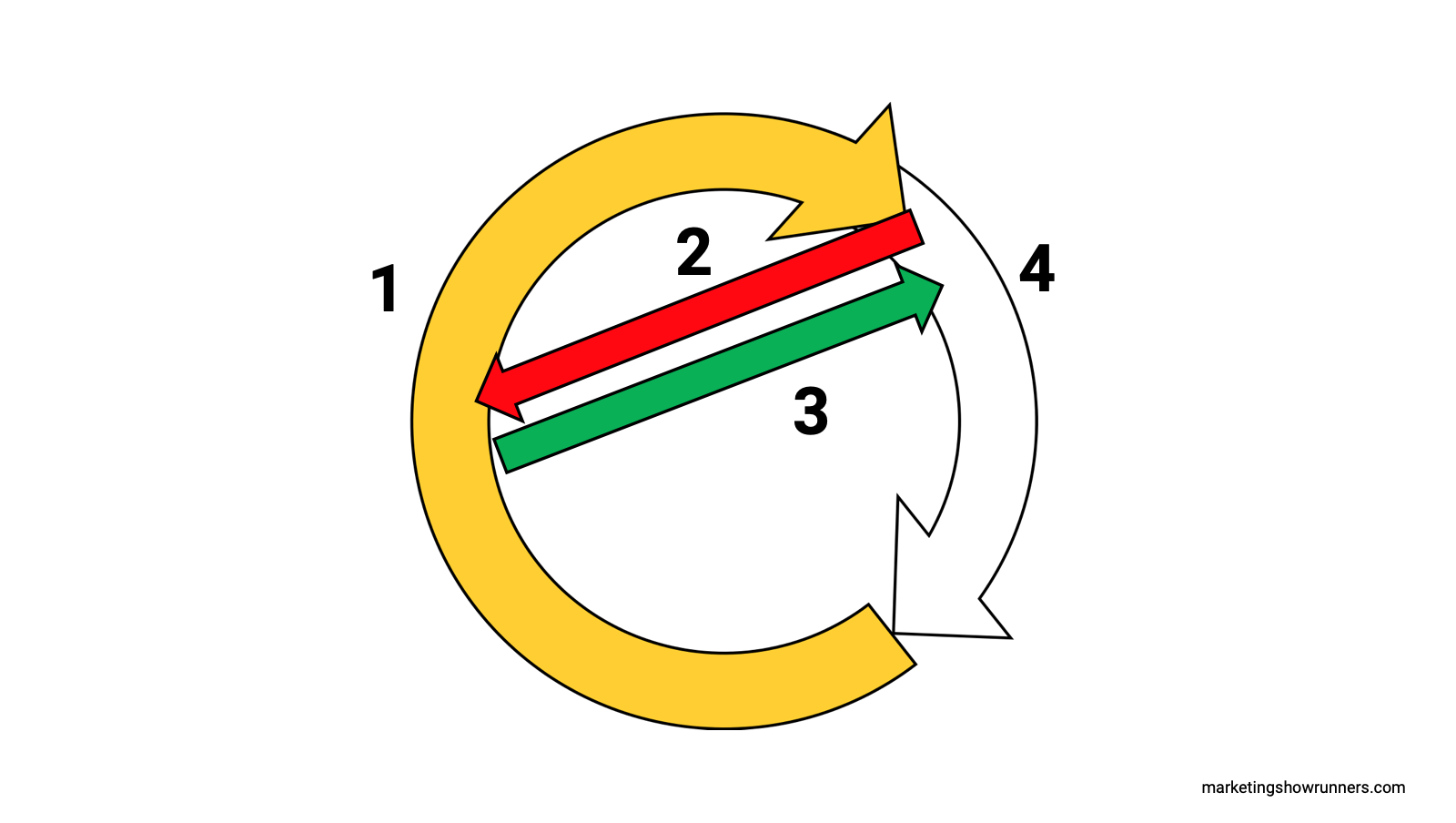

It looks like this:

Number 1 (the yellow arrow) represents the opening of the loop. Here’s the status quo, and the conflict. Here are the questions we’re asking, or the things we want to know. The listener now anticipates closure (the white arrow), but before you get there, you need to take a step back.

Number 2 is you saying, “Hold on, hold on: I know you really want to close this loop, but before we can do so, let’s go back to the beginning, to history, to the backstory, to the facts — to something you NEED to hear. Okay, now that you’ve heard that, let’s head back to the regular flow (#3) and close that loop (#4).”

1. I’m promising you something. You want that something.

2. To get that something, we have to back up a bit.

3. Once we do, we can go back to where we left off.

4. The rest of our time together provides you the closure you seek. I deliver on the thing I promise, the thing you want.

You can open your episodes in countless different ways, but the only consistent trait that makes for arresting opens is that they prompt future listenership. The only way to prompt future listenership is to promise to deliver something they want first. Don’t start with the logical backstory or context, even though it does indeed feel logical. Start with the emotional thing (what they want). Then, that gives you permission to go back to the logic, to the facts, to the backstory, and begin to deliver the step-by-step flow of the story or interview.

Remember: How you start determines whether or not anyone wants to finish. And isn’t that the entire point of your episode?

You can listen to the episode of 3 Clips where I analyze this technique by examining The Nod. That’s here. Or subscribe below to get ideas like this emailed to you every Friday morning.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com