Radically Improve Your Show and Episode Content: The 6 Types of Open Loops to Hold Attention

We’re on a weekly journey to understand what it takes to make someone’s favorite podcast. You can get each new idea in your inbox, plus a bonus video found nowhere else, every Friday. Subscribe free to join creative minds from Red Bull, Amazon Prime Video, the BBC, the NY Times, Mailchimp, Salesforce, Shopify, Adobe, and thousands of small businesses and startups.

![]()

Almost every decision we make as hosts and producers becomes clearer when we remember two things: why we’re making a show, and how that goal is achieved.

So why do we make shows? Well, lots of reasons. We want to explore something more deeply in a world trending shallow. We want to find and share our voices as teachers and creators. We want to make a difference and, together with the community that forms around the show, we can shift the culture for the better. Also? We make shows because it’s just plain fun.

But I think there’s one overriding purpose to a show, one core “why” to this type of project. To quote sound design wizard and former 3 Clips guest Richard Parks, creator/host of Richard’s Famous Food Podcast, “Why does anyone do anything?!” (He uses that as a recurring catchphrase in his show.)

Why do we as makers and marketers do anything? To earn trust and love. Period. We want our creations to make a difference and to matter. That’s the simple truth of it.

The thing is, none of that happens without others investing serious time with us and our work. Trust and love don’t happen instantly through a single list article a reader finds on Google. (Marketers, every time: “Rapport building phase complete! Sell them! Sell them! Pop-ups! Slide-ins! Automated follow-ups! ATTACK! ATTACK!”)

Ugh. Nope. Not how humans work, my friend. But you already know that. You’re reading this article.

So, if we remember what it’s like to be humans, we never forget that crucial ingredient needed to form a bond with something or someone else: time.

Fortunately, shows are vehicles built expressly to hold attention over time and create a deeper relationship. What is a show if not a single project, delivered over time? Is it really a show if they only launched one episode? That’s not an episode. That’s the whole project in that case.

So if shows are vehicles for earning trust and love, because shows are built specifically to hold attention over time, then we have a sort of Golden Rule to our work as showrunners: Get them to the end.

Whatever you do, ensure that the choices you make are pressed through that same mental filter. How is what we’re doing improving our chances of getting our listeners or viewers to the end? The end of your episodes. The end of your series. The end goal of your interaction together — trust and love.

Why do we create shows? To earn trust and love. How do we do that? We have to get them to the end, because trust and love are earned over time. If we do something worthy of staying with, not just arriving to, then we’re doing our jobs. Great marketing isn’t about who arrives. It’s about who stays.

Get them to the end.

There’s no shortcut, no hack, no algorithm to game here. It’s all about providing the best experience possible. If we want people to spend 10, 30, 45 minutes with us, several times per month, then we have to deliver a better experience.

(Here’s a tool to guide you in doing that: The Experience Spectrum.)

We know why we do this stuff. We know how the core goal is achieved. So, um … what can we do to make it happen? What do we control inside our shows such that we get people to the end so we can earn trust and love?

Open loops.

What Are Open Loops?

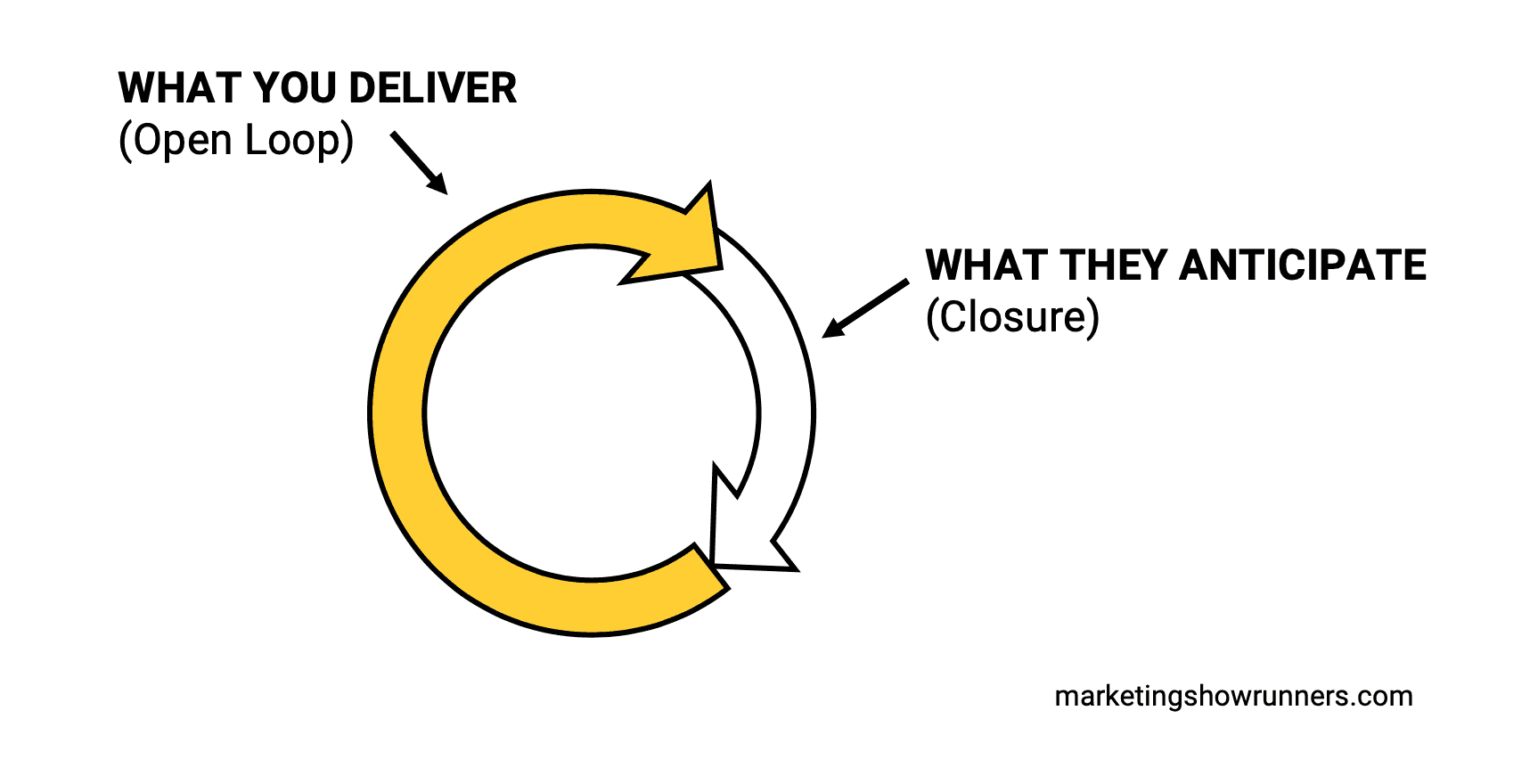

Open loops are teasers that keep audiences interested and engaged over time. They’re a type of production technique which can be planned ahead of time or executed in the moment which prompts continued attention from an audience.

“I stepped outside of my house and looked down the street and saw something I didn’t expect.”

That’s an open loop. The reason the loop is open is, of course, the missing detail of what I saw down the street.

Now, unlike purely hyping something in an empty way, and unlike slogans and other advertising descriptions for the value we offer, open loops actually begin to deliver a little bit of value, before leaving something unanswered or unresolved … until later. When we experience something like that (e.g. a sequence of events which lacks the final conclusion of it all), our brains go, “Wow, I could reaaally use some closure right now.” That prompts you to push forward and seek that conclusion. On a podcast, that means we keep listening.

Why Do Open Loops Work?

Arguably, the most powerful tool at a storyteller’s disposal is the ability to create tension. That might be an obvious example of tension (like a bad guy marching into town, or a disagreement between individuals that strains their relationship). But “tension” can also mean a contradiction, whether implied (because the storyteller says something that challenges your current assumptions) or overtly stated (the storyteller says, “I thought it was one thing. However, I discovered it was this other thing.”) Even a feeling that something is missing, like a break in the action, can prompt our brains to go wild with desire for closure. (“I went downstairs, poured my coffee into my usual mug, and then read the words along the side of the mug that I read every morning.” Nothing major happened, and yet I want to know: What were those words?!)

As human beings, we crave closure. (Very Ron Burgundy Voice). It’s science. Your brain goes, “Wait … finish that! Tell me! What happened next?! Whether we’re hearing someone’s advice or we’re listening to a narrative unfold, our desire for closure is visceral. It’s tough to feel any other way besides interested. Done right, an open loop evolves something that’s nice to know into something they need to know — and thus, on a podcast, they need to keep listening. Imagine that future for your show: People don’t just want to listen. They need to listen.

That’s how badly we crave closure as people. The desire turns us into toddlers stamping our feet, flinging ourselves to the floor, demanding that we get what we want. Because it doesn’t feel like something we want. It’s something we need.

In short, when a loop begins to open, we desperately need to see it closed.

This is a superpower, and as with any great power, we have a responsibility to use it well, in service to others. Later in this post, we’ll talk about some ways to tactfully use open loops such that you don’t over-hype the work, devolving into a talking clickbait headline. (That’s the most abused, awful type of open loop right now.)

How to Think, Write, and Speak in Open Loops

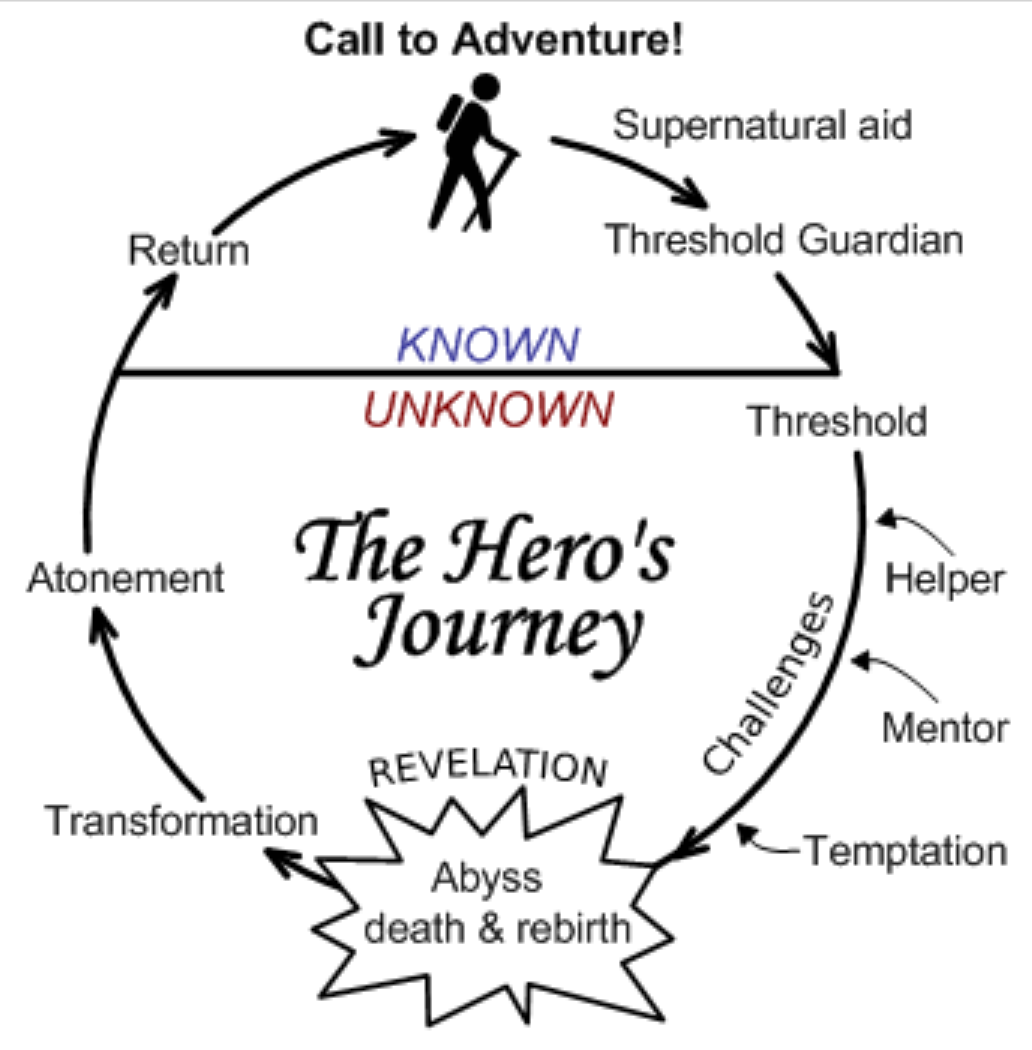

As creators, we sometimes refer to stories as “story lines.” But really, to tell more effective stories — or just to deliver a more engaging experience, even if we don’t share narratives — we should focus on story loops, not story lines. Whereas a line moves forever away from its origin, a great story must return to the original idea or question to provide closure. We can see this among some of the more widely used story structures, like Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey:

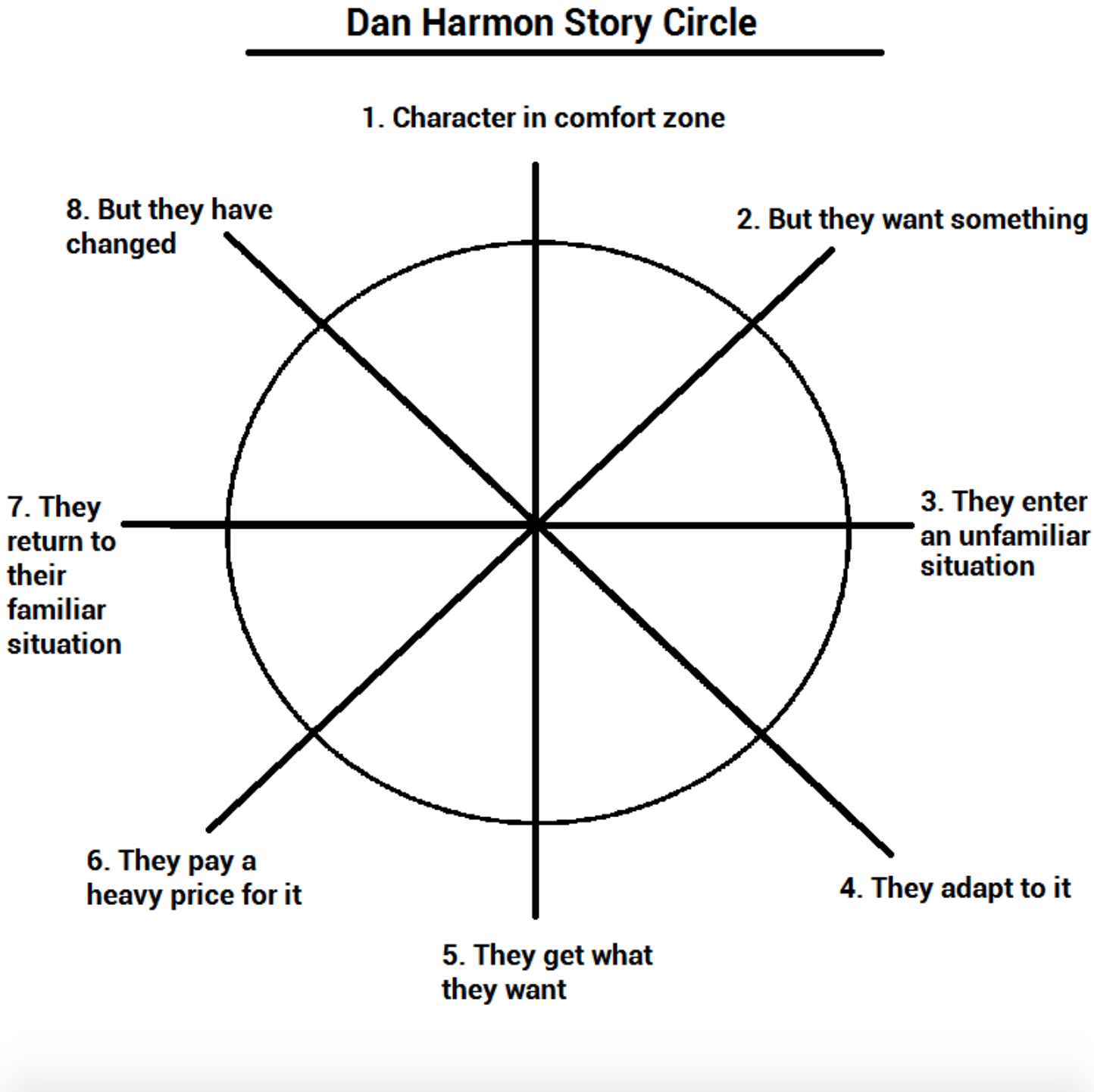

Showrunner Dan Harmon, creator of Community and Rick and Morty, uses something he calls the Story Circle:

In a past post, we looked at a process for developing stronger show premises, and we used a heuristic called the One Simple Story (OSS). The OSS is the most compressed story possible, meant to provide a kind of north star you can use to align all your content and marketing, regardless of the specific project or owner. It’s all molded by the OSS, and it all must support that one story. As such, the OSS is the quickest way to open a loop, then close it.

The OSS runs like this: Status Quo >> Conflict >> Resolution.

1. Status Quo: Share a statement of fact about what the subject of the story is going through. For many brands, the “subject” of the OSS is the customer. For a specific story about one person, however, you can also apply the OSS. Here’s one Status Quo example for each case — all customers as the collective protagonist, followed by one person as the protagonist: “For years, marketers ran a similar playbook, doing X, Y, and Z.” // “Michelle was chief of medicine, and she loved her job.”

It’s just a statement of fact. No story. No open loop. Next, let’s open that loop…

2. Conflict: Introduce some tension or uncertainty to the status quo. (“But then, along came the internet, and consumers finally had the power to navigate around crappy marketing.” // “Then, the pandemic hit, and Michelle faced some tough choices — all of which had to be made without the usual processes she had used for years.”)

The loop is now open. What will happen next?

3. Resolution: This is the closure we all crave, which then closes the loop. It answers the questions previously on our minds during the conflict section.

What does marketing look like now? (“Brands have to focus more on affinity, not awareness, creating experiences others choose and spend time with, not interruptions that force messages into their lives.”)

How will Michelle handle decision-making during a pandemic? (“Michelle did X, Y, and Z, and in doing so, she created what’s now used by all hospitals during widespread emergencies: the Pandemic Response System. She found a way to replace the paperwork-laden process in favor of quicker, doctor-led, and more patient-centric decision makiing.”)

(Just to be sensitive to the topic, a caveat that I completely made up the Michelle example and its terminology.)

When you tell a story as short as the OSS, the open loop is created in the early moments, which the latter portion of the story then closes, and closes quickly. Anything you create as a brand or individual in support of the OSS should rely on that similar story, whether overtly stated or just implied, as what you create is thematically related. The OSS, as the name implies, is a way to create an open loop in everything you make, in simple fashion. But our projects are just informed by the OSS. They aren’t usually so simple. Most things, like our shows, start to get complex. What do we do then?

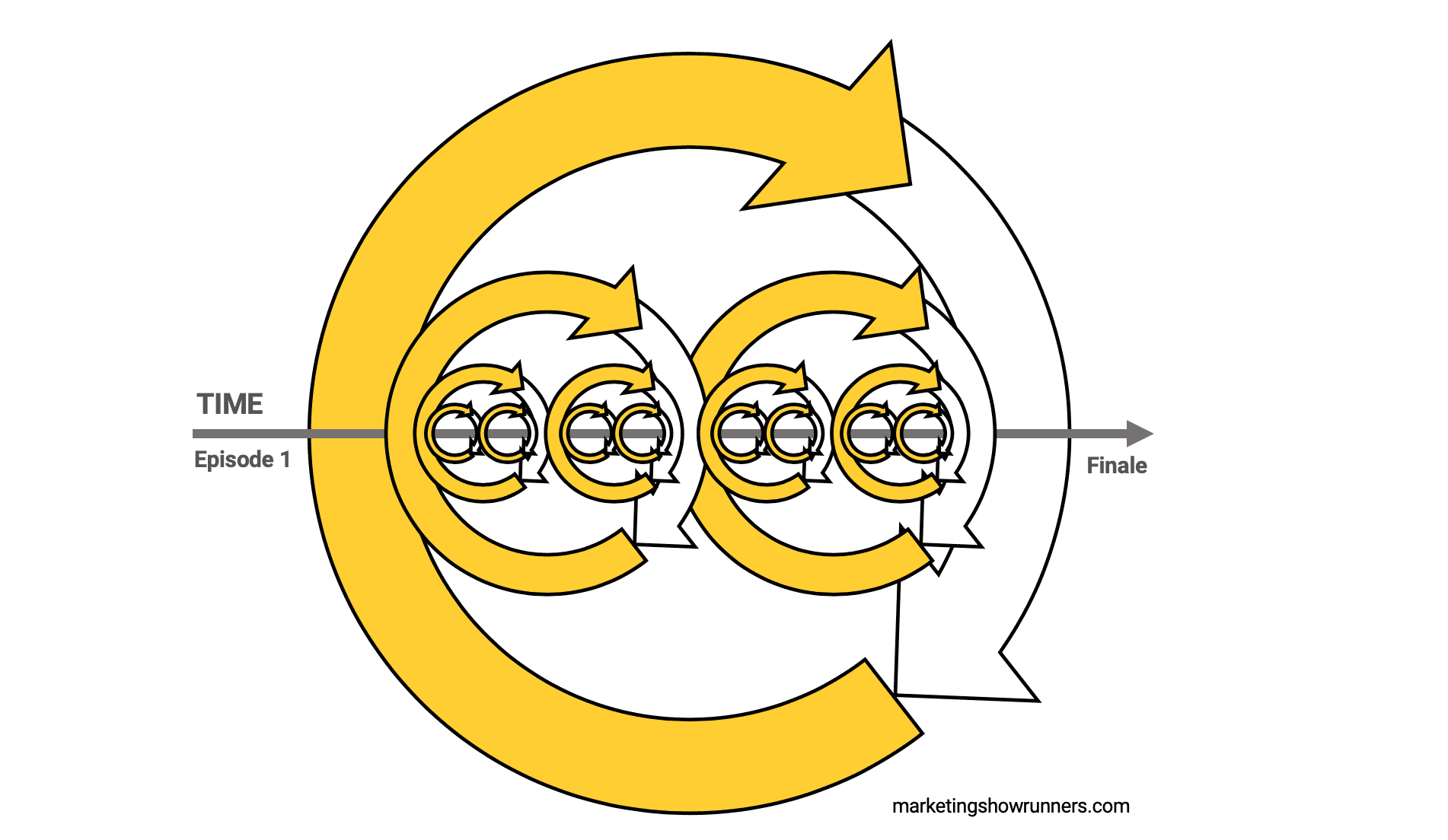

Well, what do showrunners and writers do on an incredibly complicated show, like Game of Thrones?

When you do something that involved, which also gets delivered across a long period of time (in this case, 10 years), you start to create tons of open loops, all layered on top of each other. Some of them last the entire show, some last across seasons, some across a few episodes, and some mere minutes inside one episode. Great shows create this constant opening and closing of loops. Imagine it like constant, rolling waves in the ocean, with some things creating intrigue, and some things resolving it. On more dramatic, intense shows, the ocean starts to feel really choppy at times.

As viewers or listeners, you don’t often notice when you’re experiencing an open loop. You just feel consistently interested. You feel the need to keep listening.

Despite the complexity of adding in lots and lots of open loops over time, the creators of a show — you and me included — must remain aware of which loops we’ve opened so we don’t leave the audience feeling frustrated. They crave closure. We must deliver. (You wouldn’t want to hype how great an interview guest is, before playing an interview with someone who is clearly nervous, unsure of their answers, and not overly helpful to hear talk. In the hyping process, you opened a loop. Why are they so great? What do they sound like? When you fail to deliver a satisfying payoff to that hype, the audience is frustrating. It’s not purely because the guest was bad. It’s because the anticipation you created was not matched by the closure.)

Let’s push ahead with Game of Thrones as our example for a moment and talk about this delicate balance between opening loops (easy to do) and closing them in satisfying ways (hard to do).

The Fine Line Between Fulfilling and Frustrating Episodes

We can’t stand when something is left unresolved, and so failure to close a loop can lead to frustration among your audience. To some extent, there is only one open loop across anything and everything we consume: How will this end? You start anything — a blog post, a podcast, a video, a movie, a book — and sometimes, you crave an answer to that one big question so badly that you’ll stick with the content even if you dislike it. Why are you reading that book that you decided 4 chapters ago wasn’t that great? Because, well, you started it, and so you might as well see how it ends. That’s how much we crave closure. That’s how frustrated we feel when something is unresolved.

However, as a creator, you can also frustrate your audience even when you have provided closure — if the closure doesn’t match the initial logic and intensity of the open loop.

When closure doesn’t match the initial logic, it causes frustration because the story makes no sense, and audiences are left grappling. (This is why surprise twists are either awful, or really awesome. When they work, they really, truly work, because you didn’t expect something. But the typical attempt is terrible, because it runs counter to what the audience is anticipating, thus frustrating them. Even for twists that work well, you’ll probably find tons of vocal critics. Those are the people who preferred to receive the logical next moment, not the surprise one.)

If Game of Thrones suddenly introduced, oh I don’t know, Arnold Schwarzenegger as the Terminator??? That would have broken the logic set up by the initial story. In any good fantasy, the early moments often establish the rules that govern that world. Yes, magic and dragons and walking dead people can exist in Thrones. But what was never established was the presence of advanced technology, nor the fact that Westeros exists in the same universe as any other fictional world, like that of Arnold’s Terminator. So, yes, Thrones is a fantasy, but even in the world of the make believe, not just any detail is accepted by the audience. It has to flow logically from the setup, the opening of the loop. Now imagine how easy it can be for us non-fiction showrunners to slip out of our logical setups to provide conclusions that feel out of place.

The closure you provide to any open-ended question or early sequence of a narrative should match the early logic you establish. When it doesn’t, the audience can get frustrated. What’s promised must be delivered. What’s anticipated must be received.

(Shoot, I could have written for Thrones…)

Audiences will be frustrated if your show provides answers or finishes stories that don’t match the logic initiated by the opening of a loop. But what about that other part, the intensity of the intrigue people feel?

If you build up, say, one big question as the most crucial thing your show will explore, but then the answer to that question later in the content is obvious, widely known, too complicated to understand, or too oversimplified to be helpful, then you essentially over-promised and under-delivered. That’s a classic sales mistake. It’s also an easy showrunning mistake. Don’t hype up what doesn’t eventually deliver on the hype. The reason we all hate clickbait headlines isn’t that they promise something mind-blowing. It’s that they don’t deliver on that promise. They promise fire when all they really ever give us is smoke.

This is why so many people had a problem with the end of Game of Thrones when Bran Stark ended up as the ruler of Westeros. One of the biggest open loops (i.e. the most intense) created by the very name of the show was who would sit on the throne by the end. Who will win this game of thrones? That’s a massive question, crucial to the intrigue of the entire show and many of its sub-plots and character arcs. People spent 10 years wondering that, feeling the intrigue of that open loop. It was closed with something that just didn’t match the intensity. Bran was a supporting character who didn’t appear in every episode, nor even in one entire season, and too many questions remained about his fictional powers to fully appreciate him.

Viewers felt the intensity of that open loop because the question was so big and so crucial to the theme of the show (and remained unresolved for so long). Viewers did not feel the payoff warranted that level of intrigue. The showrunners would have avoided so much backlash and provided a more satisfying sense of closure if they’d made Bran a more central figure and explored his mystical powers more fully. Unfortunately for the legacy of the show, they failed to provide satisfying closure on this particular (and critical) story loop.

All this just illustrates the power of the open loop in delighting (or frustrating) an audience. A show is a complicated collection of macro and micro loops that open and close at various times, and we’d be wise to make that a conscious, planned process. Doing so helps us craft an experience that honors the Golden Rule: get them to the end.

Macro vs. Micro Open Loops

Most of the open loops an audience experiences in any show are very small and quickly closed. The host asks a guest a question, then the guest answers it. If the question was intriguing enough, people feel some intrigue. If the answer matches that intrigue, the audience feels that tiny, addicting sensation of achievement in their brains when we receive closure, and thus the show’s host has now “purchased” more attention from the audience. They deem the show worthy to stick with a bit longer. They want that feeling again. Failing to provide compelling questions or payoffs to those open loops (answers to the questions) will result in audience churn, if not immediately, then over a few consecutive moments of open loops failing to deliver satisfying feelings of closure.

It’s one thing to ask a bad question or receive a bad answer. It’s another thing to create five minutes of flat audio with zero intrigue and zero satisfying feelings of closure.

Interview questions and answers are small loops. We can call those micro open loops. They open and close quickly. Even in a grand endeavor like Thrones, many of the open loops are similarly very small and quickly closed. Who will win this battle in this episode? (Minutes later: The good guys won.) Will Jon Snow kill this guy he just clashed swords with? (Seconds later: Yes, that nameless soldier was unimportant to the story. Jon Snow beat him easily en route to facing the real villain in this battle.)

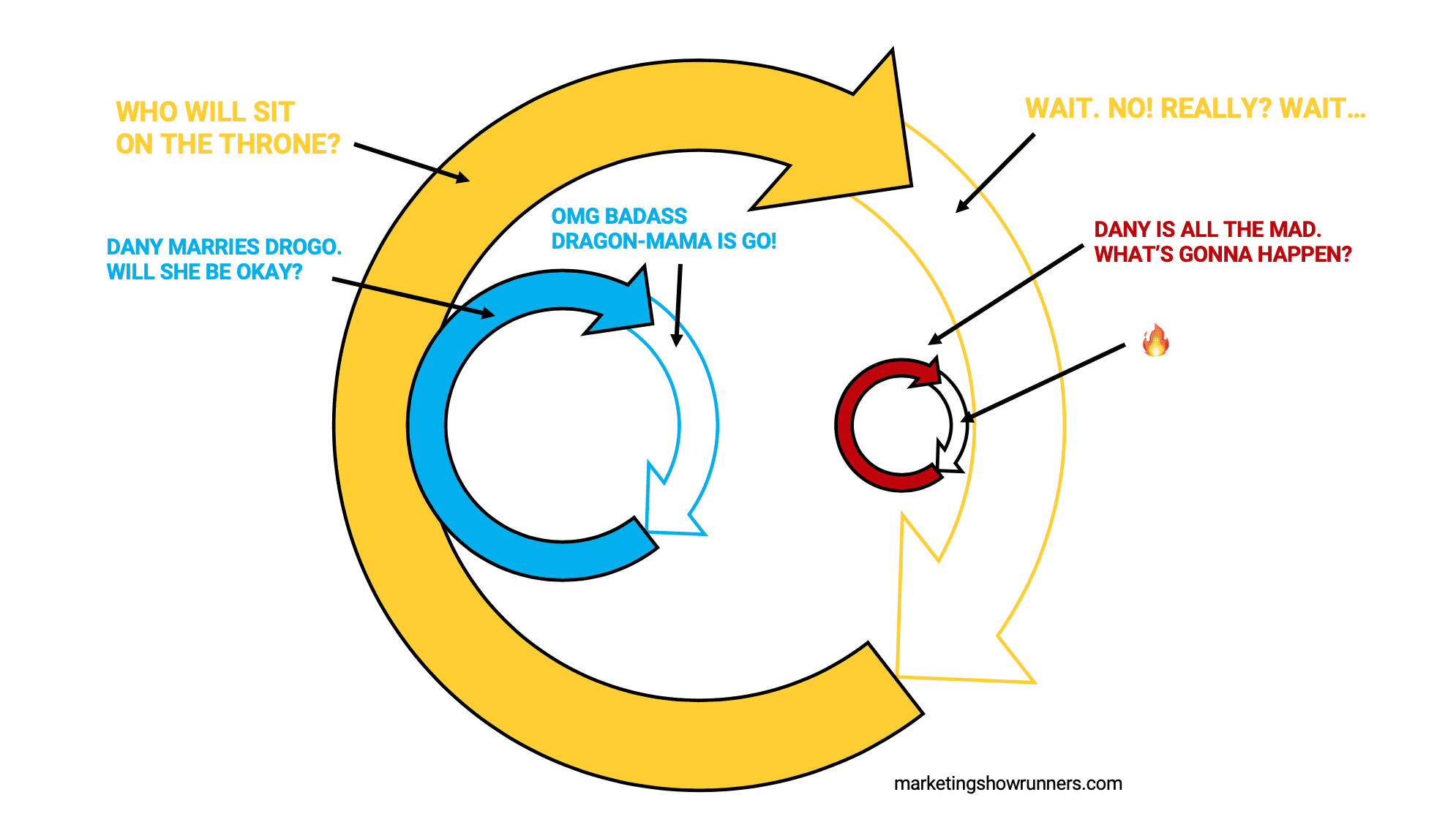

But Thrones also provides some larger, longer-lasting loops. Let’s call those macro open loops. Some lasted most or all of the show. (Who will sit on the throne? Who wins the battle against the army of the dead?) Some were medium-sized loops that lasted for a few seasons or episodes. (Who is Jon Snow’s real mother? How will Dany cross the Narrow Sea?)

But, again, most open loops were so small or so embedded in the natural way we perceived the show that we never paused to consider what the writers were doing — we merely enjoyed the show. But make no mistake, it was carefully planned by their team. When a woman walks onto camera for the first time, your brain goes, “Who’s that?” But before you can consciously consider that you’re wondering who that is, a man you already know goes, “Ah, my darling wife!” Loop opened. Loop closed. You barely noticed it, but it still serves to advance the story in a way that pleases you and prompts you to stick and stay.

Here’s a look at various-sized open loops in Game of Thrones:

Truly engaging shows don’t rely on just one type of open loop. Instead, they combine macro and micro loops into one experience.

It’s not the size of the open loops that determine a show’s success but the blending of large and small moments of intrigue over time.

Game of Thrones was so unbelievably gripping because they were among the best shows ever at using open loops. Hidden though most of them were, the writing, acting, and directing all formed a complex network of open loops which held our attention over time. We didn’t think, “Wow, what great open loops!” We just felt the urge to keep watching. We didn’t want to watch this show. We needed to.

Now here’s my entry for the Most Obvious Statement of the Year Awards: You probably don’t make a show like Game of Thrones.

While it’s easy to see how a show like that — big budget, entirely scripted and acted, and heavily produced — could incorporate open loops proactively and strategically, it might be difficult to see how you can incorporate open loops into your show too. That’s our challenge. That’s our opportunity.

I think any show, with any amount of resources, no matter the format of the episodes or premise of the show, can and should use open loops. For our shows to hold attention, the open loops we use can be scripted ahead of time or spoken in the moment. They just have to be.

Let’s set aside high fantasy and big budgets and learn about the five types of open loops you can use — regardless of your show’s genre or scope.

The 6 Types of Open Loops

Let’s start big and get smaller, looking at the macro open loops that sit across big swaths of story, then zooming in until we arrive an open loop so small, it’s just one word long. (It might just be the best place to start on your show, too.)

To recap, remember: Shows are about earning trust and love over time. To do that, we need to create an experience worthy of their time investment. In other words, we aren’t in the business of grabbing attention but holding it. As I’ve said a million times before: This work isn’t about who arrives. It’s about who stays.

Thus, the open loop is how we honor our Golden Rule: get them to the end.

Okay, now we’re ready to explore the specific types of open loops, going biggest to smallest. As a reminder, these all work together, with one show containing many or all of these six types of open loops.

1. Show Loops

This is the most macro-level loop. With a show loop, the entire project is positioned as one continuous journey to understand something — marketing, podcasting, the use of baseball as a source of stories and analogies in 20th century American literature, or whatever it is you explore and aim to understand better over time.

In a way, the show itself is the loop (meta, I know, and yes my brain hurts too). It’s as if you’re asking a big question and then your answer unfolds not as one statement but as a series of episodes, all of which forms that one coherent answer. Here’s an easy way to think about show loops. It’s like saying to your audience, “THIS is what we want to know. I don’t have the answers, but we’re going on a journey to figure it out.” The journey is the show. The entire project is itself one big loop.

The only way to close it is to end the show, though we can provide supporting moments of closure using smaller types of open loops further down this list. We can also publish what I call “apex projects,” which serve as totems or culminations (a form of closure) reflecting on the progress we’ve made so far in the show. For instance, after 100 episodes, publish a book.

Back to our quick examples above: shows about marketing, about podcasting, or about the use of baseball in 20th century American literature. If you’re asking one really broad question for each of those shows, thus creating an open loop sitting across the entire project, it might be these:

After a decade of disruption, what does it take to master marketing today?

As showrunners, what does it take to make someone’s favorite podcast?

How did baseball shape not just athletics but the broader society and culture of the 20th century, and how does that affect today’s world too?

You don’t need to make Game of Thrones to go on a grand quest, but you do need to ask questions that can’t be answered with a quick Google search or chat with an expert. You could explore something serious or something fun. You just have to work to understand, improve, or change something over time, across the entire show. That’s a journey. That’s a show loop. It’s stated by your premise, and it unfolds across every episode.

Examples of show loops:

- StartUp: Will this new company succeed?

- Breaking Brand (from Buffer): Can this agency pivot from serving DTC brands to creating one of their own?* (Buffer’s new show)

- Andrew Davis’s video show, The Loyalty Loop: What would marketing look like if we focused more on loyalty and less on acquisition? (And yes, I had to list this because, well, #LoopLoversUnite)

Only some shows will use a show loop, because only some shows overtly state that they’re exploring one or more big questions on an ongoing basis.

2. Series Loops

Whereas a “show” is the entire collection of episodes, a “series” is a single run of episodes, often positioned as different or special compared to the rest. The classic example is the “miniseries” — taking a few episodes to explore one specific idea more deeply compared to your “usual” episodes. But a season is also a type of series. So is a two-part special edition, or a recurring type of episode published once a month. Unlike the show loop, the series loop doesn’t encompass 100% of the content, just all the content inside the series.

One easy but effective way to introduce a new series is to overtly tell listeners that you are doing it. “Hey, this will be a unique and original series, separate from the rest. Here’s what we’re going to do, and why, and for how long.” This type of overt introduction helps further create an intriguing open loop, while also giving you permission to play around a bit. It’s a sort of implied admission to your audience to not worry if they dislike the series, since those episodes aren’t the usual types of episodes you do.

Sometimes, you’ll never do those types of episodes again. Sometimes, you’ll learn something important you can use back in your typical episode format. Other times, you might decide to create a series every X episodes or Y months to liven up the show and more deeply serve the audience.

Series can help keep the show fresh, including the largest possible series, a season. The reason why isn’t just that they are different but that they provide very distinct open loops. They’re not just different. They’re intriguing. For X episodes, you’re opening this one loop and plan to close it by the end. That’s the entire aim: provide closure by the end of the series. The point of a series loop is to declare up front to your audience: We want some closure on THIS specific thing. Join us on this series to find it, together.

Examples of series loops:

- Serial Season 1: How was that girl really killed?

- “The Other Latif” — a one-time miniseries with Radiolab, sharing the story of a Guantanamo Bay detainee who was technically free to leave but became caught between administrations and got stuck there. (He also shares a name with the producer of this series, who’d always believed nobody else had the same name as him in the world.)

- “Yes, Yes, No” — a recurring series of episodes on the podcast Reply All which aims to solve tricky and almost mysterious technical problems facing listeners.

It’s worth pointing out that series are wonderful vehicles to create co-marketing partnerships. Together with your partner show, you can jointly explore something you both care about and both share the responsibility for building community around that miniseries. That might mean all episodes run in both shows’ feeds, with the hosts directing their own audience to check out the other show, or it might mean that the series begins in one feed and ends in another.

(I’ve previously tossed out the idea of a story chain among multiple shows, where a series could span several podcasts, not just one or even just two. Haven’t found the right partners to try it just yet, but I stand by the idea.)

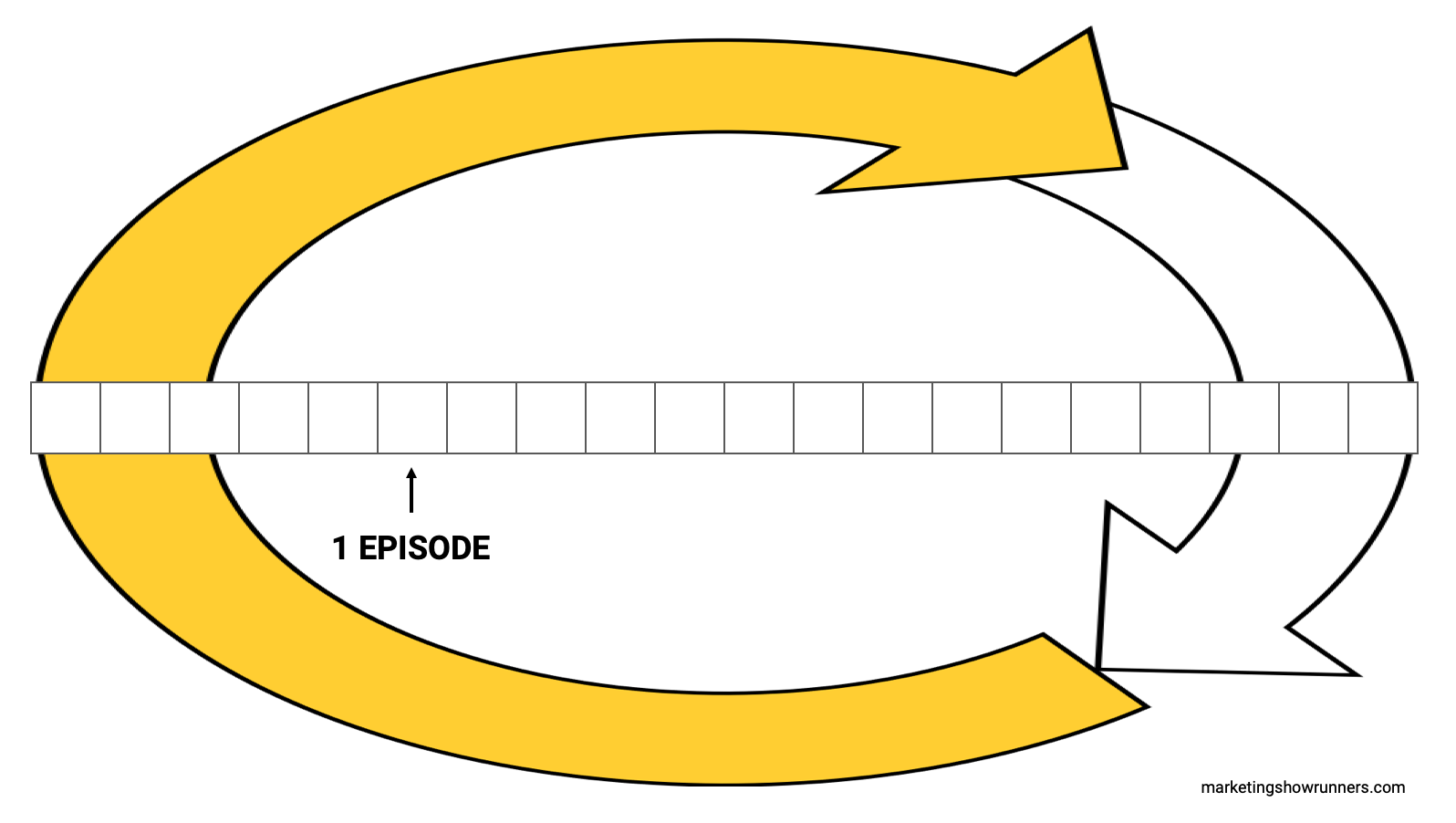

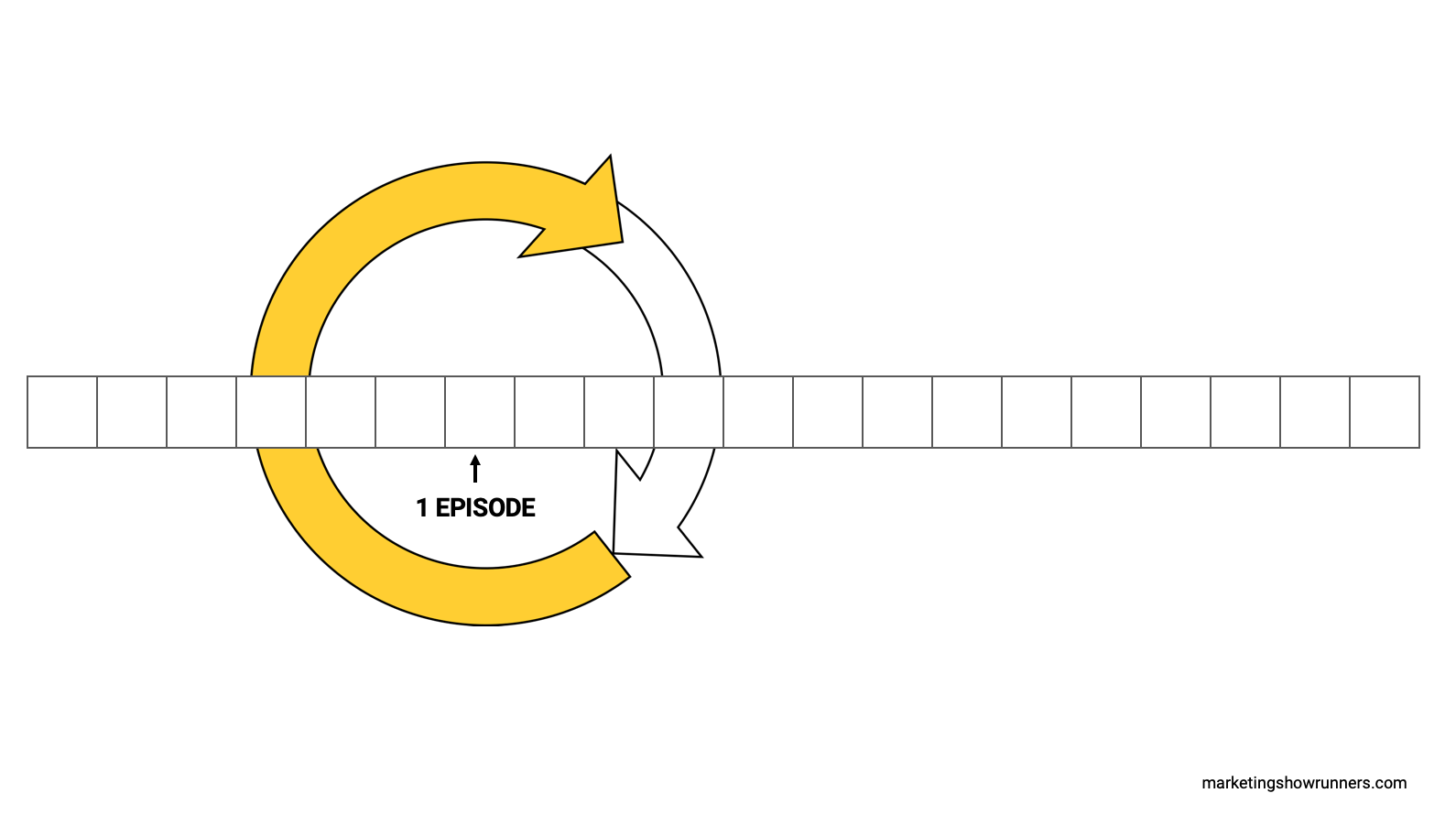

Show loops and series loops are the two macro-level open loops, in that they sit across episodes. It takes multiple episodes to provide closure. They rely on the micro-level open loops to deliver great content inside each episode. To see the next three types, we have to zoom into one episode.

3. Episode Loops

If you really want to distill a showrunner’s job on the production side to one singular aim, it’s to produce increasingly better and better episodes. Even the strongest initial episode done that exact way too many times in a row can grow stale. A show is nothing if not the process of constant reinvention. (There are 5 ways to reinvent a show, found here.)

Given this reality, each episode should offer something intriguing, rather than trying to rely on unspoken or assumed understanding of what the show is all about. Instead, tell people what it’s about and why they should care. This sometimes means re-stating the initial purpose of the show during the intro, but it almost always means creating an open loop across the entire episode. What’s intriguing about the episode today? State that out loud, or at least make it known through story or open-ended questions to the listener. Then, be sure you deliver the closure people require by the end of the episode. (Bonus points if you can find a way to open the next episode’s loop in the closing moments of your current episode.)

One easy way to execute this tactically: Use your intro to raise anticipation and create intrigue, i.e. open the loop.

Episode loops are the first type of micro open loop, but we can go further inside our episode content to look at something even smaller:

Example of episode loops:

- This episode of 3 Clips. What are the hidden elements of great interviews we often overlook, which Brian Koppelman uses so well?

- This episode of Good One. How did comedian Patton Oswald craft this particular bit?

- And, arguably, every episode of This American Life provides an episode loop. They focus on one theme, explored through different stories and vignettes.

4. Section Loops

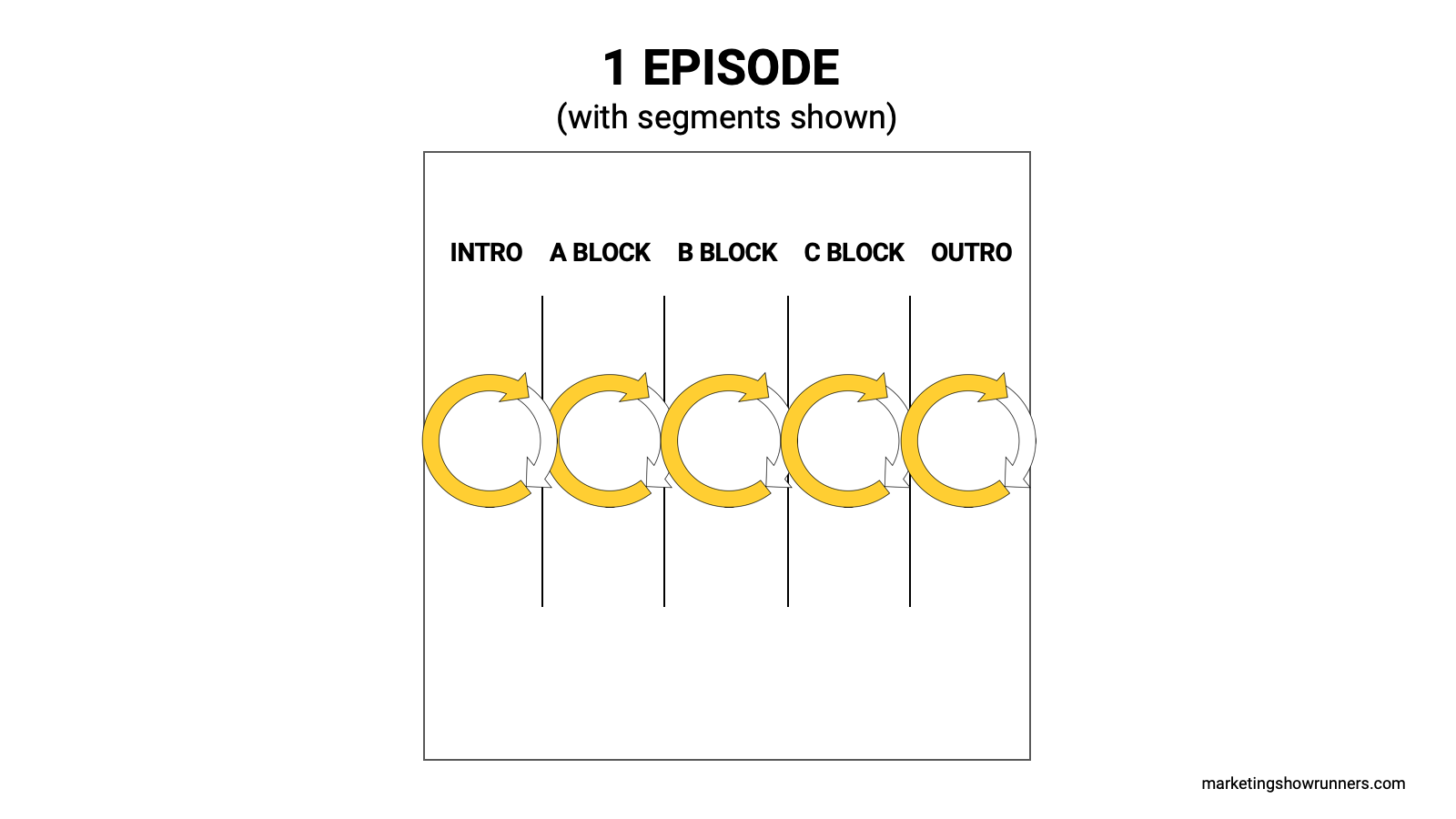

Inside a gripping show in any genre is a set format, a repeatable framework to guide the episode forward. That could be an interview with a few distinct areas the host wants to hit, in the right order, or it can be a complex narrative with component parts and pieces running end-to-end. This structured “rundown” (sometimes called the “run of show”) is used to create an identity for the show, as episodes feel like uniquely THAT show’s episodes. The rundown is also used to honor the Golden Rule and get people to the end.

The rundown is made up of blocks (sections which have a distinct purpose for the experience or story) and beats (moments within the sections). Not surprisingly, those are the next two types of loops: section loops and moment loops.

(By the way, if you want to learn how to craft your episode rundown, I’d suggest this article.)

In an episode rundown, each block should have a set purpose, serving the larger premise of the show. One example is the introduction section, which should be used to set the tone and raise anticipation for the episode to come. In other words, every episode open has the same goal: prompt them to eagerly listen to the rest. (Open loops used in the introduction of an episode are often called cold opens.)

This is often a wasted opportunity by many show hosts to raise anticipation and intrigue, because it devolves into housekeeping and droning introductions of ideas, hosts, or guests — i.e. oversharing of context. Instead of providing all the answers to listener’s questions, great introductions use open loops to create questions.

Let’s look at an example of this block-by-block use of open loops to illustrate what section loops do for a show — and how we can decide on where and when to use them.

My personal podcast, Unthinkable, is a show about creativity in business where we aim to prove that questioning best practices to follow your intuition leads to better work. Inside the episode structure, then, I need to break down that premise into a set formula. If that’s my concept, how does it manifest into an episode? I need to make a logical, lawyerly case, end to end.

So, whereas most shows may introduce a story by giving you context on the subject in the form of a brief bio, I introduce a story by first visiting the starting point in questioning best practices: Why is the best practice deemed to be “best”? How is it inescapable and smart? How hard would it be to question it?

The next block is then a quick reveal of how our subject broke from that seemingly inescapable best practice. By building up the best practice in A Block, and then breaking from it in B Block, their work seems unthinkable. Next, we hear their side of the story in C Block. How is their explanation logical? How were their actions radical? In a way, my show is really Not Unthinkable. So, how does the story of what happened reveal that breaking from a conventional approach led to better work?

Then, finally, in D Block, I visit the backstory and bio. How did they arrive to this moment? What’s their deal? How could they see this opportunity when so few others did?

We then end with E Block, where I narrate some insights and try to inspire.

Each block opens a loop, then closes it, advancing the action. These are section loops.

But inside one block, one section, are multiple moments, often called the “beats” of the episode or story. The beats make up the blocks. The moments create sections.

5. Moment Loops

These are really nuanced and a lot more hidden than the others so far. We’re getting very “micro” now. So let’s use some made-up content from a made-up show and try to revise it to better contain these moment loops.

Let’s say you host a show that debunks myths about technology.

Here are a few moments inside an episode that contain no moment loops, and thus, they fall flatter than they should, and don’t create much of a need to keep listening (both to these moments and to future moments yet to come.)

Note that all facts and stats are completely made up.

Most people think artificial intelligence is like a robot, shaped like a human, which speaks like a human, moves like a human, sounds like a human, and can solve complicated problems or create things like a human — or maybe better. The New York Times recently asked people which devices they picture when they hear the phrase “artificial intelligence,” selecting all that applied from a list. Sixty-five percent of people selected “robot with arms, legs, a torso, and a head.” Other popular answers included “drones,” “self-driving cars,” and “factory assembly line equipment,” as at least 35% of respondents added any one of those to their lists.

According to a leading AI expert from Harvard, Dr. Smarty McSmartpants, “Most people believe artificial intelligence is something very new, or even something similar to science fiction, like a radical thing the likes of which we’ve never seen. That’s because most people don’t know what TECHNOLOGY even is, let alone AI. They believe tech has to be a metal-and-plastic device that looks and feels overtly like machinery or electronics. They think technology advancements means they’ll suddenly experience the world in a very different way, like they’re transported to the world of The Jetsons or Star Wars. The truth is, technology is part of everything, and AI has been part of our daily lives for decades now.”

Again, I made that all up. Although if your name is Smarty McSmartpants, please contact me immediately. I need to tell your story.

Okay, so, the above paragraph is one approach to shaping a moment or moments. Essentially, all that stuff was about answering a question: What is the myth people believe is true? Above, we answered it. But we never really … asked the question. We didn’t open any loops, however quickly we’d shut them afterwards (as with any moment loop, we’d provide closure just moments later). It’s weird to contemplate, given that we’re supposed to be answering something in this hypothetical show about tech, but we didn’t create enough questions for listeners to truly, deeply care about these moments — nor feel a need to keep listening.

There was no loop. Just a flat line, marching forward.

Meh.

Let’s revise that same section to be stronger material for a podcast which aspires to be more than “meh.”

So how do we separate fact from fiction here? Well, we can start by understanding the fiction, and more importantly, how the fiction originated. Why do so many people believe in myths about AI?

Okay, so that’s our challenge together today. Let’s start here: What do most people think artificial intelligence actually is?

I’d ask you: What do you think it is? Any ideas? Here, I’ll give you a moment.

(Pause)

When you hear “artificial intelligence,” what do you imagine? A super-intelligent, human-shaped robot, walking, talking, doing crazy math problems, and recreating the Mona Lisa in mere seconds? What about crazy drones and self-driving cars? Chances are, when you hear the phrase “AI,” your mind serves up images rooted in science fiction. For better or worse, you’re far from alone.

According to a New York Times poll [stats from the poll].

One leading AI expert (and leading name-haver) is Dr. Smarty McSmartpants. He’s famous for his strong statements and opinions about how the public perceives technology, and here’s what he told us: “Most people believe artificial intelligence is something very new, or even something similar to science fiction, like a radical thing the likes of which we’ve never seen. That’s because most people don’t know what TECHNOLOGY even is, let alone AI. [Followed by remainder of his quote.]

Smartpants, indeed.

And all of that stuff makes sense. But one question remains: If AI has been around for so long, inside so many things we use or experience every day, then why is it only now becoming so widely discussed and hotly debated? Why do the images from The Jetsons and Star Wars suddenly feel a lot more … vivid?

NOW we’re making a podcast!

We opened a very intriguing section loop by planting questions in the listener’s mind. We used little moments to create open loops. This includes the use of…

- Open-ended questions (e.g. How do we separate fact from fiction here?)

- Addressing the listener directly and asking them to think about things (e.g. What do YOU picture?)

- Moments of silence to help the listener eagerly anticipate the next moment to come, i.e. the closure we’re about to deliver (e.g. anywhere we pause in that section above)

- “Signposts,” i.e. calling attention to specific details that are forthcoming to ensure listeners don’t miss it (e.g. when we said Dr. Smartpants is famous for strong opinions. What are those opinions? What does he sound like? I can’t wait to hear from him — oh, great, the quote is starting. I’m getting closure now.)

Thus, we closed multiple open loops, moment to moment. You might receive that experience as something seamless, but as we write or perform on the microphone, I know I must “purchase” tiny moments of your attention, little by little, to get you to the end. (It’s a fine line. For instance, ask too many hypothetical questions, and it starts to feel a bit bizarre. Done right, however, it’s an effective technique.)

When creating your episodes, look to create “moment loops.” These can be scripted and planned or happen organically as the way you speak or ask questions or tell stories. This constant opening and closing of micro loops, moment to moment, prompt listeners to stick and stay. They want to hear what happens next — or really, the need to hear it.

Finally, we arrive at the most micro open loop of all, the littlest one. Just look at him, sitting there all cute and mini. But just like anyone with an infant knows, the tiniest little creatures can change everything.

That’s the effect of this final type of open loop…

6. But

(Before I go any further, the answer is yes, I contemplated calling them But Loops, but all I could picture were Fruit Loops in the shape of a–well, let’s just say I’m ready to interact with other adults again and please let the pandemic end soon.)

But is the most undervalued word in hosting shows and creating content. But is this tiny little pivot point, this ability to create intrigue in an instant and create the need to hear what comes after the word. But is the promise of a new idea, a different direction, something we haven’t considered or heard yet. The payoff is coming, but … it hasn’t arrived yet.

(There, it just arrived. At least for that sentence. But we still don’t know the true power of the word.)

(Oops, I did it again.)

(Seriously, I need to go outside…)

In improv comedy, performers thrive on saying or thinking “yes and…” to whatever is given to them by a fellow performer.

But if you “yes and…” a cohost or guest or subject too much on a show, it starts to feel like pandering, removes the intrigue, and fails to deliver the most engaging content possible. You can “yes and” an episode to death. Used too often, and you’ll leave too much great material untapped, too many stories untold, too many topics explored solely from one angle — never turning it over and truly discussing or learning it.

Maybe you use but in your voiceover. “We all do this, but how often do we stop to wonder why?” It’s a tiny pivot between what people assume they know to what you want to explore.

Maybe you use but in conversation with guests or cohosts. “I get that part, but this is still confusing. It sounds like you did Phase One, but how did you get to Phase Two?” // “You keep saying to do X, but what about Y?” Polite disagreements, humble but still penetrating questions, and the willingness to explore a moment or idea fully from multiple angles — i.e., a rich episode — all depends on your willingness to use the word but.

(You can also use its cousins, however and yet. Maybe avoid its obnoxious neighbor, actually.)

Even the grandest of stories and most powerful of experiences can unfold because of that one tiny word. But is part of any great sequence of events. We think it’s “and,” but really … it’s but.

“This happened, but then that. Which led to this. But then that happened, which led to this.” Loop opening, loop closing, consistently over time.

Across your show and series, across each episode and inside our episode’s sections and moments, we are in the business of holding attention. If we want to get them to the end, we need to provide them reasons to stick around. Even right down to that one tiny but powerful word (oh hey, there it is right there), the choices we make determine the success of our shows.

Open loops are just tools. As with any tools, merely knowing they exist is a pretty useless bit of knowledge. Only when you start to use them to build something better does any of this help you.

Incorporate open loops both big and small into your show, and you’ll create something audiences adore. I believe you’ll get them to the end — no ifs, ands, or buts about it.

Actually, scratch that: Lots of buts.

Lots and lots of buts.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com