The Style Spectrum

NOTE #1: This is the second post in a three-part mega-series. If you missed Part 1, go back and read it here.

NOTE #2: This three-part mega-series is an important arc inside a larger, weekly journey that I’m on right now with thousands of other podcasters to understand one question: What does it take to create someone’s favorite show? Learn more and subscribe at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite.

![]()

Blink, and you’ll miss it.

That’s how fast a pike attacks its prey.

Pikes are predatory fish. They’re also not an animal you probably think about all that much. (Remember this blissful feeling. In about 10 minutes, that’s going to change forever.)

In the 1870s, a German zoologist named Dr. Karl Mobius allegedly created a now-infamous psychological experiment involving a pike and some minnows. This experiment can help us on our podcasting journey since, believe it or not, it explains why we so often fail in our mission to create someone’s favorite show.

We’ll revisit the pike and his propensity for prey in a moment. For now, a quick recap of where we left off in our mega-series after Part 1.

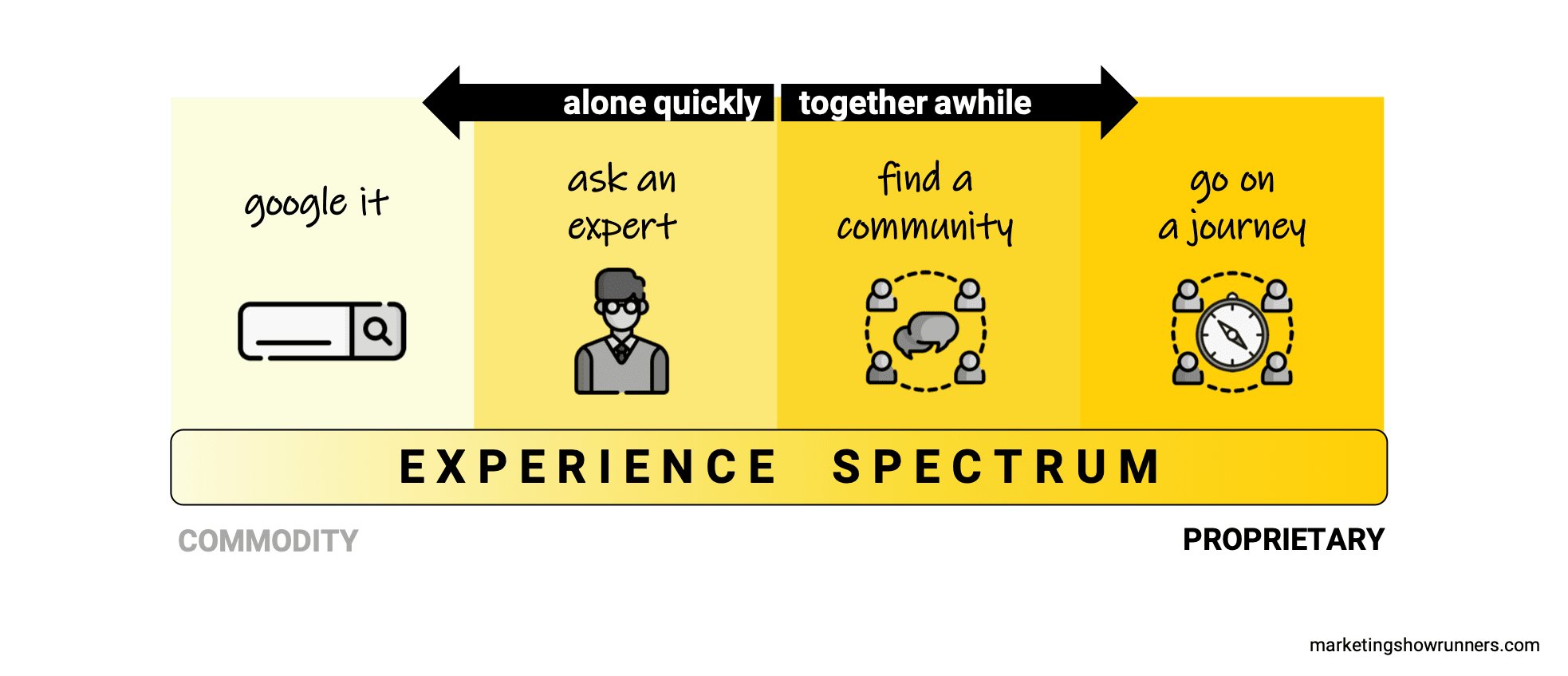

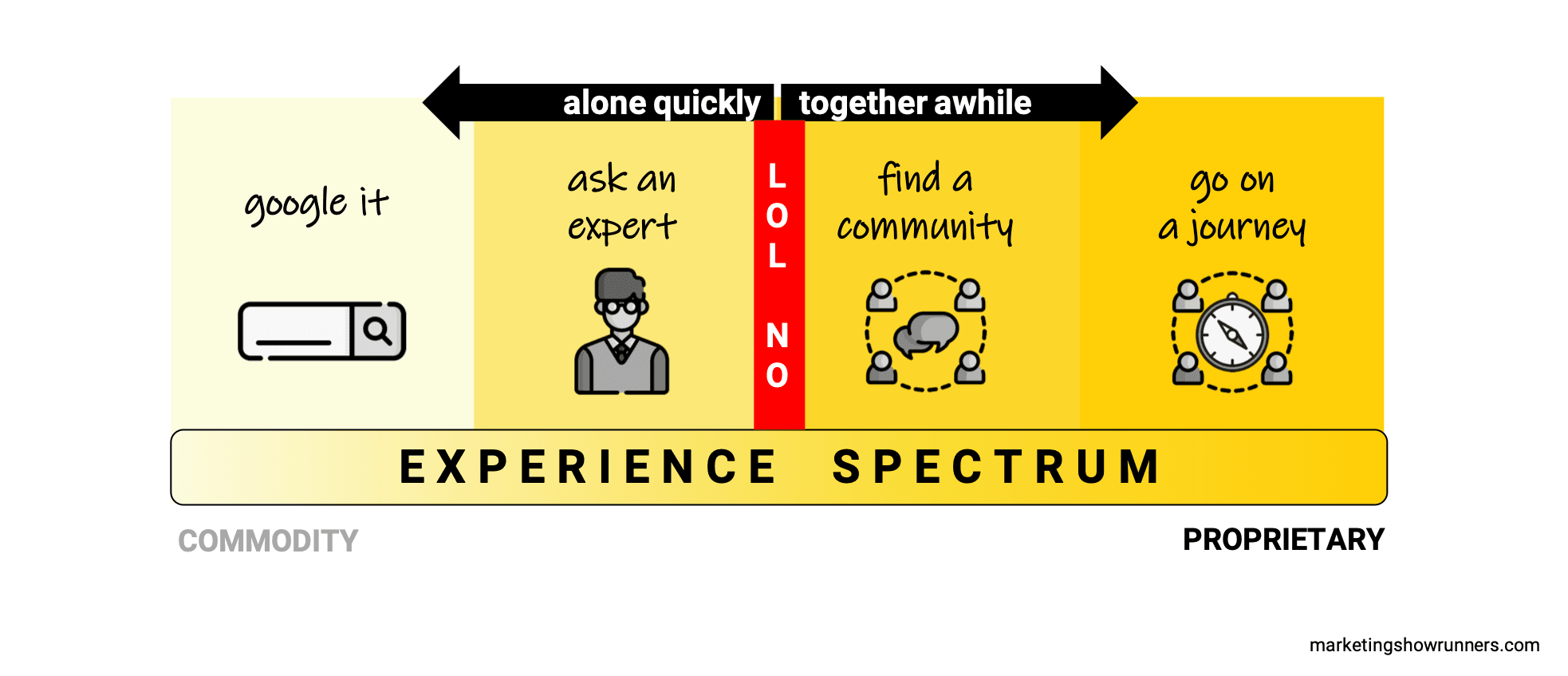

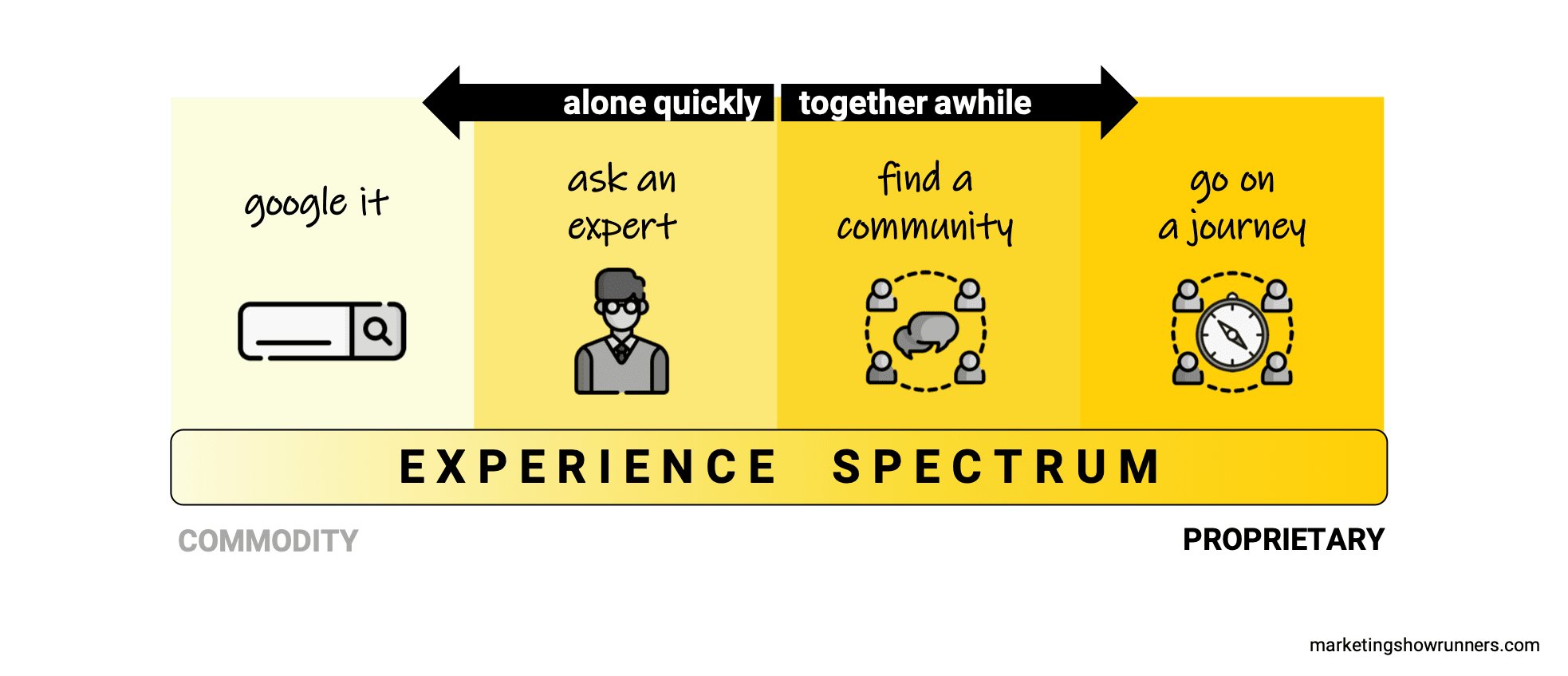

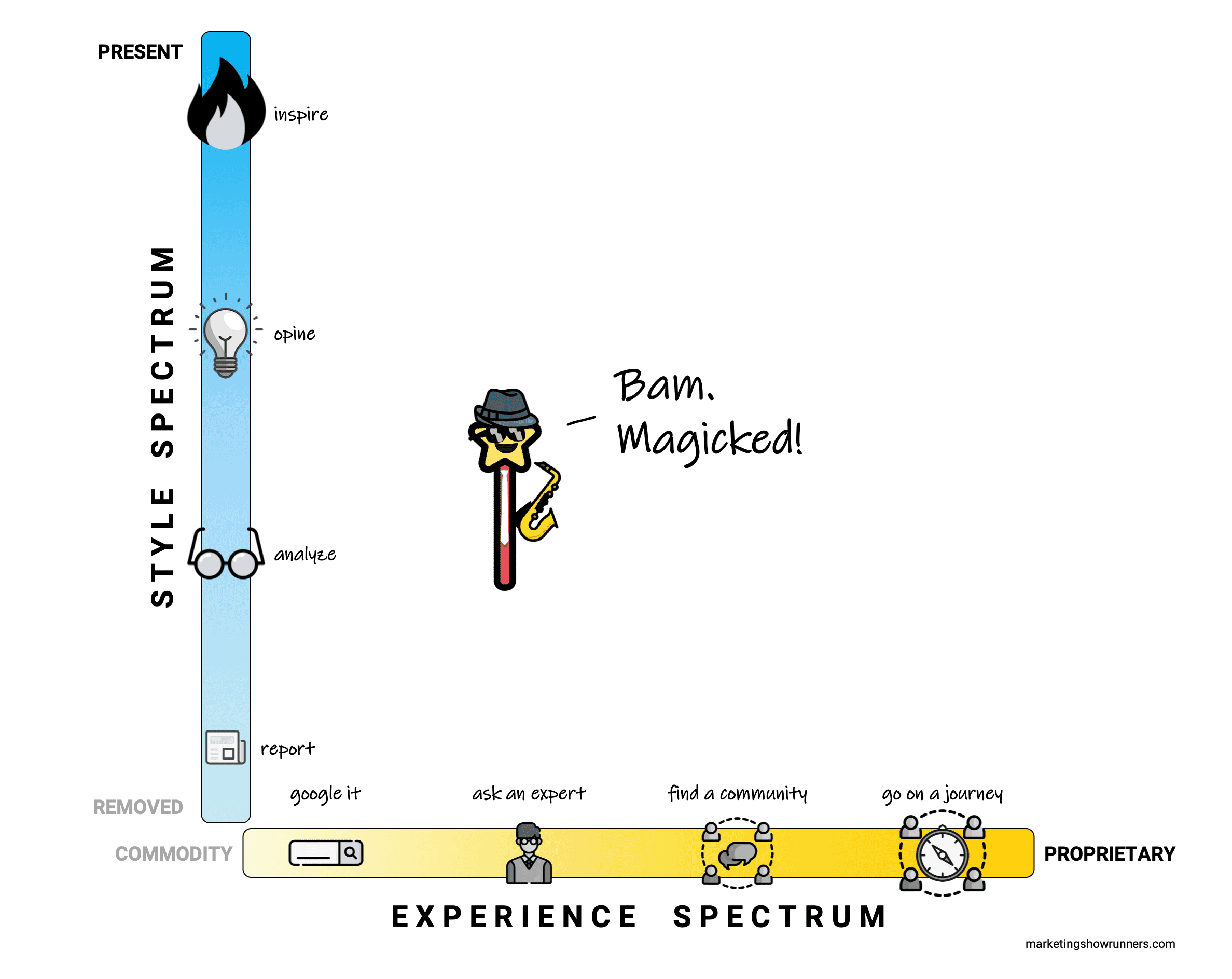

Last time, we created a new tool: the Experience Spectrum. The spectrum reveals all the ways others might experience our work, ranging from commodity experiences on the left to proprietary experiences on the right.

Our stated goal was to stop making transactional podcasts (things experienced alone, quickly, to merely acquire knowledge or a moment of entertainment) to instead craft transformational experiences (things experienced together, for awhile, because spending time with the ideas and people is the entire point — not finishing the transaction to be on your way).

If you haven’t yet, please go back and read Part 1 before going any further. The rest of this post may not make much sense if you don’t — especially our sarcastic-if-somewhat-helpful guide, Bob.

Bob is a 4,000-year-old magic wand who only grants two types of wishes. When I wave him with my right hand, he’ll show us a concept that helps us understand what we most desire to understand. When I wave him with my left hand, he’ll show us examples to help us understand that same thing.

He’s also very obsessed with telling everyone he plays tenor sax.

(He’s kind of a weird dude.)

(Like I said: weird dude.)

ANYWHO … in Part 1, Bob helped us (in his own roundabout way) understand the Experience Spectrum in order to answer the first question of three big questions we’re asking to re-think our approach to making podcasts:

1) How do others experience our show?

2) How do we personally influence that experience?

3) How do those two things combine to affect how others feel about the show? (How do #1 and #2 add up to someone saying, “That’s my favorite show”?)

After we re-think our approach, one mega-post per question, we’ll then shift the focus of our weekly email journey from how we think about our shows to how we execute, given all that we’ve learned.

Why we’re starting with how-to-think content, not how-to content: We don’t want to be great at following directions drawn on a map for us. We want to become great navigators. The ideal outcome of this journey is that we learn how to walk into any situation, find our true north, get our bearings, and proceed with confidence — leading others who are with us. Great navigators are practically unstoppable and unbounded in their ability to do that, but a map with directions is only as useful as that exact terrain and that exact route. Once the terrain changes or you encounter an obstacle blocking your path, you’re kinda SOL. It’s far more useful to be a navigator, so we’re starting there.

Speaking of obstacles blocking the path forward, at the end of Part 1, we encountered a pretty big barrier that stopped us in our tracks. We’d already built the full Experience Spectrum piece by piece, and we were in the process of moving a couple theoretical examples from left to right, when this happened:

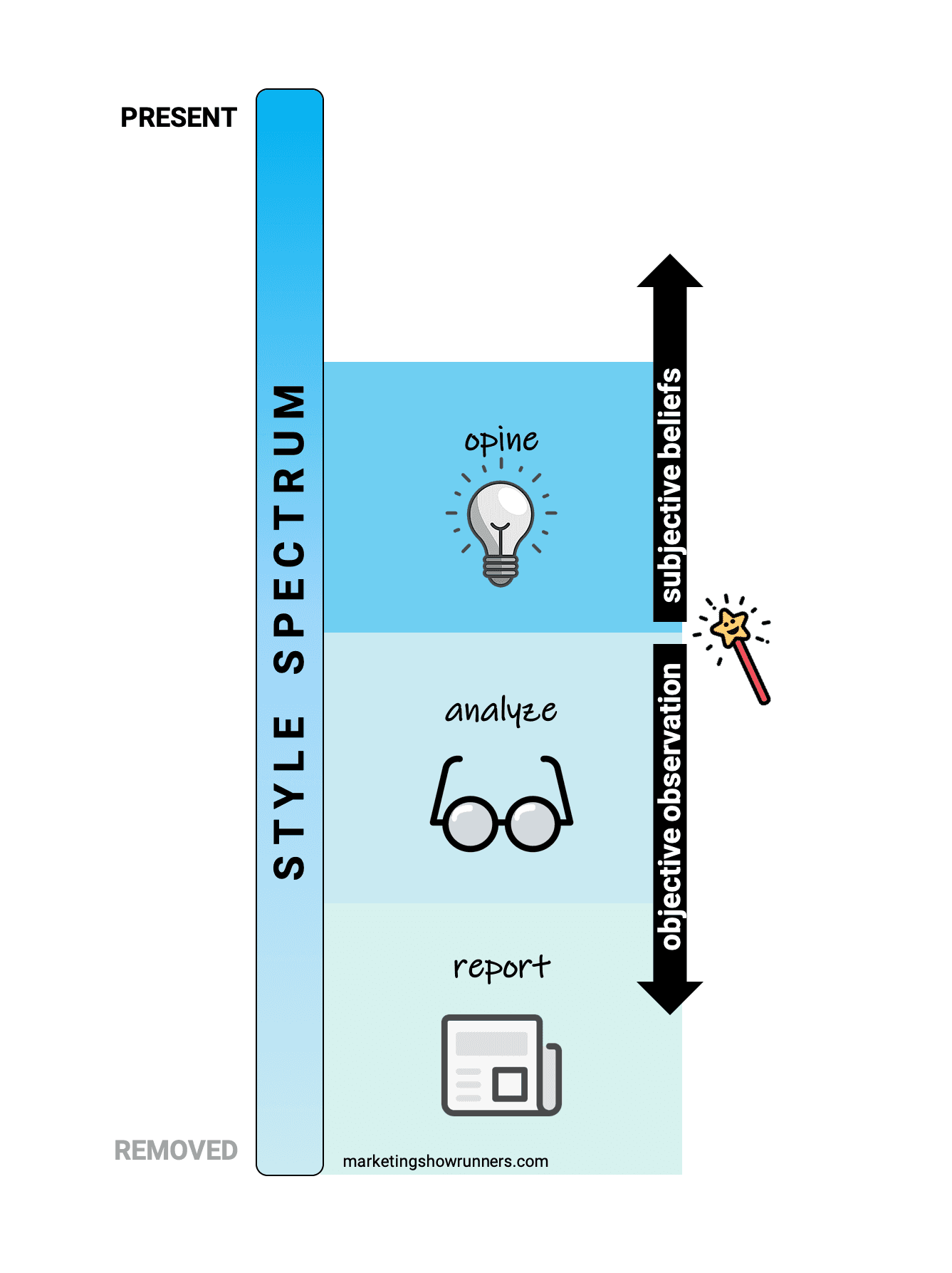

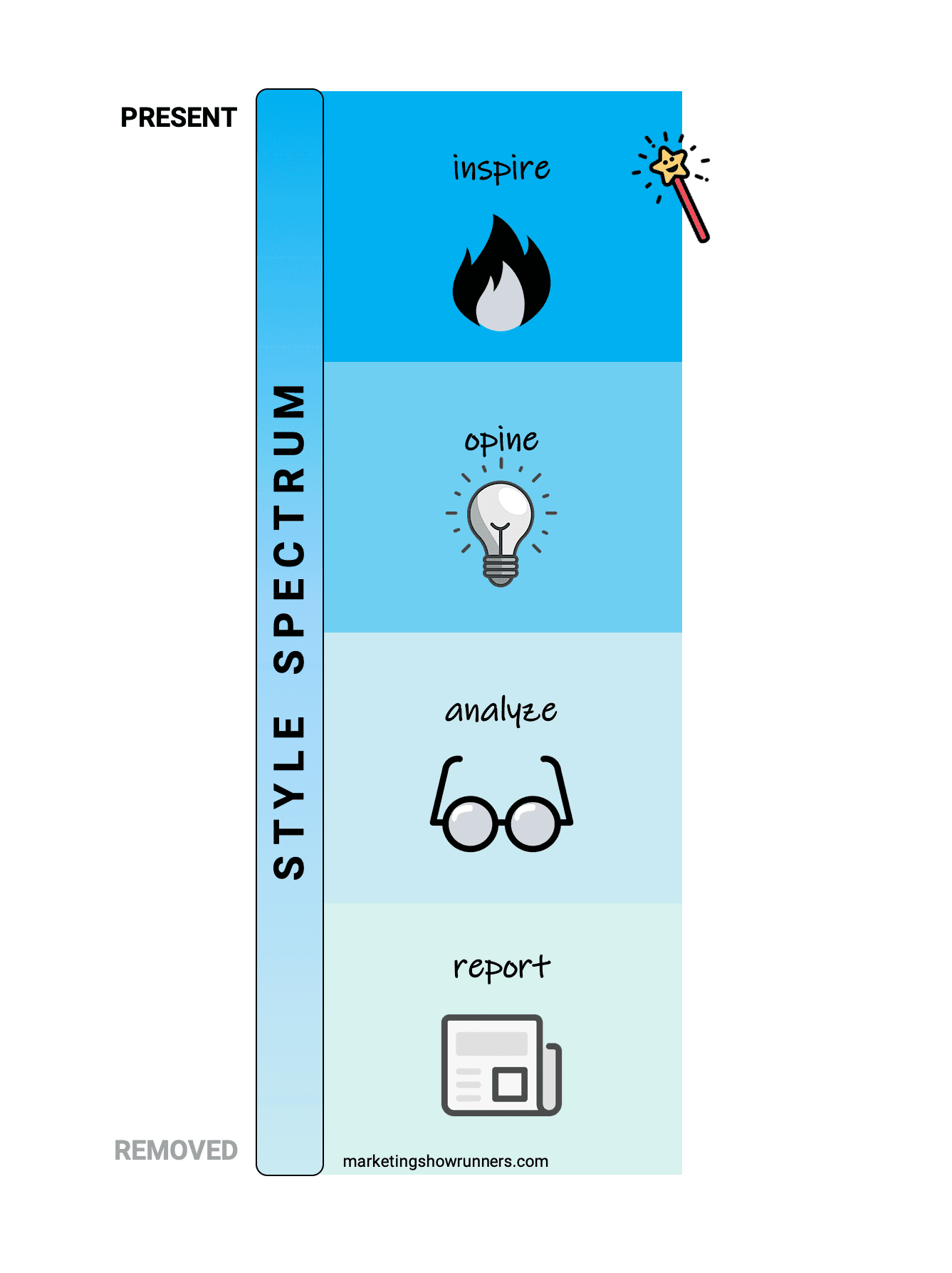

So what’s the deal? Well, to understand how to evolve our shows from a commodity experience (left side of the spectrum) to a proprietary experience (right side), we first need to understand something else: the Style Spectrum.

Bob, if you can be so kind as to revisit that?

That was the final thing we encountered last time: the Style Spectrum, which can show us all the ways we can proactively tip our shows from the left side of the Experience Spectrum to the right side. In other words, to succeed in making someone’s favorite show, you need to understand your own personal role in elevating the experience, from a commodity listeners could get from anyone, to something proprietary that only YOU could create.

As we established last time, the difference between a commodity and something proprietary is the story of what could be. Without it, a commodity is just a rather useless, raw asset. Gold is gold. Wheat is wheat. Iron is iron. Information is information — especially in the information age, no matter how “smart” or “enjoyable” it is. The source doesn’t matter much, as long as it’s “sound.” The best a given commodity can do is to affirm that it is indeed that commodity. That shiny, yellow, soft lump of metal professing to be gold? It is indeed gold. End of story. In fact, there is no story, and that’s the problem.

However, when the value is derived not from the “soundness” of the commodity but from the story of what could be, it transforms the experience. A shiny, yellow, soft lump of metal isn’t just gold. It’s also all the things that could be, as a result of you having some gold: wealth, or power, or beauty, or security, or nostalgia, or certain emotions, or literally anything, depending on the recipient of the gold. What story is being told by the seller, and what story is in the mind of the buyer? That’s the actual value, not the mere fact that this metal is gold. Commodities are rather useless without the story of what could be.

The problem with our podcasts is, too often, we just hand out the commodity. Here’s some information. You have it now. We have a podcast. You want that? Here. You have it now.

There’s no real story, and when that’s the case, we implicitly enter into a transaction with the audience. We offer an indefensible object, something they want to find quickly, suck into their brains quickly, and then move on just as quickly. The experience doesn’t matter: the quicker they acquire what’s inside the podcast, the better. The source doesn’t matter, either: they just so happen to get this from you, but they can get it from lots of places. It’s like we’re saying, You can find this from just about anyone, anywhere, and we happen to be an anyone, right here.

But what about a proprietary show? That is all about the experiencing of it and the source providing it. But to create that kind of show, we need to tell a better story of what could be.

Unfortunately, and somewhat ironically, to tell a better story to our audience, we first need to tell a better story to ourselves.

![]()

Section 1 of 2: The Story We Tell Ourselves

The rest of this post is divided into two sections: The Story We Tell Ourselves and Ascending the Style Spectrum.

Welcome to Section 1: The Story We Tell Ourselves. Here, we can revisit our friend the pike. In a way, it’s that speedy little bastard’s fault that the story we tell ourselves ends up limiting our work’s impact.

Let’s go back to that experiment involving the pike and some minnows. Here’s how it works…

Imagine the pike swimming around a tank. If you drop some minnows into the water, the pike will eat them right away.

However, if you lowered those minnows into the tank inside a glass jug, something different would happen: the pike, who can’t see the glass and doesn’t know what glass even is, will just keep smashing up against it in a failed pursuit of his prey.

However, if you lowered those minnows into the tank inside a glass jug, something different would happen: the pike, who can’t see the glass and doesn’t know what glass even is, will just keep smashing up against it in a failed pursuit of his prey.

As the experiment revealed, the pike might do this for hours. The result? He trains himself into thinking that minnows aren’t things he can eat. He then drifts to the bottom of the tank to sit there, feeling dejected. And can you blame him?

Finally, the minnows are released from the jug and can swim freely around the tank, undisturbed by the pike. Tasty little morsels are right in front of his nose, and he doesn’t move an inch.

This explains a psychological concept known as learned helplessness. It’s also referred to as pike syndrome.

Through repeated conditioning, personal setbacks, or when your initial intentions are consistently corrected, you no longer feel you have agency in a given situation. Sure, the minnows aren’t behind the glass anymore. They keep boop-ing the pike right on the nose. You’d think he’d go, “Oh, well, obviously, NOW is different than before. I can do something now.” But nope, he’s convinced that he can’t, and so he doesn’t.

A student who repeatedly gets things wrong on a few tests in a row starts to assume they’re bad at that subject. If the feeling persists, they might assume they’re bad at school or that they are inherently unintelligent. Regardless of the example, you end up accepting that there’s nothing you can think, say, or do in a certain situation, or overall. You’ve become helpless, and thus you need someone else’s help.

I think we all suffer from a degree of learned helplessness in our work. From the moment we’re taught in school that there’s a “right” and “wrong” answer, that’s how we approach every situation — including after we’ve entered the workforce. There must be a right and wrong answer for everything, and whatever we do, we just want to find the “right” one and avoid being wrong. As a result, rather than begin our process feeling empowered, we feel a bit helpless. We set aside our own sense of self-awareness or situational awareness, and we look for our answers out there — the expert, the convention, the BEST PRACTICE! (Cue angels singing.)

That’s the danger in seeking the absolute “right” answer: You end up settling for the average answer, the commodity approach. I’d argue that this trend has gotten worse than ever in the information age, as we all face the dark side of this era: advice overload. In a world flooding with everybody’s supposed “right answers” for us, what could we possibly do? What agency do we have? We better look for the right answer somewhere out there…

…but!

Tasty little morsels are floating right in front of your nose every day, if only you’d reach out and snatch them up. Insights, ideas, personality quirks, experiences, obviously relevant skills and memories, and seemingly irrelevant things too — infinite variables exist in your situation and nobody else’s, and all of them can be used to make better choices. Rather than look for the best practice in some general sense, you can get more specific and find the best approach for you.

Here’s the punchline: What’s the biggest variable of all?

You.

YOU don’t exist in any other situation. YOU are the expert’s worst nightmare. You’re the reason the One Simple Secret to Success can’t exist, or the Seven Simple Steps fall apart. You’re the reason the neatly packaged PDF or video course isn’t quite as helpful to everyone as it could be. You’re the outlier, the error message returned by the algorithm. YOU are the reason that no best practice is truly the best. Everything must first be contextualized and customized and consider the variables present in your situation, and of all those variables, you’re the messiest, most unique, and most frustratingly there for anyone who wants something to scale like a perfect machine.

As a result, the best a best practice can deliver is close enough, because it approximates your situation — nothing more. But you and I are not on this audacious journey to get “close enough.” We’re on this journey to stop making commodities and start crafting proprietary experiences. “Close enough” isn’t good enough when your one aim is to make someone’s favorite show.

This idea of learned helplessness — and the behavior change we can use to break from it — will be the driving force fueling the rest of this article, Part 2 in our mega-series. IF we’re going to tell a better story to our audiences, rather than just hand out commodities, and IF we’re going to stop offering transactional value to instead craft a transformational experience, then we would be wise to rely more heavily on the most proprietary thing we can offer our listeners: us.

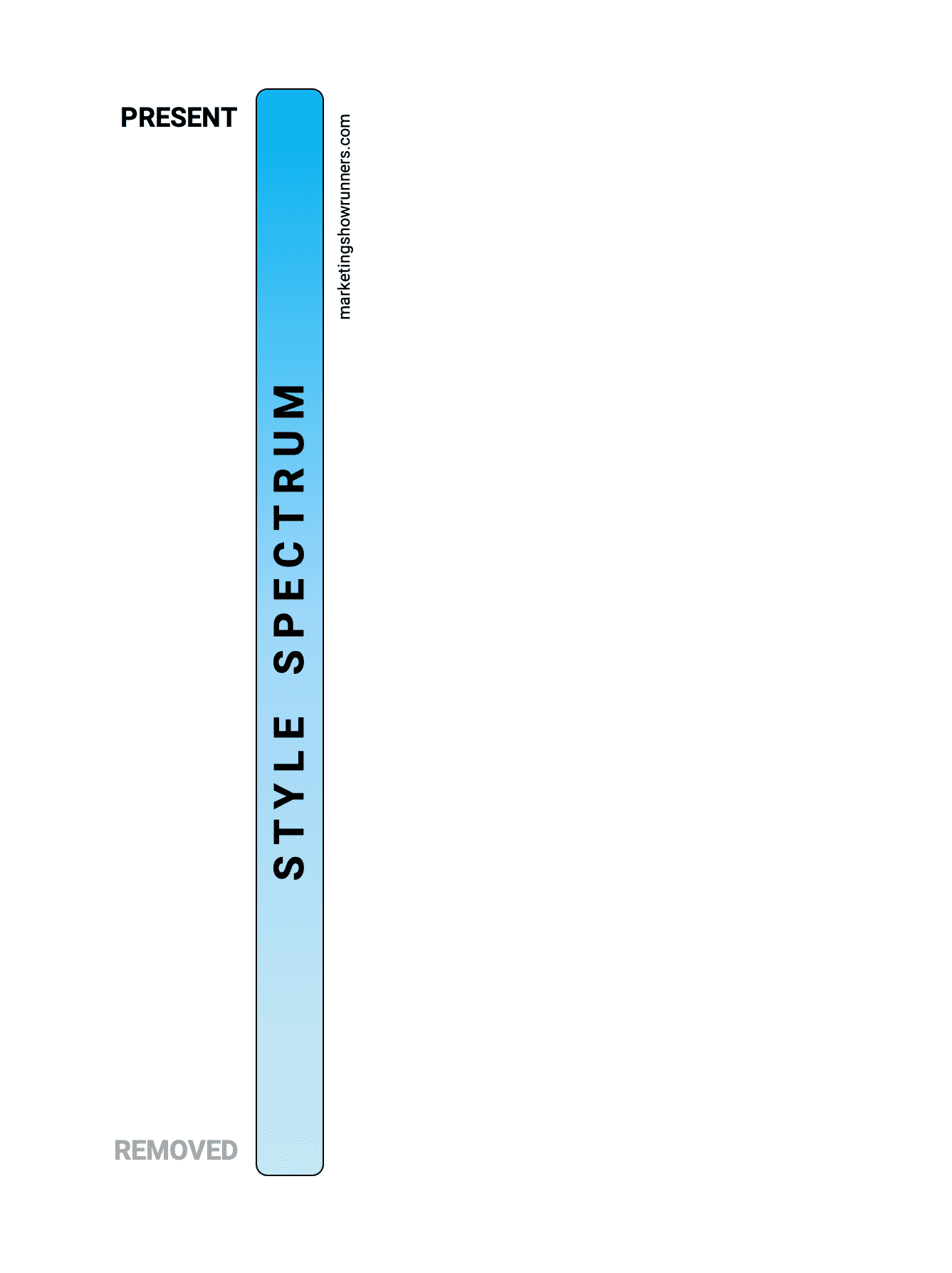

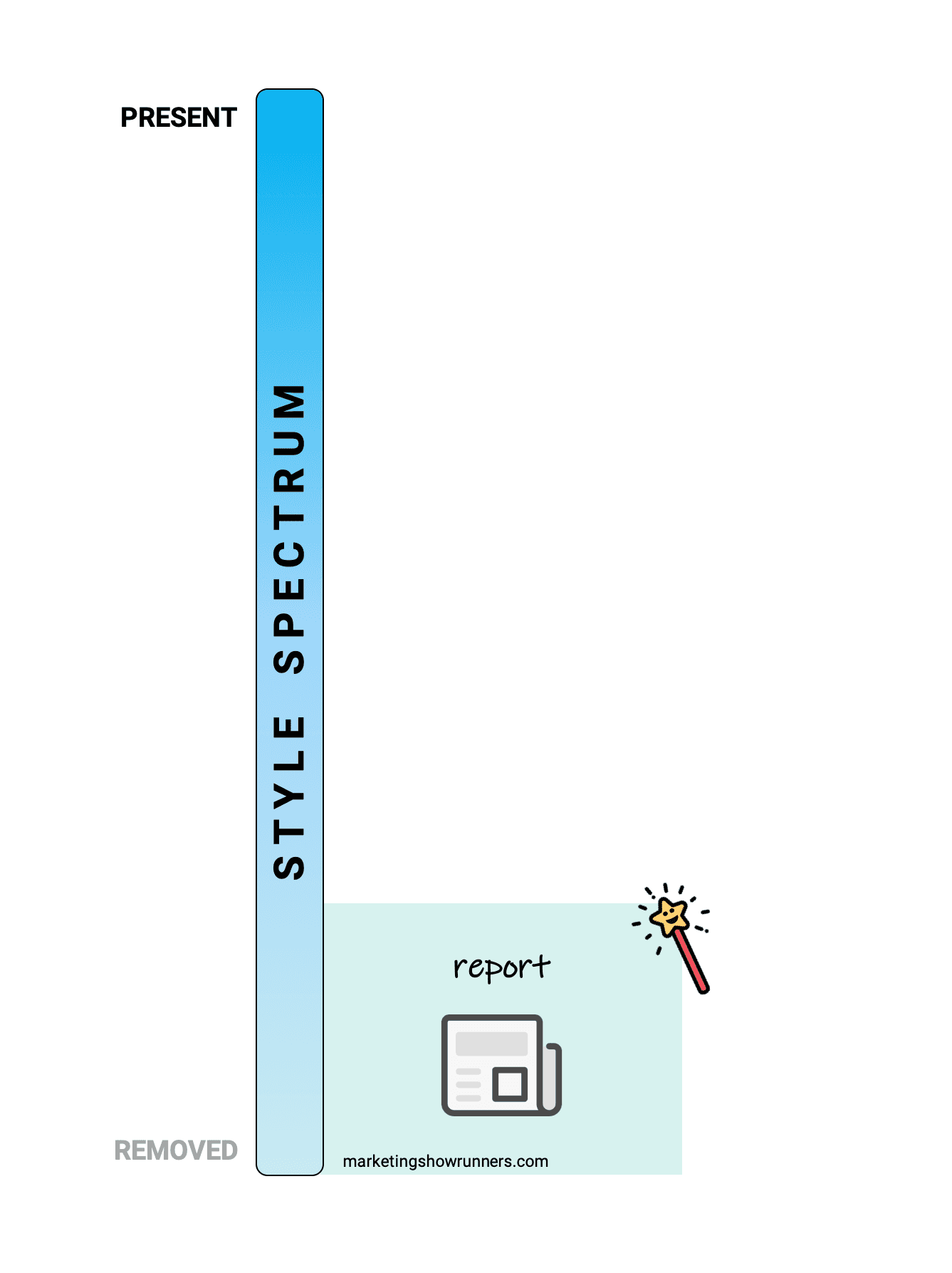

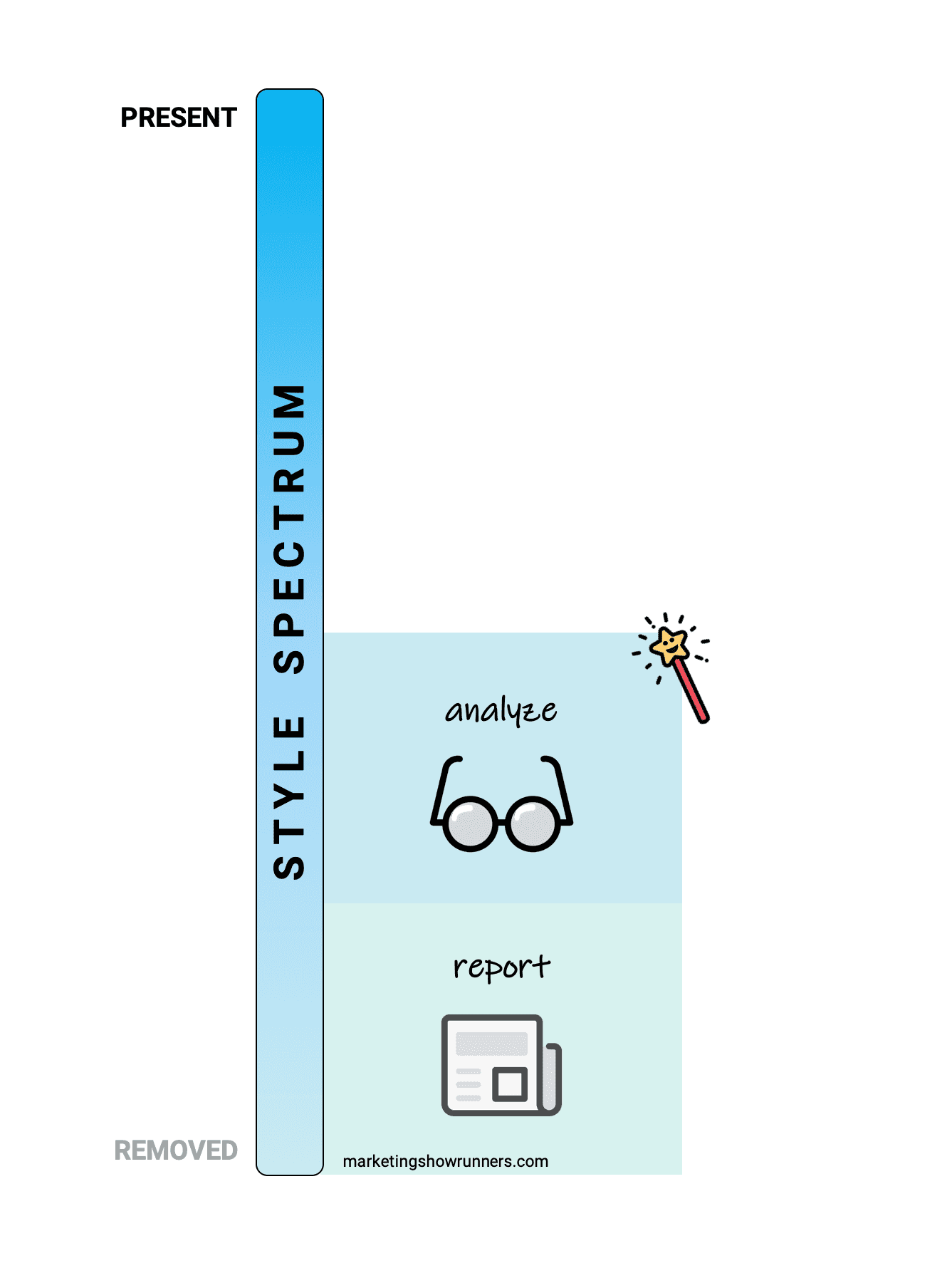

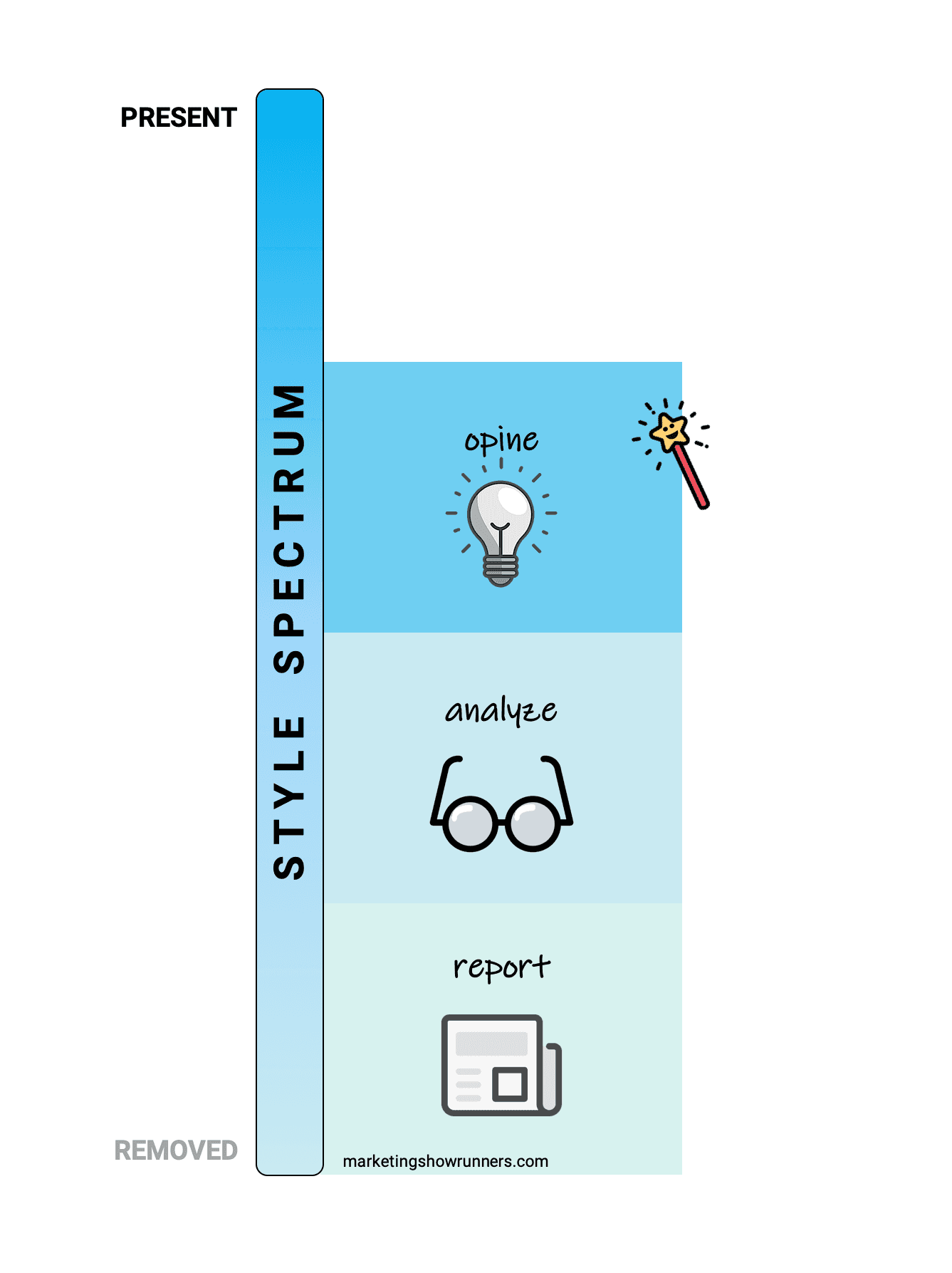

While the Experience Spectrum spans between commodity and proprietary experiences, the Style Spectrum reveals the two extremes of your own personal involvement in styling those experiences: you can be entirely removed … or fully present.

Let’s go ahead and update our lightbox:

Being “fully present” in your show isn’t just about the way you feel about the work. Loving what you do is wonderful, but it’s possible to love the process of creating something that audiences consider a commodity. No, being “fully present” is just as much about how you construct the show as it is how excited you are to do it. Your show should be strategically crafted to maximize the talents of you and/or your team. Simple enough to say. Surprisingly hard to do.

I’ve spent the last three years funding Marketing Showrunners as a media and education company in part through my public speaking fees. One of the big differences between a keynote speech which helps everyone at the event and a breakout talk off to the side is the very same idea we need to embrace about our role on our shows:

It’s a performance.

The version of you listeners get to know is not the same version of you they’d meet over coffee, which is not the same version of you they’d meet on a Zoom call, which is not the same version of you they’d meet at a party on the weekend, or on a stage at an event, or in a blog post, or a tweet. Everywhere we go, everything we do, we’re in some ways performing — learning to mold and shape and maximize who we are for the current medium and moment. THAT is what a performance is. It’s not about being some kind of overly dramatic actor. It’s about something more subtle, and arguably more difficult: Can you maximize your presence in this medium?

Here’s an analogy to explain.

In the Marvel comics and movies, Tony Stark is a charming, brilliant person. But send Tony Stark into battle, and he’d be crushed like a bug by a boot. That’s why Tony built himself the Iron Man suit, a vehicle that’s been strategically tailored to maximize his best attributes and add new abilities that would otherwise be impossible for him to possess.

Inside the Iron Man suit, Tony Stark isn’t a charming, brilliant person. He’s a friggin’ superhero.

I want you to approach your show like you’re building your very own Iron Man suit — a vehicle strategically tailored to maximize your best attributes and add new abilities you’d otherwise consider out of reach. A show has three core pieces, each requiring proactive planning and practice: the premise of the whole show, the format(s) of the episodes, and the talent. Once you step inside your carefully crafted show, audiences should receive the best-possible version of you that they can receive through audio. You’ve maximized that specific medium. You’re no longer just a charming, brilliant person.

You’re a friggin’ superhero.

(That’s right: MSR’s hidden mission this whole time was to create the Avengers of podcasters. The Podvengers … An elite team of supodheroes … Audio’s Mightiest Heroes … Led by Captain Podmerica.)

(I can do this all day.)

So, to move your show past the “LOL NO” barrier and across the entire Experience Spectrum, you need to go up the entire Style Spectrum. The only way you can go up the entire Style Spectrum is to rely wayyyyy more on a rather scary thing to rely wayyyyy more on: you. This is about your personal, unique involvement, your performance, and the careful crafting of a vehicle meant to maximize it and maximize you.

Our answer isn’t technology. It’s not a list of expert instructions. It won’t be a best practice. It won’t be more famous guests or trendier topics or some sneaky, hitherto unknown “growth hack” to land you thousands more listeners instantly.

It’s all on you, my friend.

It’s all on me, too.

It’s on all of us. Together.

The PODVENGERS!

(It’s right here that my brain went, Oh God, are we about to create a full-blown Podvengers graphic for this post???)

(Don’t worry, I came to my senses.)

…

…

…

…

(For a minute.)

(Yeaahhh turns out when I said Bob the magic wand was weird, I maybe was referring to someone else, too…)

(…he says, following a Podvengers bit, inside a blog post containing talking fish and a saxophone-playing magic wand.)

To Tell Ourselves a Better Story, We Can Unlearn Learned Helplessness

Look, I know saying “be a podcasting superhero” or “bring your full self to the work” makes for a decent Instagram post, but you and I have actual work to do on our actual shows, not to mention a million other things. We have to put the idea into action. So let’s revisit our pal the pike and find a practical way to advance up the Style Spectrum, step by step.

Last we saw the pike, he was in rough shape, what with a bunch of minnows taunting him and all.

Tough look for our guy. He truly thinks he can’t eat minnows. Tasty little morsels are conga-ing right past him, and he doesn’t bust a move.

That’s the core issue with pike syndrome: we stop paying attention to the details in front of us that could inform better decisions and more original work. We become mindless (as in, not mindful; not as in “dumb”). Our default form of decision-making in the information age is to thus rely on the conventional approach or the external ideas of someone else. We feel helpless. We need help. We can find it pretty easily. And we’re done. (What a lame move to bust.)

Marketing and psychology researcher Jim Mourey from DePaul University studies this idea of mindless decision-making and its ill-effects. Specifically, he examines a concept called cultural fluency.

The theory of cultural fluency is this: When the world unfolds as people expect (or have been conditioned to expect), they behave in predictable, routine ways involving little to no critical thinking. We just kind of … react. Said another way: when we feel too comfortable, or things feel too familiar, we don’t bring our full selves to our decisions. This is why the very bottom of the Style Spectrum is “removed.” You’re on auto-pilot. It doesn’t make much of a difference that it’s you in this situation, doing this kind of work or making this kind of decision. It may as well be anyone. You don’t matter. You’re on auto-pilot, doing what’s expected, what the average person would do in this situation.

When we fall into this pattern over time, the tried-and-true becomes tired-and-terrible without us noticing. When we finally do notice, our only options are to panic-fix things, frantically search for expert advice, or outright kill the project. Fortunately, Jim’s research suggests a very simple fix to mindless decision-making, i.e. a solution for those times when we’re too removed from the work and need to become more fully present.

I first interviewed Jim for my podcast and book, when he said this: “Culture guides our behavior on a very subconscious level, so when things feel culturally fluent, we go with the flow, and when they feel culturally disfluent, we stop, hesitate, and think a little bit harder.” Jim’s hypothesis is that we can introduce just a little bit of disfluency, a little dose of discomfort or something unexpected or unusual, and that’s enough to re-insert ourselves into a situation more fully.

To illustrate what he meant, Jim recounted an experiment he ran on some unsuspecting family and friends at a picnic. It was Fourth of July, when it’s culturally fluent to gorge yourself on food in America. (Guilty.) In the experiment, Jim handed half his guests festive plates with American flags and fireworks on them, and to the other half, he handed white plates. After they all went through the buffet line, Jim weighed their food. The folks with festive plates took more food than the folks with white plates.

Later that year, Jim tweaked the experiment and ran it again, this time at a Labor Day picnic with friends and family. (Seriously, if he invites you to a picnic, just say no.) This time, he gave half his guests plain white plates, while the other half received Halloween plates. (Again, it was Labor Day.) At the end of the buffet line, Jim found that folks who had the awkwardly out-of-place ghosts and pumpkins on their plates took less food than those with plain white plates. Taken together, this suggests that even small disruptions to the status quo can lead to better decisions.

“When there’s a cultural fit, when things are as they should be, people don’t really think. They tend to go with the flow. But when there’s a disconnect, suddenly things are strange. They’re not so strange that, consciously, we think, ‘Oh, I should take less food.’ It’s just that, for automatic behaviors, we do them less. We hesitate a bit.”

We hesitate a bit—that line really stood out to me. When our minds urge us to rely on familiar tropes and techniques, what if we hesitated just a bit? It only takes a tiny moment of pause in our work to plan something better than our usual approach, but the results can be far greater: a proprietary show, instead of yet another commodity podcast.

So how do we ensure we avoid cultural fluency on-demand, before we’re forced to panic-fix something or kill it entirely? Imagine that you have a crowbar that can be used to pry yourself free from conventional wisdom. I’d call that crowbar “open-ended questions.” The simplest and most commonly discussed open-ended question is “Why?” — and yet we still focus more on the “what” and “how” of our work than the “why.” I’d ask you: WHY? Because we aren’t aware of just how painful it feels when we don’t. It feels less urgent to think strategically than to act tactically.

But now that pike syndrome and cultural fluency have been revealed to you, I hope you can see: Open-ended questions prompt us to bring our full selves to the work. Rather than rely on accepted answers, we’re forced to think through more strategic questions.

Here’s the mantra we can all use for the rest of our journey together, the journey to make someone’s favorite show:

Stop acting like experts.

Start acting like investigators.

Experts focus on absolutes. They understand what works on average or in general. But we don’t aspire to be average, and we don’t operate in a generality.

Investigators focus on evidence. They may understand the same absolutes as experts, and may even rely on them from time to time, but investigators are much more focused on their firsthand experiences to dictate how they operate. Rather than profess to “have” the answers, they ask great, open-ended questions. Those questions pry them loose from culturally fluent, mindless behavior, force them to think more critically, and allow them to become more fully present in the decisions they make and the work they do.

For us, the status quo simply won’t do. We aspire to something better. We want to make something proprietary which transforms others. We want to be their favorite show.

“There are people who subsist in the status quo,” Jim told me. “These are the people who see the numbers, they’re meeting the numbers, and life is good, so they don’t need to change anything. But if you want to be truly innovative, what my research suggests is that this is not the correct approach. If you truly want to innovate and change, you need to break up that flow. This can be something as crazy as redesigning the workspace so it creates an experience of disfluency, or it can be something as simple as traveling.”

Both of Jim’s examples force you to hesitate a minute, get your bearings, and find your way proactively and mindfully. (That’s why travel is so inspiring: You’re forced to be mindful in a new situation. It’s not about what you’re seeing but how you’re forced to see it. You’re forced to be fully present.) In making our shows, both to ourselves and to our listeners, we can ask open-ended questions that require us all to be more mindful about what we’re doing, how, and most importantly, why. All it takes is a tiny moment of discomfort to make better decisions and craft better experiences for others.

I’m reminded of a great quote from David Bowie:

Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.

(Here’s the full video. It’s just a minute long, but he says a great deal more than the quote above.)

Our learned helplessness is the direct result of decades of education and workplace training that command us: Stay within your depth. THIS is your depth. Here, we’ve predetermined it for you. Here are the right answers. Everything else is wrong. Either you have the answers or you follow the person who does.

This is bullshit that’s been dried, dipped in chocolate, and sold as delicious. But we’re not buying it. In our line of work, we’re told to have the answers, but you’ll have far greater impact if you’re willing to raise your hand and declare, “This seems important. I don’t have the answers, but I know how to figure it out.”

You have some questions. They’re open-ended. There isn’t any one “right” answer. But you’re here to investigate. Once you invite others along, it becomes a transformational journey — the far-right of the Experience Spectrum.

Stop acting like experts. Start acting like investigators.

Stop shipping commodity content. Start crafting proprietary experiences.

While the pike may not have the tools to unlearn his learned helplessness, you do. Your abilities and the work you create can help you build someone’s favorite podcast — a transformational experience found nowhere else. In other words:

You can be a friggin’ podcasting superhero.

![]()

Section 2 of 2: Ascending the Style Spectrum

We’ve just completed Section 1 of this mega-post: The Story We Tell Ourselves. It’s time for Section 2: Ascending the Style Spectrum.

Let’s bring Bob back into our lives so we can build each piece of the spectrum, bottom to top.

Like I was putting a hat on a hat?

Or maybe a hat on a talking wand?

Yes, yes you did.

So, the Style Spectrum?

As a reminder, on the very bottom of the Style Spectrum, your involvement is almost nonexistent. You are totally removed. Yes, you spent time on the show. You might even host the show. But if we white labeled the entire thing, removing the brand and your name, people would have no way to identify the show as uniquely your company’s or yours.

That’s the dangerous bottom-end of the Style Spectrum. Let’s start breaking it apart into various tiers, bottom to top.

Right-o, I can just wave Bob here, using my right hand since we want to understand a concept, aaaand flick!

The most removed you can possibly be from your content is to simply curate some facts and report them.

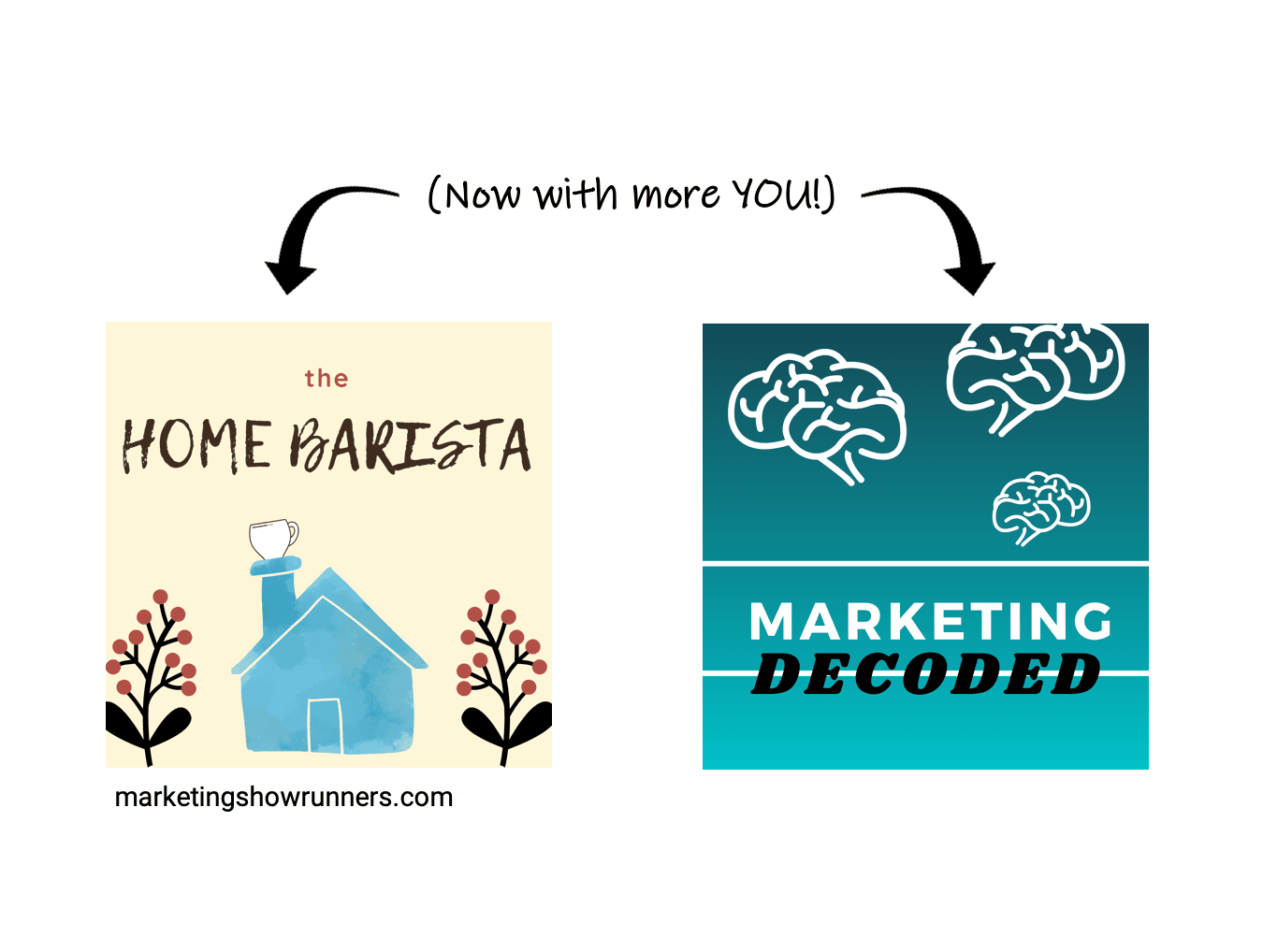

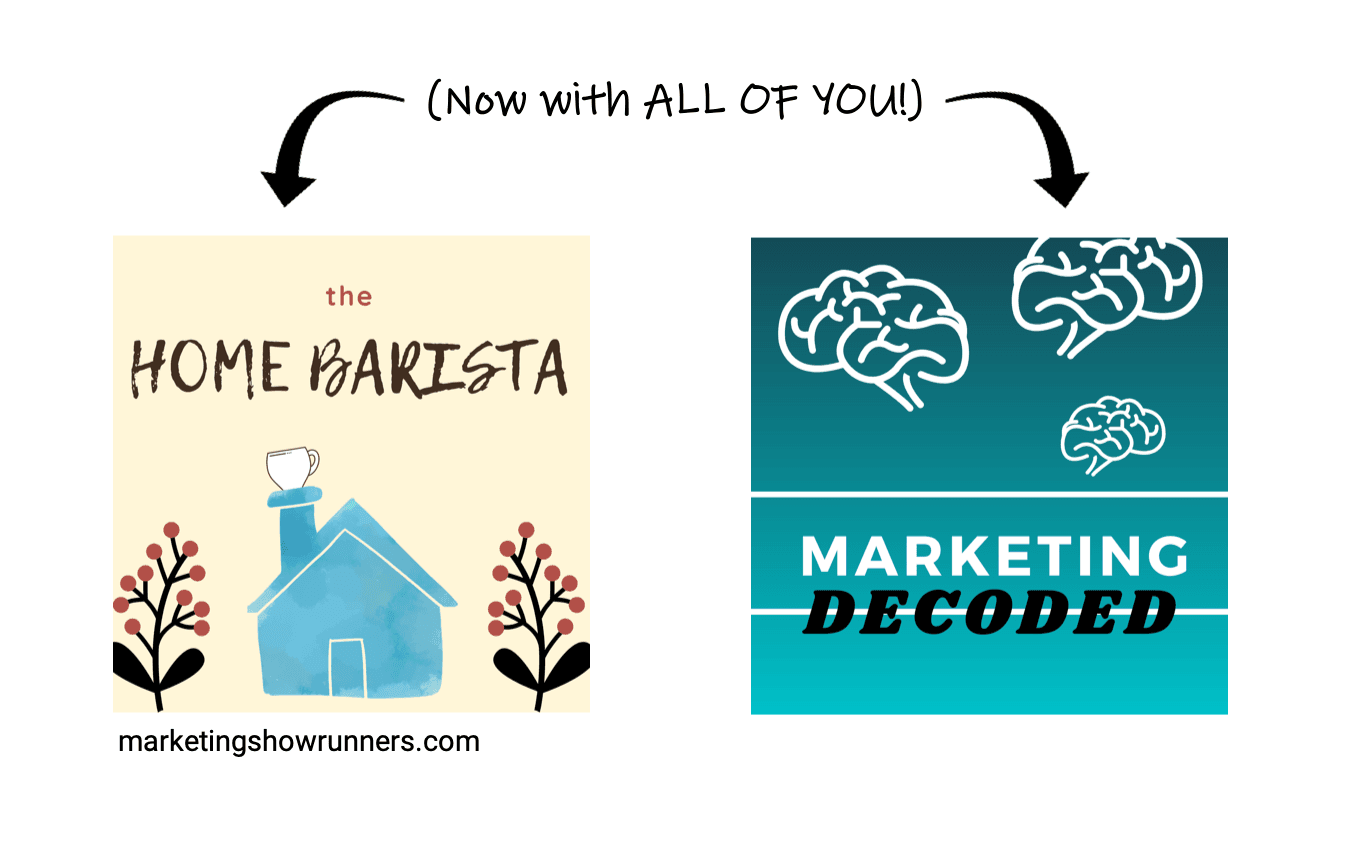

What does this look like? Let’s bring back two example podcasts from Part 1. I’ll just wave Bob with my left hand this time aaaaaand … they’re back.

The coffee brand’s podcast (The Coffee Lover’s Podcast) just hands out facts about coffee. Here are the popular trends. Here’s an article to read about coffee from this culinary magazine. Here’s something a major coffee brand did. Here’s a tool that might help you.

The marketing tech brand’s podcast (Marketing Trends) also just curates news and other stuff they found recently. What’s the latest in marketing this week? Who said or did or published what?

In either case, there’s very little involvement from the creator to the point that it almost doesn’t matter who they are. What matters is that the information, the raw asset, is sound. The commodity is indeed that particular commodity. (Is that wheat actually wheat? Yes? Good enough for me. Did the coffee brand really do that last week? Did that marketing blog actually publish the report you mentioned? Okay, cool. Thanks for giving me the raw information. We’re done here.)

Tough for you to earn more time and, as a result, earn trust and love. Tough to be anyone’s favorite show.

Crucially, the two example shows above do NOT include any hints at what the hosts or brands creating the shows actually think or believe about the stuff they’re sharing. It’s just the facts, soundly reported, plainly stated. That’s foundational for any content, sure, but it’s also woefully insufficient for our goal. (There’s a reason there aren’t many widely known or famous “beat” reporters in sports or politics. If all the writer does is talk about what happened at the game or inside town hall yesterday, the audience doesn’t develop much of a relationship. The writer doesn’t have much of a voice. They’re just good at gathering up some facts that you weren’t there to learn yourself. Important? Yes. Enough for our purposes? No. Not unless those beat writers begin to do something higher up on the Style Spectrum. But we’ll get there in a second.)

🏠 Properly reporting the facts is a foundational element of our content in the way a house’s actual foundation is important: without it, the rest doesn’t hold up. But the foundation itself isn’t the house. There’s a lot more that we need to do on top of the foundation to complete our jobs as builders.

On our shows, if all we do is curate the facts, we’d be better off publishing a blog post than a podcast, really. Or how about a blurb of key takeaways? Or a bulleted list? Or best of all, we should learn how to make one of those futuristic chairs from The Matrix movies that the audience can use to just download the information we’re offering straight to their brains in an instant. That’s what they want. They’re after the commodity, the information, not the experience of consuming it. We, the source, don’t matter all that much.

Uh oh.

In Part 1, about the Experience Spectrum, we used a recurring statement to understand what we are implicitly saying to our audience when we give them our shows. When we give them a pure commodity, we’re basically saying this:

🎁 Here’s some gold. You have some now.

Let’s update this line now that we’re incorporating the Style Spectrum so that the statement reflects our personal involvement in the experiences we create.

When we’re totally removed from the show, it’s like saying this:

🎁 I’ve collected some gold. You have some now.

[Awkward pause.]

Welp, see ya!

You gathered a bunch of stuff, and that’s … nice. But it ends there. Your involvement could be so much greater. So let’s head further up the Style Spectrum.

One step up the Style Spectrum: analyze the facts.

This is the realm of experts and, of course, analysts. When you analyze something, you aren’t just providing the facts. You’re providing context.

On this type of show, you’re doing more than just collecting some information and presenting it without further comment. (Welp, see ya!) You’ve curated soundly reported facts, yes, but then you point out how those facts connect to other facts. This is where expertise starts to matter. This is where you start to matter.

Thanks to the elevated level of involvement from you, the audience learns how one fact relates to another, or one trend builds on what came before it, and so on. By drawing connections between soundly reported facts, you aren’t just informing the audience. You’re teaching them. You help them do something far more useful than just know some stuff. You help them understand it.

If reporting a bunch of facts answers the questions of who, what, where, when, and how it all unfolded, then your analysis takes it one step further by answering a more complicated, more pressing question the audience will be asking: What does it all mean for me?

This is where a relationship can truly start to blossom.

What do our example shows look like at this stage of the Style Spectrum?

The coffee brand’s show evolved from the generic Coffee Lover’s Podcast into a more specific show, The Home Barista, a podcast offering expert analysis which helps coffee lovers make sense of all the trends, ideas, technologies, and news in the coffee industry, thus helping them become better baristas at home.

The marketing tech company’s podcast also evolves a bit, from Marketing Trends to Marketing Decoded. This show also promises to interpret and analyze the facts to help marketers make sense of their industry. Listeners aren’t just informed. They’re educated. They know what the information actually means. A report like “Mailchimp launched a thing for marketers this week” evolves into saying “Mailchimp launched a thing for marketers this week. This might seem out-of-scope for them, but their stated mission is [XYZ], and so it’s right in-line with what they claim to do for their customers. Also, we’ve seen two large competitors launch something similar so far this year. This is evocative of a major marketing trend we saw in the early 2010s…” (And so on.)

So why isn’t an expert-driven, analysis-based show higher on the Style Spectrum? Because you have so much more to give than just analysis. You can be far more present, in a really great way.

It’s also because, if we’re being honest, expert analysis is highly commodified today. Experts are everywhere. There are even experts who are experts on how to be an expert, and I’d link to a few, except they all emailed me six times since I started this sentence to ask if I’d link to their expertise or interview them on my podcast so they can share expert tips for experts who want to be better experts.

(Breathe, Jay. Breathe.)

Again, this is not to say expert analysis is unimportant. To the contrary, it’s crucial.

🏠 If the foundation of the metaphorical house is soundly reported information, then smart analysis is like sturdy scaffolding used to build something up. We’re starting to give shape to it all, but we still haven’t finished the house. The work of a builder is far from complete.

A quick clarification to make about expertise versus experts. The knowledge part of an expert (the expertise) is mostly commodified, but the people are not. The ability to interact with an expert is less commodified. While you can google expertise, the ability to actually converse with an expert offers a benefit that algorithms struggle to provide: the ability contextualize the information.

Unlike a quick google search, you can ask a follow-up question to an expert, which then allows the expert to further contextualize their knowledge to you. Additionally, the expert can choose to deliver the answer they think the person needs to hear, rather than asked to hear. (For instance, they might say, “I know you asked about the best marketing tactics to grow your podcast, but let’s start with things you can do to make the show itself better before you try to promote it to more people.”)

Google can’t do that.

Siri can’t do that.

Chatbots can’t do that.

(One more time for the people making these apps: Chatbots [billboard-sized Not Equal-To symbol] Actual Humans. Not now. Not ever.)

Thus, experts are somewhat proprietary to experience, even though expertise is pretty commodified. The difference is the ability to receive more contextualized information over time.

We’ve now moved from this:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now.

To this:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now. And here’s what people tend to do with gold.

We’ve started to climb the Style Spectrum.

But we can climb higher.

The next step up the Style Spectrum is to opine. You can offer your opinions.

Here, we move from this:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now. And here’s what people tend to do with gold.

To this:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now. And here’s what people should do with gold.

There’s one key phrase which begins to come up a whole heck of a lot more on your show at this stage of the Style Spectrum: “I think…”

That’s because the lower half of the Style Spectrum is purely about objective observation, while the upper half is about subjective beliefs. Let’s add two black arrows to our tool to illustrate the difference:

At the bottom, reporting facts requires you to remove your own subjective beliefs and purely observe, gather, and share. You’re a vessel, and the classic journalistic approach to reporting is to withhold biases, opinions, and beliefs.

One step up the spectrum, analysis, is still an objective approach to the information. You’re saying, “Here’s what people tend to do,” or, “Here’s what we’ve seen happen.” You’re connecting facts to facts, drawing lines between them, in purely objective fashion. Better analysis means better access to the truth of what has happened in the past.

When we start giving opinions, however, we prescribe what others should think, do, or say next as a result of the truth of what already happened. It’s like we grab our highlighters and start to emphasize certain lines of the analysis that we believe matter most, or else we scribble in the margins to share new ideas and beliefs and conclusions as a result of all the analysis. When we’re willing to opine, not just report or analyze, we begin to add something sorely missing from other, more commodified experiences: a point-of-view.

The experience becomes much more proprietary as a result, because the experience starts to rely way more on you.

In our quest to stop being so removed from the work and become fully present instead, we can proactively move up the Style Spectrum by adding a point-of-view.

The “Because People on Social Media Be Mad” Section

Because of what we’re enduring thanks in large part to social media (though I’d zoom out and rant about why it’s really ad-supported media to blame — but that’s a mega-post for another mega-day), I want to clarify: I am NOT saying uninformed, unwavering opinions are ever the goal. Ever, ever, ever, ever.

Blustering buffoons and pundits who pander to their audiences to stoke fear or even just to grab attention and amass influence are the exact opposite type of opinion I mean.

By “share your opinions,” I mean the well-reasoned, well-intentioned, helpful kind of opinion, like opening the door ajar for someone and saying, “Here, I’ve considered this, and have you tried going out this door? It might be wise, friend. Have a nice day!”

Let’s call these types of opinions worthy opinions. What makes them worthy is they’re built on the foundation of soundly reported facts and rely on the scaffolding of smart analysis. Without understanding the facts of who, what, where, when, and how it all unfolded, and without first considering the full context of how it all might connect in an objective way, it’s likely that the resulting subjective opinion will be a bad one.

My 17-month-old daughter has a lot of opinions. Some are good and some are bad, and the difference has everything to do with how many sound facts and how much smart analysis she can draw on to arrive at her opinion.

When she offers her opinion about, say, what’s happening in her diaper, I’d be smart to listen. She has the full context by now. She’s gathered the facts (hopefully cleanly inside her diaper). She’s connected the dots before (This sensation leads to this other sensation which leads to that new reality.) And so, she starts to opine: Wah.

A worthy opinion! I should listen.

You’re good, Bob, don’t worry. Washing hands is a thing every human does ridiculously often right now, parent or not. (You’re sure you can’t grant any other wishes?)

Play on, Sax Man. Play on. (At a safe distance, of course.)

So, my daughter sometimes has a smart opinion … when she has all the facts, and knows how they connect. But she also has opinions that aren’t so worthy. She’s pretty convinced that my dog’s food should be something she gets to eat. She’s fairly biased in favor of sticking her fingers inside electrical sockets. In fact, she holds these opinions so strongly, that when we try to gently point out faults in her analysis of the deliciousness of kibble or the enjoyment levels of sticking one’s fingers into wall outlets, she refuses to listen! (Rude.) She clings to her opinions even still.

All this to say: reporting and analysis matter. A lot. They’re the two crucial layers on top which worthy opinions form. I am not advocating for uninformed, incoherent shouting of ones biases … no matter how pinchable your cheeks may be.

(End of the Save-My-Butt Due to Social Media Section.)

(Panic-checks Twitter.)

Okay then: How might our example podcasts evolve at this stage of the Style Spectrum, when they contain the hosts’ and/or the teams’ points-of-view?

This is often a hidden change, something not easily surmised from the show’s name or tagline. You actually have to spend time with it to understand their POV. So here, our two example podcasts would likely keep the same names as before, just with more opinions freely shared inside

So, our coffee show’s host begins to proactively prescribe what they view as the best techniques to make coffee at home, or perhaps they begin to share their opinions on the latest coffee news or trends. (Robusta beans are on the rise, but I still think arabica are better.)

So, our coffee show’s host begins to proactively prescribe what they view as the best techniques to make coffee at home, or perhaps they begin to share their opinions on the latest coffee news or trends. (Robusta beans are on the rise, but I still think arabica are better.)

Likewise, the marketing show’s host might urge listeners to try one specific approach to marketing, rather than just objectively point out all the various ways you could succeed or all the various trends gaining popularity.

When you offer worthy opinions, you become a larger presence on the show and for your listeners. Offering your beliefs loudly and proudly is among the best ways we have as storytellers to find common bonds with others. Having a point-of-view helps you separate from all the milquetoast marketers out there.

That’s all part of a powerful recipe to cook up a community — that middle-right section of the Experience Spectrum that we failed to reach in Part 1. We can now cross the middle line and reach it:

I believe the only way to evolve a show beyond a commodity and towards something more transformative is to freely offer your own beliefs. This creates connection and shapes a community with others who share your beliefs. It also ensures you’re very FOR some people and very NOT for others. What plagues so many commodity experiences is they’re trying to appeal to too many people in loose ways, rather than bringing the right people all the way into their corner.

Stories built on a set of clear beliefs help illuminate commonalities that connect people to one another. That’s how communities form and strengthen.

🏠 Continuing our house metaphor: If soundly reported information is the foundation, and smart analysis is the scaffolding, then worthy opinions are the blueprint. What should we build? We need a point-of-view for how to build the house. But people don’t want a house. They want a home. So our jobs as builders aren’t finished yet.

A house is a physical thing. A home is an emotional one. It’s not about what was built that makes it a home but rather how they feel about it. Thus, we’ve reached the top of the Style Spectrum, where facts, analysis, and opinions give over to the most powerful thing of all: emotions.

The top tier of the Style Spectrum: inspire.

By stepping up one last tier, you create a show that does more than opine. You urge action. You spark change. You play to the head and the heart of your audience. You raise your hand and say, “This matters. This is for us. Let’s go there, together.”

By stepping up one last tier, you create a show that does more than opine. You urge action. You spark change. You play to the head and the heart of your audience. You raise your hand and say, “This matters. This is for us. Let’s go there, together.”

If the tier below this one (opine) is about adding your point-of-view, I think inspiring others also requires you to add your personality. They shouldn’t just hear your objective case for why a certain path or idea is, in your opinion, the way to go, but instead, they should feel it. It’s an emotional case, too. The way you truly feel about the subject, and about the community, and about the journey you’re on together should all come through the content in a forceful way.

Even shows that are purely entertainment-based can inspire others when the hosts freely share how they really feel about the subject being explored. I’m reminded of Binge Mode, from The Ringer, which covers high fantasy and sci-fi series like Harry Potter, Star Wars, and Game of Thrones. The hosts can often be heard getting emotional about the plot points, or laughing hysterically over a moment in the story or their own ridiculous inside jokes with their listeners. In other, more quiet moments, they also celebrate the power of stories more broadly, and why stories matter so much to them and to the entire audience.

I’m reminded also of Akimbo from Seth Godin, where yes, he talks about commerce and marketing and career growth, but he ties them back to the culture. You can sense a righteous indignation for certain parts of the current system, and a deep care for the subjects he covers. Seth covers the material and executes his work as if it’s his vocation, not just a job.

I also think about Chase Jarvis LIVE, the show from photographer and CreativeLive CEO Chase Jarvis. Yes, he’s talking about the success creative people have experienced, but there’s a certain awe and reverence he brings to the interviews, a sense of wonder at creativity in the world (and those who lead creative careers). He talks about creativity with a capital-C, found outside of the arts, affecting everything.

I think about Radiolab and The Bill Simmons Podcast — the first highly produced and heavy on sound design, the second an interview show with a single host. The team behind Radiolab and sportswriter and entrepreneur Bill Simmons constantly push their genres and their explorations of various topics forward. They’re explorers, ceaselessly curious. That comes through in the shortest question Simmons asks all the way up to months of reporting and editing immersive episodes at Radiolab.

If you can pinpoint and tap into your own emotions towards a subject and allow them to come through forcefully, coherently, and consistently, YOU will feel more inspired … and so will the audience. You don’t need to be the hosts of Binge Mode, or be Seth Godin, or be Chase Jarvis. You don’t need to cover instantly popular topics like Radiolab (science, mainly) or Bill Simmons (sports and pop culture). You can do this in your own way, with whatever emotional expressiveness suits you, with no more resources than the current time you can invest in your show. It’s not about how much time or money you spend. It’s about how you spend it that counts.

By the way, when I talk about the top tier of the Style Spectrum as being the place where you “add your personality,” I don’t mean concoct a bunch of shtick. You shouldn’t mimic the stereotypical behavior and sounds of a news anchor or somber prophet or chest-beating guru or sound effect-ridden radio show.

I mean “personality” in the more fundamental, definitional sense:

Personality: The totality of qualities and traits of character and behavior, specific to one person.

The totality of who you are. Your full self, fully present.

You aren’t sharing facts, or analysis, or opinion. When you inspire, you’re doing something much more vulnerable and much more powerful:

You’re sharing yourself.

![]()

Let’s just revisit our example shows one last time for the top tier of the Style Spectrum. It’s once again a hidden change, so the names can stay the same:

We’ve moved up one step from the opinion-driven show:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now. And here’s what people should do with gold.

We’ve now started to create a show that inspires:

🎁 I’ve collected this gold. You have some now. And here’s how you can make your life, your culture, and your world better as a result this gold. I urge you to act. Today. I can’t wait to see what you do.

The Home Barista now features a host who has a vision for what the coffee industry should be like, and a tendency to step back and marvel at the importance of coffee, and the surrounding culture, and the people involved.

Marketing Decoded would be more like a call to arms for marketers to execute the right way, with empathy for others and a long-term view. It would find a common enemy to combat, like our current journey’s attack on commodity content and marketers on auto-pilot. This show, at its more inspirational, would envision a better marketing industry for all.

That’s what inspirational shows do: They focus on and advocate for positive change. They imagine what’s possible. They’re like great keynote speeches or big idea-based books. They don’t invent radically new things. Instead, they create two very logical (but beautiful) reactions in others, the names of which I’ll just decide on when we arrive at the end of this sentence okay let’s see almost there yep I think I got it okay cool let’s go with these:

“Head-smack moments” and “chest-lightning.”

“Head-smack moments” are when something has been revealed to you that was previously buried under layers of conventional wisdom, or else you were reminded of something you once held dear but have since lost. You end up smacking your forehead going, “Of course! THIS! How could I not see?! How could I forget?!”

Often times, these moments are summarized by a single, powerful line or proverb shared by the creator. These are the “Tweetable Moments.” You can almost play Tweetable Moment Mad Libs to get what I mean:

“Don’t X because of Y. Y because of X!”

“The point isn’t to do THIS. The point is to do THAT.”

Or a real example from this really great author, public speaker, and blogger you strangely endure for a ton of words: “Stop acting like experts. Start acting like investigators.“

(Pretty much the best pithy comment ever made, I’d say, in a totally unbiased and very humble way.)

“Chest-lightning” is that feeling you get when someone is speaking to your very core and you can’t help but feel like leaping up, tossing your chair aside, and screaming, “HECK YES!” and sprinting through a brick wall. The feeling swells within you, and it crescendos to the point that you’re jolted into action.

Both head-smack moments and chest-lightning are direct results of something that inspires you — not in a fleeting way, like a coach barking at his players at the end of the game or an Instagram influencer’s latest hollow grab at attention, but in a deep, lasting way that changes you.

Just like I did with “personality,” this is another time I mean the word in a more definitional sense:

Inspire: to fill with enlivening or exalting emotion.

That’s what our two example shows do at this stage, and that’s what our shows should do, too.

I think “inspiration” gets a bad reputation as something that’s not overly practical. Someone reading this is probably thinking, “Eh, really? You had me at facts-analysis-opinions. Inspiration sounds so … squishy.”

This bad reputation was likely shaped by so many people doing such a poor job inspiring others that they create a certain skepticism or even cynicism in others — maybe in you. That form of “inspiration” is like my 17-month-old daughter’s opinions about eating dogfood or sticking her fingers into electrical outlets: Their ideas don’t really mean much because they haven’t been built on the lower layers of the Style Spectrum. People who share hollow inspiration see the work as purely the game of Tweetable Moment Mad Libs. In reality, those pithy sayings are just a brief summary, a handle to grab hold of, following all the hard work of building your ideas on facts, analysis, and opinion, before you’re able to truly inspire.

So let’s call our form of inspiration real inspiration. You, the creator, focus your work on the change you want to see in others, not the attention that comes your way. You talk openly about your vision for a world that doesn’t yet exist — but wouldn’t it be something if we achieved that someday? If you believe in this vision, join our journey to make it a reality.

In this way, real inspiration isn’t vapid or fleeting. It creates profound and lasting change in others.

That’s just about the most practical thing you can offer.

In marketing today, we have so much data to judge the demand for things, we often pander to meet what others want to hear. In doing so, we hand out commodities. But a select few marketers — perhaps you — genuinely want to inspire others. They want to share things others need to hear, regardless of existing search traffic, or whether it’s trendy to glom onto this latest trend or buzzword to seem like a leading expert.

Experiences that genuinely inspire and transform others can’t justify their existence by studying existing demand. That’s pandering to the audience. Inspiring leaders push the audience instead.

Almost no shows ascend to the top tier of the Style Spectrum. Very few experiences genuinely inspire, because very few people are comfortable being so vulnerable, so fully present, and so willing to share what others need to hear instead of want to hear.

If you want to ascend up the entire spectrum, you can’t hide behind soundly reported facts or smart analysis, or even the good intentions of worthy opinions. You’ll have to step out into the light, where everyone can see you — quirks, beliefs, emotions, and all. Audio is already an intimate medium, but to be fully present in your show like that? That’s a new level of being laid bare. There’s nowhere to hide. You’ve stuck your neck way, way out — and the rest of you too.

I’d urge you to do so, to do something that leads with emotions, with a plea for a better way. Get in touch with your childlike wonder at the world, unleash an insatiable curiosity, and cling fiercely to your optimism for what the world could be. Just know that all those things make it easy, and common, for the skeptics and the cynics to dismiss you and your work as overly naive or idealistic.

That might seem hard. At very least, it’ll be harder than churning out more commodity content. But for your organization, an inspiring, transformative experience shared with your audience is just about the most defensible, results-driven thing you can possibly do.

It’s also the most transformative thing for the people involved: for the audience, who embarks on a journey with you, and for YOU, as you’ll find and hone your voice in a visceral and enduring way. That will serve you forever, in everything you do.

Inspiring others isn’t about posting pithy sayings or moving people to tears with some sappy music. Instead, inspiring people is about showing them what’s possible, reminding them why they do what they do, or love what they love, and empowering them to go join a journey. Real inspiration requires real emotions — the full range of ‘em. The totality of your traits and characters, your personality, brought forth into the work you do.

That’s what triggers head-smack moments and chest-lightning. That’s what allows you to be fully present.

![]()

What?

Oh, thanks. I was proud of that one.

Seriously? You’re taking credit for this giant post?

…

…

…

…you’re still mad about the saxophone jokes.

Sigh.

Alright.

Fine.

Use your infinite wisdom and rhythm to bring us home, won’t you?

Remember way back at the beginning of Part 1? (So like six to eight weeks ago in reading time?) We looked at the Experience Spectrum’s left-most end, where commodities live. Remember what’s missing when we simply hand out commodity experiences to others?

The story of what could be.

It turns out that the need to share a compelling story of what could be is what both the Experience Spectrum and Style Spectrum share. To max out on either spectrum, we can focus on continually improving the story of what could be.

Bob, if you can be so kind as to put the two together?

Thank you, Bob. So … along the Experience Spectrum, the story of what could be is experienced by the audience like a journey towards a distant mountain peak. The community embarks on a quest, meeting other communities and individuals, adding new members to the adventuring party, and continuing deeper into the unknown jungle in pursuit of something, together.

Along the Style Spectrum, the story of what could be is delivered by the creator as real inspiration. We become fully present in the work — not in some vapid, Instagrammable sense, but in a practical, strategic sense, as you proactively style your show to maximize your presence and share your personality.

In putting both spectra together, we can try to place our own shows onto the matrix shown above, thus getting a better sense for how we might improve — all in the name of making someone’s favorite show. (We’ll focus on placing various shows onto the matrix next time. We’ll also add a third dimension which is still missing from the matrix.)

(By the way, while I have you inside some parentheses already: I recently learned that the plural of spectrum is spectra thanks to MSR’s managing editor Molly Donovan, so now I’ll be finding every excuse to use the word in future posts. Because what a word. Also, it kinda sounds like a superhero nickname, and I’m already on the record pushing you to become a friggin’ podcasting superhero. Spectra! The Maximizer of the Two Spectra Necessary to Make Great Podcasts!)

(We’ll workshop it.)

My point is … I’m obsessed with the Avengers — AND ALSO — the most beloved podcast we can possibly create derives its value from the most beloved story of what could be for our specific audiences. That should be our focus. Want to improve the show? Revisit the story you’re telling. But too often, we try to improve the raw asset. We think we need a better process for capturing news stories, or more famous guests, or more clever ways to promote the show, or of course, better hardware and software and YOU GUYS! Let’s build ourselves a STUDIO IN THE OFFICE!

It’s all just the act of dressing up a commodity.

What if we revisited the thing that actually creates value, that actually inspires and takes people on a proprietary journey? What if we spent more time on the thing that prevents us from ever being a commodity in the first place? The story of what could be!

For shows that maximize both spectra (+5 points), that story isn’t just a slogan or case study or benefits statement wrapped around or slapped on after the fact. (“We really just sell the same crap as everyone else, but we make it sound better.”) No, this isn’t about bait-and-switch marketing or vapid inspiration or a sexier-sounding name and tagline for the podcast. This is about real inspiration — head-smack moments and chest-lightning that sparks action and lasting change.

The story of what could be can be so powerful, so compelling, that experiencing it is the entire goal. Maybe then our audience would invest significant time with us, which then could earn trust and love, which then gives us the best shot at our ultimate aim: being their favorite show.

Soundly reported information can’t do that. Reporting is about gathering the facts — a valuable foundation, but insufficient to build the house.

Smart analysis can’t do that. Analysis is about connecting facts to reveal the broader context — important scaffolding, but not itself the house.

Worthy opinions also don’t focus enough on the story of what could be, either. Opinions are about handing others blueprints — your singular interpretation of what the house should be.

But inspiration? Real inspiration? That’s the difference between building others a house and creating a home. It’s a feeling you instill, not a fact or opinion you hand out. Real inspiration fills others with enlivening or exalting emotion.

What can they do with that? Anything they damn well choose. They’re inspired to act, to participate, to change themselves and others around them. You aren’t their leader so much as their cheerleader. Together, you’re a group of equal participants on a transformational journey.

In this way, you no longer tell them, “I have an opinion of what this should be.” It’s more inviting than that. It’s like saying, “I believe that this is what could be. Do you see it? Here, let me show you. Do you agree with me? Let’s discuss. Do you want to go this way or that way? I don’t know how, either. Here’s the mountain peak we agree would be awesome to reach. Here are some tools I can share with you — a compass, a backpack, some supplies, some boots. Here’s some progress we’ve already made hacking away in this jungle and, oh right, here’s your machete so you can start hacking away with us. I’ll keep going to the left. You can come that way and help me, or you can go a different way and report back. All that matters is we figure out a way forward. Together.”

That’s far more inspiring. It’s also a whole heck of a lot messier than a neatly packaged list of steps or a hastily posted opinion. It’s hard to bottle up anything transformative into a single tweet, or blog post, or a PDF guide. (The point isn’t the key takeaways, remember. This isn’t a transaction.) It’s easier to give prescriptions in the form of opinions, rather than instill change in the form of inspiration. Inspiration is messier. Emotions are messier.

That’s the beauty of making a show. Shows gleefully explore the mess while other things oversimplify things to a frustrating degree.

To do that, we can use our solution to pike syndrome: stop acting like an expert and start acting like an investigator. Inspiring others doesn’t mean handing out all the right answers. It means asking better questions. It means going deeper in a world trending more shallow. Investigators willingly embrace the mess, admit they don’t have “the” answers, and proceed with figuring it out anyway.

Your audience can’t answer the questions that matter most through a quick google search all by themselves. They can’t just find and ask an expert and be done with it, either. Even connecting with a community group isn’t enough. That group needs to embark on a quest to solve tougher problems or understand things more deeply or create more profound change, together.

When you inspire others, you become fully present, while others experience your work like a journey that’s wholly proprietary. It can’t be duplicated anywhere else — most notably because you aren’t present anywhere else. When you reach the top of the Style Spectrum, you’ll start using your unfair advantage to its fullest extent.

Don’t hand out commodities. Instead, make something proprietary.

Don’t remove yourself from the work. Add more of who you are, until there’s nothing left to give.

Invite them on a journey, and spark meaningful action and lasting change by telling the best possible story:

The story of what could be.

Next week: We’ll put it all together.

Go back and read Part 1 if you haven’t or you need a refresher. Next week is our third and final mega-post.

![]()

Go to Part 3: The Fortress of Favoritism ➡️

Be sure to subscribe to get each of these new ideas — plus a video from me found nowhere else — every Friday morning via email. Join thousands of subscribers from brands ranging from Red Bull, Adobe, Amazon Prime Video, Mailchimp, and Salesforce, to thousands of small businesses, startups, and creators. Join the journey at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com