Transactional Shows: Why Marketers Fail to Make Anyone’s Favorite Podcast

This article is part of a weekly exploration to answer one question: What would it take to make your audience’s favorite podcast? Each entry in this series builds on past ideas. It will culminate in the first session of our online, interactive, cohort-based workshop for marketers, where we do real work on our real podcasts, together, to find and share our voices and make a difference for our audiences.

Subscribe via email to get each entry in this exploration, plus early access to our first workshop sessions and other creative experiments. (If you’re already a subscriber to MSR Monthly, you will need to join this list separately. Visit marketingshowrunners.com/favorite to subscribe.)

* * *

“We love them, but we could never be them.”

I’ve heard some flavor of this idea from way, way too many marketers over the years. We get inspired by something, like our favorite podcast, and then we immediately think about all the things we couldn’t do on our version of that thing, like our own show. In other words, when we feel most inspired is when we should try to deconstruct and diagnose and dig deeper to learn … but it’s also when we disassociate ourselves from our inspirations.

“It’d be great, but…”

“They’re in one situation, and we’re…”

“We don’t have…”

“We can’t possibly…”

“…so let’s not even try.”

Today, we push forward by looking harder at this issue. Why aren’t we creating our audience’s favorite podcasts? Why can’t we? Also: Can’t we? Who’s to say that just because “we’re marketers,” we are unable to achieve this lofty but worthy aim?

The feeling we get from our favorite shows is the very same feeling we can instill in others with the episodes we create. We just need to reframe our thinking — not about resources, not about production techniques, not about our industry or our topics, but about something much more vital to the success of a show: the type of value bottled up inside it.

Continuing Our Journey: What Does It Take to Create Their Favorite Podcast?

In my last entry in this exploratory series, we talked about the true aim of any marketer: earn trust and love. But to do that, we need to do something hard: earn their time investment. Trust and love develop over time. But to do that, we need to do something hard: create something worthy of choosing. In a world of infinite choice, people choose to spend time only with the things that are among their favorites. When you have options, you can constantly upgrade for any one specific purpose, medium, topic, or any number of attributions (or combinations of them) until you arrive at the one that is your personal and preferred pick for a specific purpose.

Our podcast must become their personal and preferred pick for a specific purpose. In other words, for that specific purpose, our podcast must become their favorite.

In that last article, as we traipsed around the world of psychology and marketing, we realized that “favorite” doesn’t mean “great.” It doesn’t mean mimicking our inspirational heroes’ production techniques or seemingly endless resources. “Favorite” is a personal thing, like your favorite restaurant, or shirt, or coffee mug. Your favorite things are just that — your favorite things, regardless of the “soundness” or quality in any academic sense. You may even freely admit that your favorite restaurant isn’t the best restaurant, or your favorite clothing brand, or your favorite show. But it is your favorite, and for a very simple fact: it’s personal.

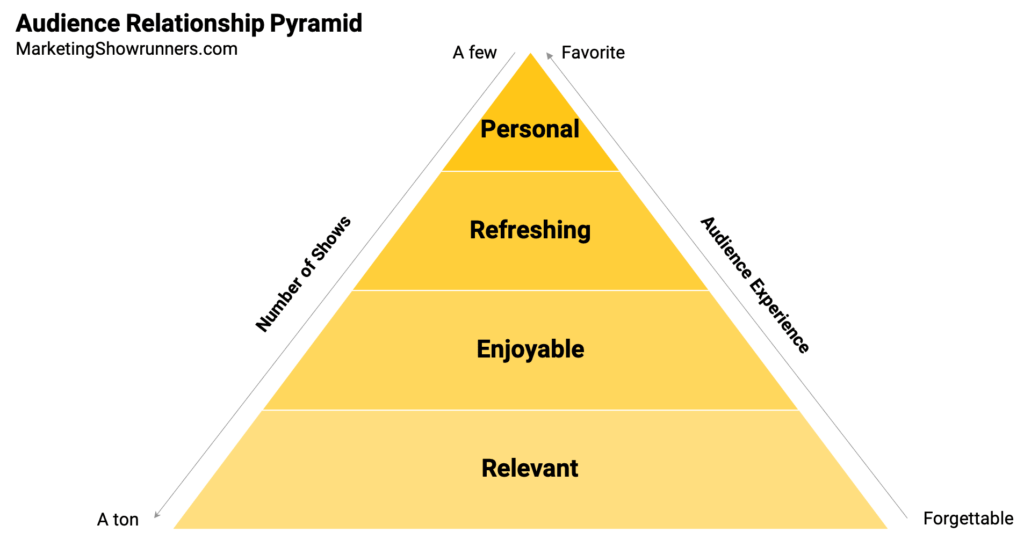

So, let’s recap quickly. If the job is to earn the trust and love of others through your show, you should focus on making their favorite show. If the job is to make their favorite show, you need to make the show personal. Being relevant won’t suffice. Being entertaining won’t suffice. Even being a welcome sort of different (what I call “refreshing”) isn’t enough. We have to tap the emotional reasons people feel personally tied to the work they do or the themes we explore. We have to make the show feel personal to the right audience.

We concluded our last step in this journey by visualizing this change in our focus through a diagram called the Audience Relationship Pyramid:

So, now what? Where does this leave us? If we agree to these ideas so far, then how do we actually execute? How do we create a show that feels personal, that stands a chance of ascending the Audience Relationship Pyramid?

How do we create their favorite show?

Well, we can start by taking a look at the types of shows we typically build, diagnose any underlying issues, and work our way out together. Let’s set aside any preconceived notions we may have and try to approach this with some blank canvas thinking, reach first principles, and re-engineer how we operate.

Ready? Here goes…

How Marketers Typically Approach Their Podcasts

In their shows, most marketers provide transactional value. In doing so, they create a transactional show.

Transactional value is a type of education and/or entertainment that people seek in reaction to a problem they’re trying to solve as quickly as possible. Maybe they want to learn how to do something for work, or maybe they’re bored waiting in line and just want a distraction to fill the time.

Transactional value and, therefore transactional shows, can absolutely be helpful, but the value tends to be rather fleeting. It only applies at this moment or for this situation. It provides little to no ongoing, evergreen value.

In addition to its use case being fleeting, a transactional show tends to be forgettable. It can be easily replaced with the next stimulus or distraction, or perhaps the better-advertised version of itself from a competitive source. It’s a commodity. Think of a podcast that teaches practical steps to do a certain type of job by interviewing experts, or a show that curates a list of news items and presents them without analysis or opinion. These are transactional shows. These are commodities. Transactional shows face a few problems as a result.

First, they’re easy to create, and so a lot of people create them. Because of that steep competition, any potential resources you may have saved when making the show must now be spent tenfold just to cut through the noise when you promote the show. (Turns out it’s far easier to cut through the noise by making something a little bit different in the first place than by promoting something a lot more loudly after the fact.)

Second, transactional shows often focus their topics and content on capturing existing demand. They justify what they address or create by looking at things like search traffic. Again, this means a lot of others also create this type of content, because it feels safer, and because the ideas are handed to them. It takes very little thought to see that everyone is searching “best podcast microphone.” Naturally, you create content to answer that question — but then you face the same problem as the first issue above.

Lastly, and perhaps most worrisome of all, transactional shows are not overly dependent upon the creator’s unique point of view. Anyone could host this show. Anyone could deliver this value. So who cares if it comes from you? Certainly, the audience doesn’t care. The point of a transactional show is just that: the transaction. They’d rather download the information straight to the brain than endure the experience. In other words, if they can get it somewhere else in a way that seems quicker and with less time invested, they will. They’d rather skip the experience itself, because the experience itself isn’t the point. Ending the transaction is.

I don’t want to spend time learning how to do something. I’d rather just be good at it already. Skip the experience and just finish the transaction already, please.

This is not the way to earn trust and love. This is not the way to create their favorite show.

Categories of Transactional Shows

It’s important that we learn to spot whether our show is transactional or not. I’ve identified three major categories — but feel free to share your own.

The “We Also Have a Podcast” Podcast

These types of shows are a sign that a team is just glomming onto a trend. They prioritize optics and tactics over strategy and service. As a result, they make an “audio blog,” an afterthought show that would be far better shipped as a series of articles to skim than an immersive audio experience into which people choose to invest 10, 20, 40, or 60 minutes a week, or hours per month. One sign you might be creating a “We Also Have a Podcast” Podcast? Your audience keeps asking for transcriptions of the episodes, so they can scan them more quickly.

While there are some less frequent but helpful use cases for transcriptions (SEO, accessibility, superfans referring back to the goodness inside an episode), when it becomes a pattern, it’s a sign you’re not maximizing the medium of audio, nor are you strategic enough about why you’re using audio versus text.

(This type of show plagues many B2B brands specifically, as you could remove the names of many of those shows and just call them all the same thing: “Talking Topics with Experts.”)

The “We Also Have a Podcast” Podcast is a commodity that blends in, and because it’s not defensible, marketers are often forced to position this type of show as somehow “better” than others. They use subjective words (like better, or deeper, or more X, Y, or Z) to convey the value to listeners, instead of an objective description of the show, which should naturally reveal its value and differentiation.

If you say things like “we talk to marketing experts but go deeper than other shows,” it means you might be running a “We Also Have a Podcast” Podcast. But if you can instead say “we talk to marketing experts but ask them to take us through one crazy experiment they ran,” you might have something proprietary.

In the end, the “We Also Have a Podcast” Podcast anchors us to the trend or the competition, not the audience’s needs. We’re forced to describe it in contrast to other shows. A show that inspires trust and love can stand on its own description — which should light audiences up and inspire them to select it.

The “Wheel of Fortune of Fortune 500s”

In this category of transactional shows, a team takes what is ultimately a commodity podcast or idea, then adds a gimmick unrelated to the brand or topic — like, for instance, adding a literal spinning wheel to decide on the questions or categories when you talk to Fortune 500 executives. Or imagine another scenario that is less obviously gimmicky: a “rants” section at the end of your podcast, where you snark about a few news items in your industry.

Yes, in general, that might improve the entertainment value. But in reality, does it match your overall brand in tone? Does it match who you are as a person? Why not use the opportunity to say something meaningful, something that relates to the themes you want to own as a brand in the market, and the problems you want to solve or feelings you want to instill in your audience, rather than haphazardly apply a cheap gimmick? We don’t operate in a generality, so ditch the things that work “in general,” revisit your specific reality as an organization and as a service-minded marketer for your audience, and craft little moments, sections, or gimmicks that relate.

Shows don’t need to use gimmicks to fall within the “Wheel of Fortune of Fortune 500s” category. . Often, they just use a clever name, or maybe a bombastic one (“F*ck Sales: The Hardest-Hitting Podcast on Sales Ever!”). You think, “Wow, that’s a great name,” before hearing an experience that is ultimately the same as every other show. Regardless, this category has the same problem as the first one: We’re not saying anything truly different or meaningful.

The show itself is still really just the same show as everyone else. It’s bland, but the marketers behind it tried to drizzle some chocolate on top.

The “Amtrak Airlines”

This final category of transactional shows has nothing to do with the creative and everything to do with decision-makers who don’t understand what a show is good for.

Maybe the host launched a podcast as a personal side project within the business because they wanted quick fame. Maybe the CMO who greenlit the show expects broad reach. Either way, it ignores what a show is good for: affinity, not awareness; deep resonance and community, not huge reach and traffic.

This is like building a train, which is great at doing many train things, but then expecting that train to fly. Why not acknowledge that we are building a train, and focus on making the best damn train possible?

With this category of podcasts, showrunners might get frustrated, because they’re trying to run Amtrak as best as they can, but their boss or team wishes they were building Amtrak Airlines.

These types of shows — and the marketers behind them — are forced to focus on total downloads, the speed at which the downloads increase, the fame of each guest they book (better be bigger than the last one!), and other vanity ideas and metrics. Rarely if ever does the team focus on the actual value of the show to the brand, or the way it helps the audience in deeper ways than other, more shallow content. Rarely if ever are these teams focused on earning trust and love.

If you think you might be creating a transactional show, don’t fret. You’re making a podcast and doing so because you genuinely want to create your audience’s favorite show. You’re on the right path. You’re just heading in the wrong direction: transactional value.

In my next entry in this ongoing exploration, we’ll turn around and face the other way. We’ll turn our backs on transactional podcasts and focus on the shows that are capable of becoming their favorite: transformational experiences.

Join the journey to understand what it takes to make their favorite podcast:

Subscribe at marketingshowrunners.com/favorite to get the next entry the moment it’s live, plus early access to new initiatives, like the project that culminates this exploration: a cohort-based, online, interactive workshop doing real work on our real podcasts, together. Subscribe >>

Or you can get our monthly roundup of our best content using the box below. Thanks for reading!

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com